Filed Under: Print > Journalism > An “initiative group survey” from the Leningrad Rock Club

An “initiative group survey” from the Leningrad Rock Club

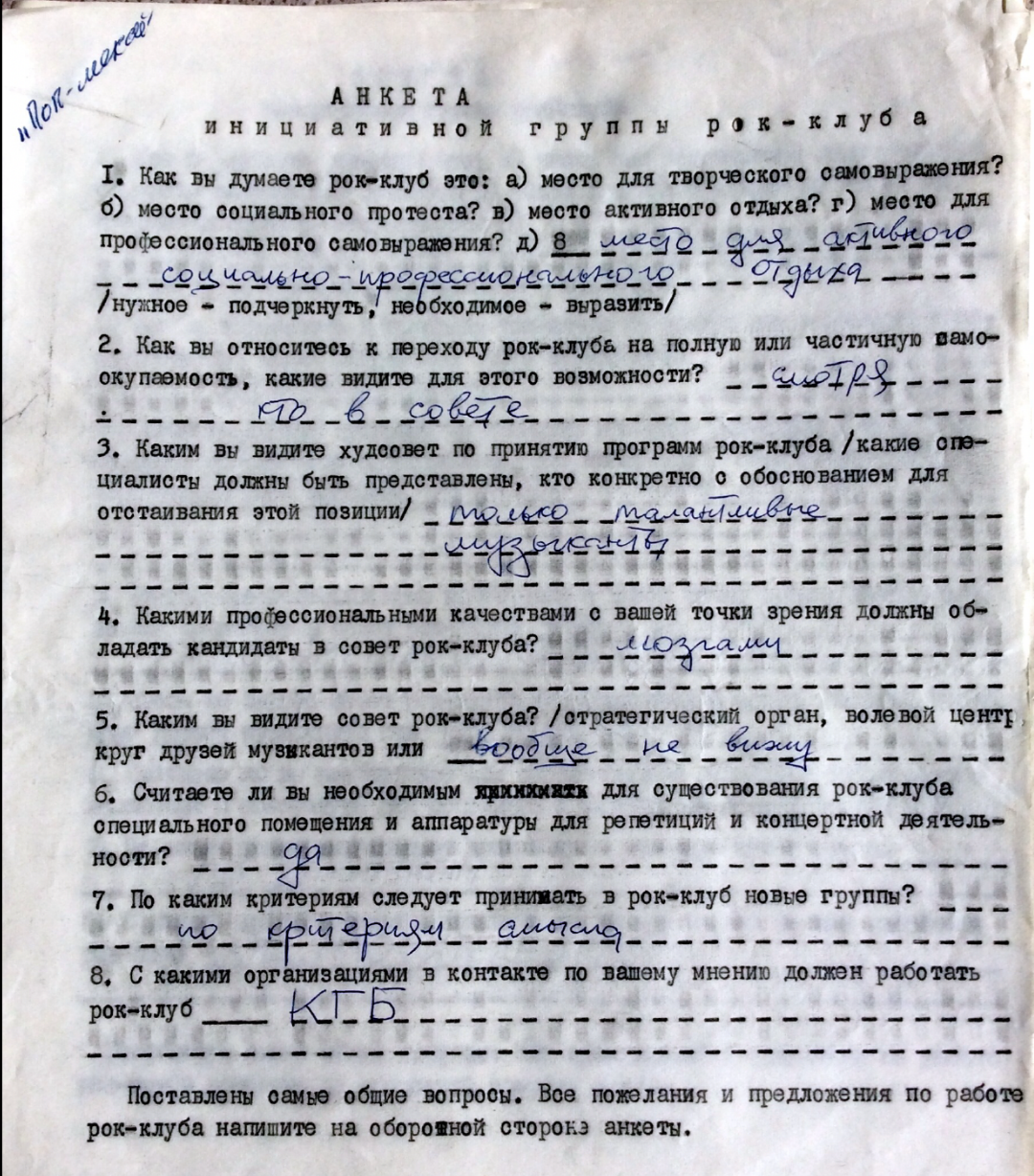

QUESTIONNAIRE of the rock club initiative group

- Question [underline or write in as needed]: In your opinion, is the rock club: a) a place for creative self-expression? b) a place of social protest? c) a place for active recreation? d) a place for professional self-expression? Answer: a place for active socio-professional recreation

- Question: What is your attitude toward the rock club's transition to full or partial self-sufficiency, what possibilities do you see for this? Answer: Depends on who is on the council

- Question: How do you envision the artistic council for approving rock club programs? Which specialists should be represented, who specifically with justification to defend this position? Answer: only talented musicians

- Question: In your opinion, what professional qualities should candidates for the rock club council possess? Answer: brains

- Question: How do you envision the rock club council? / As a strategic body, strong leadership center, circle of musician friends or... Answer: I don’t envision it at all

- Question: Do you consider it necessary for the rock club's existence to have special premises and equipment for rehearsals and concert activities? Answer: yes

- Question: By what criteria should new groups be admitted to the rock club? Answer: by the criterion of meaning

- Question: In your opinion, with which organizations should the rock club maintain contact? Answer: KGB

The most general questions have been posed. Please write all wishes and suggestions regarding the work of the rock club on the reverse side of the questionnaire.

Established in 1981, toward the end of the Brezhnev era, the Leningrad Rock Club (LRC) was a semi-official municipal organization dedicated to supporting amateur rock musicians. It was run and organized under the patronage and surveillance of the youth branch of the Soviet Communist Party, the Komsomol, and the KGB. By the late 1980s, the LRC fulfilled several related functions. First and foremost, it was the main institution dedicated to cultivating and protecting Soviet rock music. At the same time, however, it acted as the scene’s censor and setter of benchmarks. Membership in the club required a lengthy bureaucratic process that involved auditions, the vetting of song lyrics, a voting process by the club council (soviet), and, often enough, attending an appointment at the offices of the KGB. Despite these roadblocks, local groups were so desperate for musical equipment and performance venues that they paid due fealty to the rock club.

By the late 1980s, analogous organizations were springing up in most major cities across the USSR. The two primary incentives for Soviet municipalities to establish rock clubs were the relative ease of surveillance in case of ideological radicalism, and, perhaps more importantly, the ability to centrally profit from concert ticket sales. These organizations were subject to stringent control by the authorities, who regularly raided the premises and called off performances, in the process arresting and/or questioning both the musicians and their fans. The LRC and similar institutions exemplified the late-socialist ambivalence towards rock music, a previously “undesirable” cultural phenomenon now tolerated on the condition of submitting to state control.

Here, we see an official “Initiative Group Survey” from the 1980s-era LRC, completed by experimental musician and professional trickster Sergei Kuryokhin (1954-1996) of the band Pop Mekhanika. This brief questionnaire demonstrates the ideological ambivalence of the “organizational” and “bureaucratic” dimension of the late-Soviet rock music underground. On its face, the notion of presumably avant-garde rock performers completing a politically inflected survey as though the LRC were their “workplace” seems ridiculous. Yet even as it displays the ritualistic and performative aspects of late-socialist life, where cultural and artistic activities were heavily regimented, the document simultaneously reflects the performers’ self-aware irony. When Kuryokhin, for example, notes that the “KGB” is the most desirable organization with which LRC must maintain contact, he is deploying the late-Soviet aesthetic of stiob. Acknowledging the club’s dependence on the secret police calls attention to the situation’s absurdity and satirizes late-Soviet bureaucratic practices themselves.