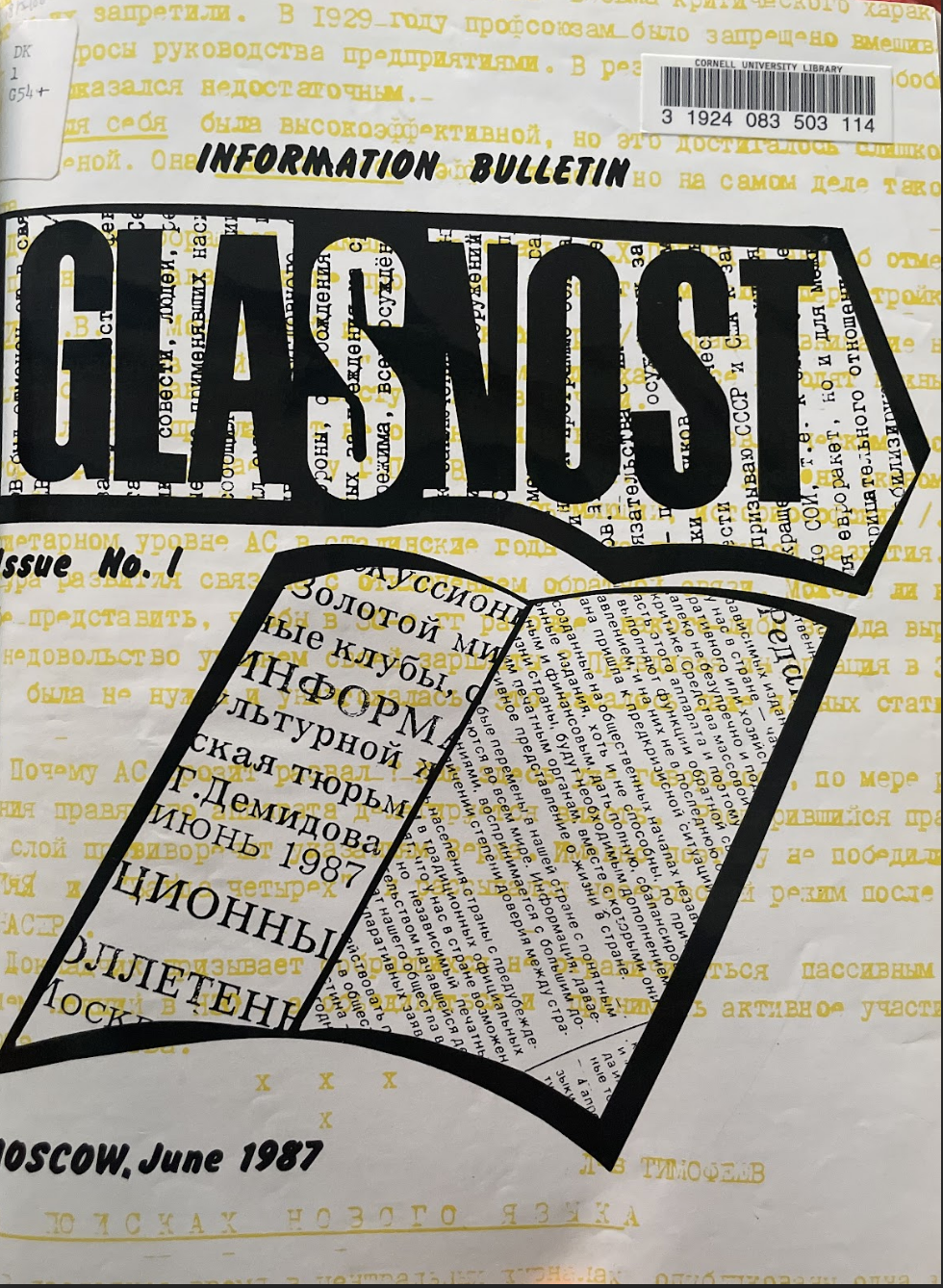

Filed Under: Print > Journalism > "Glasnost. Information Bulletin"

"Glasnost. Information Bulletin"

[2 items]

Declaration of the Editors

On the Information Bulletin Glasnost and the Anthology Glasnost

Currently the need for reform in all spheres of life of society-political, economic, social, and cultural—has become evident. Not so long ago, few people spoke openly about the need for change. Today everyone speaks about change, and the nation's leaders more insistently than others. It is precisely they who define the events of the preceding period as "pre-crisis phenomena." It is precisely the leaders of the nation who have declared that there must be a policy of radical change and stated that there is no other way out.

