Filed Under: Video > Journalism > Evgeny Kiselev discusses the 21 September – 4 October 1993 Russian Constitutional Crisis on "Itogi"

Evgeny Kiselev discusses the 21 September – 4 October 1993 Russian Constitutional Crisis on "Itogi"

On 21 September 1993, Yeltsin issued a decree that disbanded both chambers of the bicameral legislature of the Russian Federation and called for a new Constitution. This unconstitutional act was the result of longstanding conflicts between President and Parliament that had been brewing since 1992, when Yeltsin had begun privatizing the post-Soviet economy. Though Yeltsin attempted to justify his decision through a lengthy television address, he failed to convince either the majority of Russians or the lawmakers themselves. The legislature mounted an armed resistance to Yeltsin, attempting to impeach him even as he scheduled new presidential elections for March 1994. Enraged by the depredations of the neoliberal economic reforms that had impoverished and immiserated so many of them, tens of thousands of Muscovites took to the streets to express their support for Parliament over Yeltsin. The standoff — which included bloody clashes between police and anti-Yeltsin demonstrators — continued until October 3, when pro-parliament paramilitaries stormed the Ostankino Technical Center. About 50 people were killed in the resulting clash, whereupon Yeltsin declared a state of emergency and ordered the bombing and storming of the White House. This action brought an end to the crisis, but at a steep cost: unlike in the 1991 putsch, where there were only 3 casualties, in 1993 about 120 people died, and about 400 were wounded.

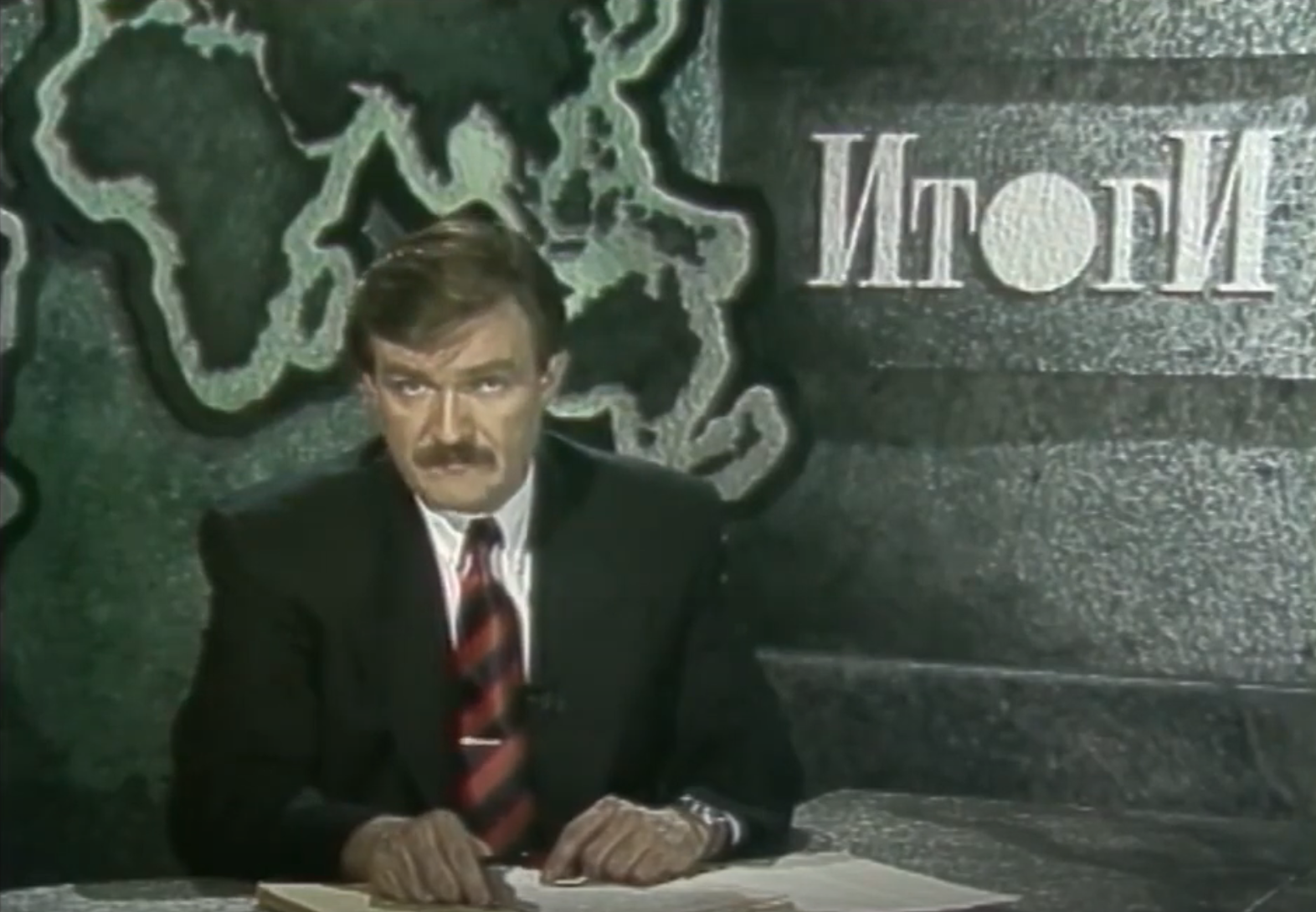

These are the events journalist Evgeny Kiselev discusses in his inaugural broadcast on NTV — the network owned and operated by prominent oligarch Vladimir Gusinsky — on the weekly news analysis program Itogi. Following a brief intro sequence whose spare, dark color palette alludes to the show’s seriousness of purpose, Kiselev appears onscreen to re-introduce himself to audiences after a three-week hiatus. “We are now living in a completely different country,” he opines, before drawing an explicit comparison between the 1993 constitutional crisis and the 1991 putsch. Paraphrasing Karl Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1851-2), Kiselev continues, “they say that history repeats itself: once as tragedy, then as farce.” Yet “in contemporary Russian history, it seems that [this dictum] is reversed: the events that occurred at the White House in 1991 look like a farce to us today, against the background of the real tragedy that unfolded on 3 and 4 October. For two days, Moscow was basically at war with itself.” Following this introduction, the screen begins displaying footage of the events that took place between 21 September and 3 October, with Kiselev supplying detail in voiceover.

At approximately 6 minutes 30 seconds, the sequence concludes and Kiselev returns to the screen. What follows is a clear statement of allegiance to the new values of integrity, openness, and respect that many hoped would define the Russian media landscape after perestroika. “So much has been said and written about the denouement that followed that, today, we decided not to say anything,” Kiselev states. “We decided, instead, to show—without comment—some chronologically arranged documentary footage of the events that unfolded on the streets of Moscow on 3 and 4 October. We attempt to show you this tragedy just as it was, in all its terrible unsightliness, embellishing nothing and concealing nothing. Take a look and decide for yourself what really happened.”