Filed Under: Print > Entertainment > Grigory Malyshev, cover for the magazine "Krasnaia Burda" (Red Hogwash), Issue 1, October 1990

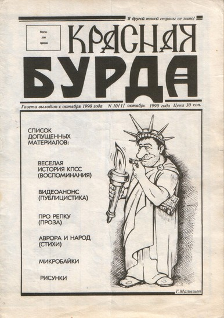

Grigory Malyshev, cover for the magazine "Krasnaia Burda" (Red Hogwash), Issue 1, October 1990

The long-running humor magazine Red Hogwash (Krasnaia Burda) first appeared in 1990. It was founded by former members of the KVN team Ural’skie Dvorniki (“The Ural Janitors”) comedians Alexander Sokolov, Yuri Isakov, and Vladimir Maurin. The publication’s title combined the archaic term for murky water, burda, with a reference to the far more popular and recognizable German fashion magazine Burda, in print in Russia since 1987. With the addition of the ironically nativizing “redness,” the founders evoked both the ancient Russian term for “beauty” and the Soviet flag. The magazine thus actively engaged the changing culture of the 1990s through a hodge-podge of student humor, subversive digs at perestroika and post-Soviet reality, caricature, and comic poetry. Initially a newspaper, Red Hogwash became a full-color magazine after 1994, developing a consolidated body of internal writers while also publishing comic writers and caricaturists from across the former Soviet Union.

The emergence of Red Hogwash as a new institution was part and parcel of the broader wave of student-driven comedy initiated by the re-establishment of KVN (Klub veselykh i nakhodchivykh or Club for the Joyful and the Witty), the popular televised variety and sketch comedy show. Initially screened on Channel 1 from 1961 to 1971, it was sidelined and eventually shut down during the Brezhnev era due to constant state censorship and KGB scrutiny. The show was restored to national television in 1986. Its return prompted the formation of numerous student groups and contests focused on writing and performing comedy.

The cover of the magazine’s first issue depicts a slovenly man dressed as the American Statue of Liberty lighting up a rolled cigarette with her torch. This irreverent image represents ambivalence and irony about perestroika, the rapidly approaching end of the Soviet Union, and presumed onset of “American-style democracy.” Red Hogwash continued to be published in print until 2018, moving entirely online after that year. It still maintains its brand of irreverent and ironic humor, including open mockery of Putin’s regime.