A Man Who Keeps Up with the Times

[2 items]

A MAN WHO KEEPS UP WITH THE TIMES

"I'm simply fascinated by madness. It's a good thing to dismiss everything at once, isn't it? Everyone finds something interesting in a crazy family. Everyone says, 'Oh yes, my family is completely insane.' Mine really is. I'm not joking, boys...

---

I love shock tactics. I want to deceive and get a reaction. There's nothing artistic here, but at the very least, it's astonishing. Moms and dads think I'm somewhat mysterious, but I'm not an innovator. Actually, I'm revealing what was already inside. I'm just reflecting what's happening around me. But not all of my experiences are pleasant. Some even I find disgusting and dangerous. But when I'm told that I'm a bad influence on youth, I just laugh. I'm not a very responsible person.

---

I'm a pretty ice cube. Very cold. That's what I think. I have a strong lyrical, emotional drive, and I don't know where it comes from. I'm not sure that everything in my songs passes through me... I can't feel strongly. I'm numb with cold. So in some sense, I'm an ice seller.

---

I've never loved. Once I fell in love, and it was terrible. It killed me, dried me up and became a catastrophe. There was hatred in it. Being in love is something that breeds animal passion and rage. It's a bit like Christianity or any other religion.

---

When I was 14, sex unexpectedly became the most important thing. It didn't matter at all who or what provoked it, how long it lasted. It could be a cute boy from another school or someone else I brought home. That was it. My first thought: if I ever end up in prison, I'll know how to stay happy.

---

I remember how it happened for the first time. Once I was being interviewed and was asked if I had anything fun in this area. I said, 'Yes, I'm bisexual.' This guy, the journalist, never understood what I meant. He gave me a frightening look: 'Oh Lord... Both rooster and hen...' I didn't think my sexual life problems would be so widely covered by the press. After all, it's something like notes on cuffs...

---

When I brought the film 'The Man Who Sold the World' to America, I dressed in women's clothing. Because I was going to Texas. One guy there saw me, grabbed a gun, and called me a faggot.

But the dress was wonderful anyway.

---

...I will perform alone, and nothing will stop me. Because people's desire for scandal gives me a chance. Newspapers have written volumes about how I'm sick, how I've killed truthful art. And if they could, they would give everything to real artists. This is very nice, because they've spilled heaps of blood describing the latest color of my hair. I would like to know why they waste time describing my poses and clothes. Why? What for? Because I'm dangerous.

---

I've already lived through the time of my rise. About 50 percent of it was pleasant. I now only remember the time when I went to Japan. There are absolutely charming boys there. Well, not exactly boys. They're 18-19 years old. They have a delightful way of thinking. They bloom until 25, then unexpectedly turn into samurai, get married and have a hundred children. I really like that."

Translated from English by L. Melnikova ("Rodnik," 1989)

Prepared by Roma S.

---

---

The terrifying freak "Elephant Man." An English officer captured by the Japanese. An alien from space. A hereditary German military man who became unemployed after World War I and lost everything except his faith in Germany.

A two-hundred-year-old man. An underground bard. Some mutant that emerged as a result of nuclear apocalypse. The wizard Jareth, king of goblins. A fit, surprisingly youthful gentleman... And all this is one person.

We're not talking about an actor, although this person did appear in films. And most importantly, hardly any movie star felt so natural in such different roles as the one we're discussing, and hardly anyone was so identified in the public consciousness with their roles, at least with such a multitude of roles.

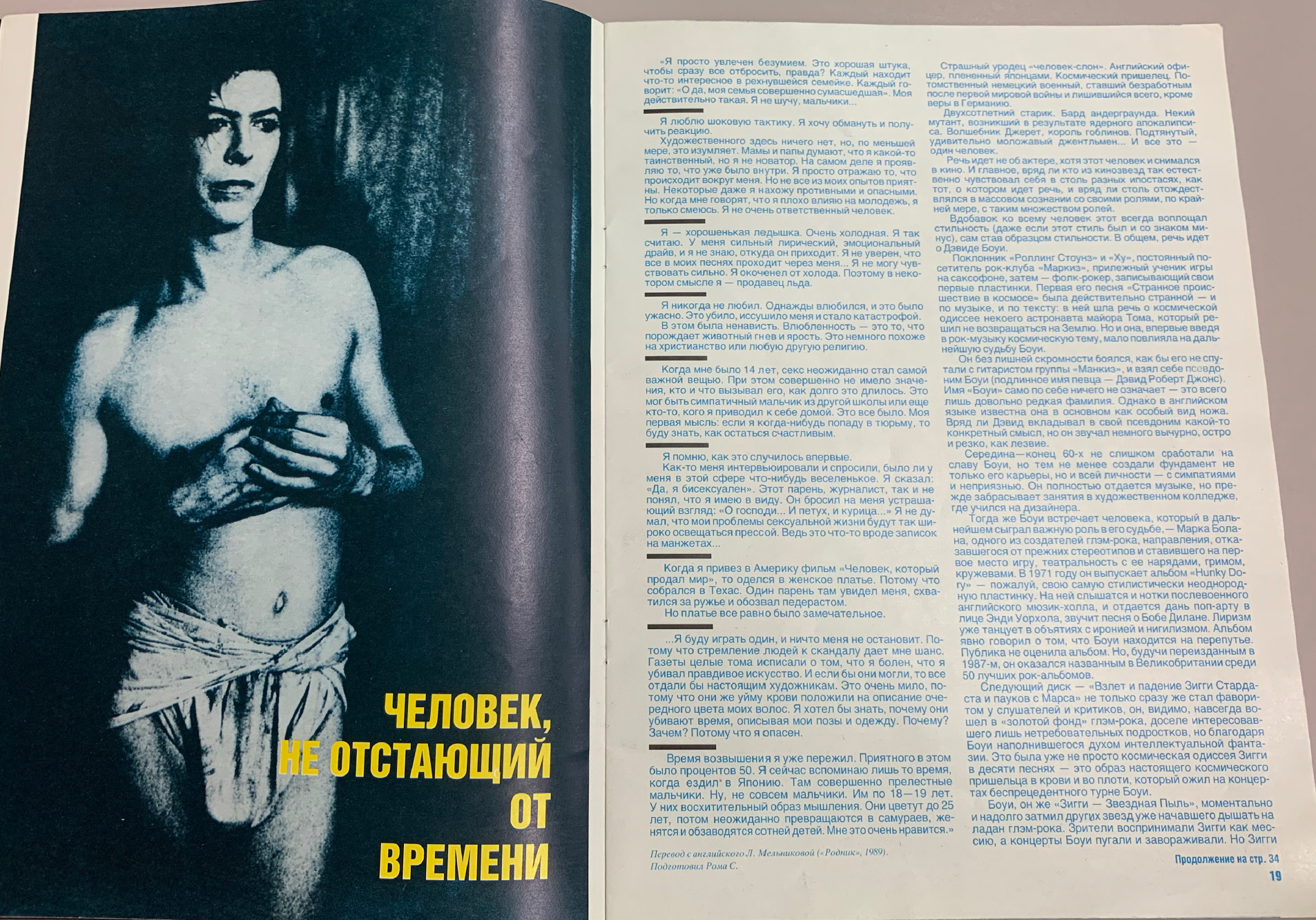

In addition to everything else, this person has always embodied stylishness (even if this style was sometimes negative), himself becoming a model of style. In general, we're talking about David Bowie.

A fan of the Rolling Stones and The Who, a regular visitor to the rock club "Marquee," a diligent student of saxophone, then a folk-rocker recording his first records. His first song, "Space Oddity," was indeed odd—both in music and lyrics: it told about the space odyssey of a certain astronaut Major Tom who decided not to return to Earth. But even this song, which first introduced the cosmic theme into rock music, did little to advance Bowie's fame.

Without unnecessary modesty, he was afraid of being confused with the guitarist of the Monkees, and took the pseudonym Bowie (the singer's real name is David Robert Jones). The name "Bowie" doesn't mean anything in itself—it's just a rather rare surname. However, in English it's known mainly as a special type of knife. It's unlikely that David put any specific meaning into his pseudonym, but it sounded a bit pretentious, sharp and cutting, like blades.

The mid-to-late 60s didn't really work for Bowie's fame, but nonetheless created the foundation not only for his career but for his entire personality—with its sympathies and antipathies. He completely devoted himself to music, but first dropped out of art college, where he was studying to be a designer.

At that time, Bowie met a person who later played an important role in his fate—Marc Bolan, one of the creators of glam rock, a direction that rejected previous stereotypes and put play and theatricality with its costumes, makeup, and lace in the foreground. In 1971, he released the album "Hunky Dory"—perhaps his most stylistically heterogeneous record. On it, you can hear notes of post-war English music hall, and tribute is paid to pop art in the person of Andy Warhol, with a song about Bob Dylan. Lyricism already dances in the embrace of irony and nihilism. The album clearly indicated that Bowie was at a crossroads. The public didn't appreciate the album. But, being reissued in 1987, it was named among the 50 best rock albums in Great Britain.

The next disc—"The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars"—not only immediately became a favorite with listeners and critics, it apparently forever entered the "golden fund" of glam rock, which until then interested only undemanding teenagers, but thanks to Bowie was filled with the spirit of intellectual fantasy. This was no longer just Ziggy's cosmic odyssey in ten songs—it was the image of a real space alien in blood and flesh, who came alive at the concerts of Bowie's unprecedented tour.

Bowie, aka "Ziggy Stardust," instantly and for a long time overshadowed other stars of glam rock, which was already beginning to breathe its last. Viewers perceived Ziggy as a messiah, and Bowie's concerts frightened and fascinated.

But Ziggy turned out to be just the first in a whole series of image-masks—Bowie's transformations, which for a long time pushed aside and generally replaced the image of the singer himself. Ziggy's heir—Aladdin Sane—emerged, equally bisexual, but more refined and grotesque. A certain mutant who appeared after a nuclear catastrophe—Halloween Jack, an almost incorporeal and incomprehensibly appeared being, the Thin White Duke... Characters were born one after another from record to record and took flesh during tours...

In 1975, three years before the whole world was seized by "disco" fever, Bowie released the album "Young Americans," maintained almost entirely in the disco style. The song "Fame," composed and recorded with John Lennon, turned out to be his first single to take first place in the hit parade. But even this purely external tribute to frivolity turned out to be short-lived. The next album—"Station to Station," whose protagonist was the Thin White Duke, according to Bowie, was "a cheerful hymn to nihilism." The record, recognized by some critics as one of his most interesting works, was also one of the darkest.

The last three years of the 70s, Bowie was not only far from the feerie stage acts, but also from his previous music. Secluded with former Roxy Music member Brian Eno, Bowie experimented in search of a new sound. Eno was accused of drawing highly commercial musicians (besides Bowie, David Byrne from Talking Heads also became a "novice of his monastery") into the barrenness of avant-garde music. All three albums of those years—"Low," "Heroes," "Lodger"—were in no comparison in popularity with the public with records of an earlier period, but opened new musical ranges and themes.

Bowie's 1980 record "Scary Monsters," recorded with Robert Fripp (an acquisition thanks to friendship with Eno?), was a brilliant work in all respects—no wonder Newsweek magazine in its review, despite a whole decade ahead, was not afraid to call it "the masterpiece of the 80s." The song "Ashes to Ashes" brings back pictures of the past, revives Major Tom, "who turned into a drug addict," and reveals Bowie's unprecedented lyrical power, detached, clad in surrealism armor, cold, but hitting hard.

After three years of silence—in 1983, a new record "Let's Dance." This work is a fusion of all the rhythms and melodies that Bowie performed at one time. But it's also a fusion of experiences he went through, a synthesis of themes he exploited, reflecting his audience's fear of the future, and now also an expression of unprecedented optimism. "Let's Dance" and Bowie's subsequent tour became the sensation of 1983.

When Bowie, like many of his colleagues in the 60s, was an underground bard, he was booed by "skinheads" for his "Dylan-esque" appearance. It seems he remembered this for a long time, as he began to look for something strong, active as opposed to the non-resistant culture of hippies. Not being a superman, he found his strength in coldness and detachment.

In one of his first interviews as a superstar, David concluded: "Now I know how to be happy when I'm in prison." And before that, he told a story about how he allegedly seduced his classmate while still in school. Bowie's nonbinary heroes of that time seemed to visibly confirm the singer's inclinations. But it seems that the key to understanding such statements Bowie himself gave in the title of one of his first discs—"The Man Who Sold the World": unprincipledness. For the sake of épatage. Bowie himself soon disavowed everything he said in "that" interview, explaining it approximately like this: "I needed to say something!" The subsequent diversity of "aliens" he created also initially looked like a certain mockery of public opinion and shocked the public—however, until the time when they came into fashion...

In his changing styles and views, Bowie united Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp, teenage glam rock and the "new wave," Dadaism and avant-garde, and ultimately the romantic mysticism of hippies and the philosophy of yuppies—the offspring of the last decade—young urban professional employees thinking about careers and the beautiful life they provide. At the same time, Bowie's own style has many parallels, most of which emerged... not without his influence. He has more partners in collaborative creativity than anyone else: John Lennon and Marc Bolan, Tina Turner and Pat Metheny, Giorgio Moroder, Mick Jagger and Queen... Despite the fact that he stated that "rock and roll is dead" and "committed suicide," Bowie paved the way for musical styles, several steps ahead of fashion. Working as a producer, he became a forerunner of punk, and, fertilizing the weak viability of this style with his own creativity, opened the way for the "new wave."

Therefore, he also has many followers, and those to whom he gave a "ticket to life" as a producer: Billy Idol, Iggy Pop, Peter Murphy from the group "Bauhaus," repeating even his facial expressions and gestures, Lou Reed and "Mott the Hoople".... Bowie's friend and one of his producers, Tony Visconti, noted: "David passionately and intensely spends time with those he loves, and tries to take note of everything. When he gets everything he wants, and things come to the point of stagnation, he moves forward."

The images he created attracted the attention of artists, designers, fashion designers. He managed to grasp what was sure to become fashionable, and the newspaper "Village Voice" not without irony wrote that "one of Bowie's greatest merits is that he inspired many people to become hairdressers."

Having repeatedly signed the sentence of fashion, Bowie always remained its protagonist, exactly one step ahead of this fashion itself. It's no coincidence that he appears on the pages of such a solid publication as "The History of Hollywood Costume."

But about cinema—a special conversation. I won't say that he's a great film actor, although his role in the film "Just a Gigolo" is undoubtedly a success, and he looks good even next to Marlene Dietrich and Kurt Jurgens. In "The Hunger," his partner is Catherine Deneuve, about whom you also can't say that she "outshines" him. I won't take the 50s reminiscence "Absolute Beginners" or the children's "Labyrinth"—the roles there are either simple or close to Bowie, because he plays almost himself. We can talk about David Bowie's peculiar theater, and not only referring to his participation in the Broadway production of "The Elephant Man" or the television play "Baal" by Bertolt Brecht. Although his participation in the latter work was hardly accidental: something internal, embedded or developed by Kemp, connects Bowie with Brecht. Kate Bush, one of the most interesting contemporary English singers, known for theatrical performances (she also studied with Kemp at one time!), names Brecht, Kurt Weill with his musical theater, and... David Bowie as her main inspirers.

Bowie's inclination towards cinematography and theatricality of performance of all his acts is clearly manifested in his twenty-minute clip "Blue Jean," where he simultaneously appears in two roles. Some tend to explain such a split on screen by the split personality of Bowie himself, constantly changing his styles and appearances, completely, it would seem, identifying himself with them. Rock criticism at times completely denied his integrity of nature, preferring to see in him only a chameleon, busy hiding his essence behind masks: in the early 70s, he even gave interviews as if from a "third person"—on behalf of Ziggy Stardust. But Japanese film director Nagisa Oshima chose him to play the lead role in his film "Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence" precisely because he saw in him what others refused to see.

By the way, after "Baal," this is the first role that Bowie himself liked. Unlike the alien in "The Man Who Fell to Earth," the two-hundred-year-old man in "The Hunger," the hideous freak in "The Elephant Man," Celliers' image doesn't overshadow David Bowie's own image, and for him, it seems, this is very important.

"I like my age, 36 years. And the sensations that come with it. I feel changes happening in me—both physical and spiritual. I'm beginning to understand the charm of growing up..." Bowie said in one of his interviews in 1983. The fact is that, having created and changed many styles, he didn't fall apart, but remained himself, preserving his style and embodying it in a way of life.

They tell a story, similar to an anecdote, about how Bowie was traveling through the USSR on the Trans-Siberian Express. In Japan, from where he was returning, he bought a beautiful kimono and decided to go to the dining car wearing it. The waitress indifferently dismissed him—we don't serve people in robes, she said. Then David returned to his compartment and changed—a tailcoat, luxurious shirt, diamond brooch. When he sat down at the table again, across from him sat a man in pajamas... This case says much more not about our railways (everything is clear with them), but about Bowie himself.

Bowie's ex-wife Angie has repeatedly given interviews that could cast a shadow on David. It's hard to say how much truth there is in her revelations. But it seems they're more just calculated for scandal, like her own revelations already before the camera. For Bowie himself, no scandal can change anything anymore—take away or add.

Cinema. Records. Mime. Broadway stage. Video clips. Painting. Bowie engages in all of this, throwing himself in so many different directions that he resembles a compass needle, freely spinning in search of magnetic north. It's amazing how often he finds it and how, when the needle stands in the right position, he manages to bring several directions together. "David is truly a living Renaissance figure..." said Nicolas Roeg, director of "The Man Who Fell to Earth."

He is talented, calm, and liberated. He has already done everything he could and couldn't to move fashion forward, and now he can calmly appear in any society in any of his roles. He tours with his band "Tin Machine" and appears at prestigious collective rock concerts as a superstar. He comes to Cannes for the film festival as a worthy member of the cinematographers' brotherhood. Nearby, in Monaco, in the company of the local royal family—he is simply a member of international high society. And in Australia, he feels like an ordinary Australian, dividing life into two parts—in the soul and in a modern big city.

Once criticizing intellectualism and thorough education in his interviews, he didn't hesitate to send his son Zowie to Gordonstown in northern Scotland so that he could continue his education at the college, famous for the fact that the Prince of Wales studied there surrounded by the cult of rigid British discipline...

Bowie has a permanent residence in the Swiss Alps. They say this villa-fortress is impregnable, but he rarely stays there. If in the first half of the 80s it was easier to find him in Australia, now he is more attached to New York, where his office is located and where the threads of almost all his affairs converge.

A characteristic detail that many have already noticed: Bowie never takes off his watch during concerts. This is also an element of his style. But maybe that's why he never falls behind the times?

Nikita KRIVTSOV

This piece on David Bowie as a highly influential and openly bisexual cultural figure, largely or completely translated from an English-language source published in 1989, appears here in an issue of the glossy color magazine Mal’chishnik (Stag Party). This publication interspersed homoerotic photography with pop-culture and lifestyle pieces, borrowing—like many aspects of post-Soviet LGBT culture of the time—from Western exemplars by calquing American publications like Out (itself only in print since 1992).

This feature article was likely chosen for its casual mention of indulgence in homosexual activity by a powerful cultural figure whose persona (and, seemingly, private life) was predominantly heterosexual. As sociologist Laurie Essig has observed, LGBTQ populations in Russia differed from their Western counterparts in that they distinguished between sexual behavior and sexual identity. In this framing, homosexual behaviors are experiences rather than inherent features of personality. To a broad segment of the Russian audience, Bowie’s casual acknowledgements of his gay experiences were compelling because they held out the promise of engaging in homosexual acts without compromising a masculine or even heterosexual identity—and without endangering a public, image-based career that included the performance of masculinity.

Bowie’s reference to homosexuality in prison life—his statement that, given his ability to enjoy sex with men, he would be able to make the best of a hypothetical prison stint—may have resonated with readers familiar with the Russian penal system. In Russian corrective institutions, many inmates engaged in homosexual behavior without compromising their social status or masculine identities. A subset of inmates, meanwhile, were severely and irreparably stigmatized as a result of these encounters. These men were ostracized, relegated to the lowest rungs of social hierarchy, and victimized by abuse that penal-system administrators left unpunished, or, worse, encouraged.

The English-language piece on Bowie from which this publication derives dates to 1989, a moment when Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost was lifting taboos in many of areas of Russian life. Despite this new openness, the widespread homosexual activity within the Soviet penal system could not be verbalized. It remained especially taboo in the media. This artifact offers an example of a Soviet convention of compartmentalizing certain phenomena outside of public, and often even social or private, speech, a system of institutionalized psychological and social duplicity that Russian sociologist Yuri Levada termed “doublethink”—a term borrowed from George Orwell’s 1948 dystopian classic Nineteen Eighty-Four.