It would seem that those people who had already spoken and written the truth about life in their society, despite prohibitions and repressions, would find it easier to become a part of this process. It would seem that all they had to do was continue their cause, and that would be that, but it is not so simple, because they must consider not only their actions but also the counteractions. It is no secret that the policy of change encounters active resistance from those in the political and economic apparatus who have brought the nation, directly or indirectly, to this “pre-crisis situation.” Until now these individuals have continued to occupy several key positions, and they actively stand in the way of restructuring. Their major argument is the fear of losing control over the nation. These forces should not be underestimated.

We realize that one can impede the fledgling restructuring process not only by actively resisting the reforms, but also provoking the actions of the reformers’ opponents. It is not easy in today's complicated political situation either to support with confidence or to reject outright any evaluation. We are aware of the danger of taking action, but inaction is also unacceptable. It is our feeling and conviction that the fate of the nation and the fate of humanity are being decided now, and this forces us to seek our way of participating in the current process of change.

The first steps are clear. We begin by publishing the Information Bulletin Glasnost and a larger publication, the anthology Glasnost, which will contain articles and materials on important contemporary problems. Both publications are independent organs with the purpose of facilitating democratic consciousness in society. The premier [sic] issue of the Glasnost anthology, which was prepared at the same time as the premier [sic] issue of the Bulletin, is devoted to the most important, in our view, political event of 1987—the release of political prisoner in the USSR.

Both journals are intended as completely legitimate publications, registered with the appropriate state organizations. The Bulletin and the Anthology will highlight to the same degree problems of the human-rights movement in the country and other socially significant issues, such as ecology, culture, economics and social life, while bringing together on their pages a broad circle of highly qualified specialists.

The need for independent publications is dictated by the fact that the entire print medium in our country is part of that very political, administrative, or economic apparatus which is far from irreproachable and has recently been subjected to open criticism. Since the mass media are part of this apparatus, they do not adequately provide the feedback necessary between society and the feedback necessary between society and the leadership, and the media share the blame for the fact that the nation has come to a pre-crisis situation.

Independent informational publications, while not capable of presenting a totally comprehensive and balanced picture of the life in the country for organizational and financial reasons, will nonetheless be a necessary complement to existing press organs, and together with them they will present a sufficiently objective idea about life in our society.

One more important aspect is the fact that all changes in our country are perceived with great interest by the entire world, and information provided by independent publications will be received with greater trust than the official ones and will increase the degree of trust between nations.

Finally, a large part of the country's population is biased against traditional official publications. Now these people will see that a publication which passes inspection by Glavlit but is still independent is possible in our country. This will be serious evidence of the democratization which is beginning to take place and will enliven the spiritual climate of our society far more than tens and hundreds of declarations.

Today we have only one means of encouraging change m the nation—to embody these changes in the printed word and in the social consciousness, and to present them objectively. Truth belongs to society, and what was a secret yesterday is being discussed today openly and everywhere. It is impossible to remain silent.

—The Editors

The first issue of Glasnost: Information Bulletin appeared in June 1987, making it one of the earliest self-published journals during perestroika and part of the rapidly expanding late-Soviet independent press. Up until the early years of perestroika, the Soviet government approached self-published (samizdat) literature unforgivingly, often jailing those who wrote it and sometimes those who circulated it. During perestroika, however, the government tacitly permitted samizdat, paving the way for a flourishing independent press that enabled greater citizen participation in society and politics.

The editor in chief of Glasnost: Information Bulletin was Sergei Grigoriants (1941-2023), a Moscow State University-trained journalist of Armenian and Ukrainian descent. In 1975, as the samizdat publication Chronicle of Current Events reported, he was sentenced to five years in prison for circulating the unauthorized magazines Grani and Mosty as well as a catalogue of Russian works published abroad in 1971. Upon his release in 1982, Grigoriants immediately resumed self-publishing, contributing information about human rights violations in the USSR to a publication titled Bulletin V. In 1984, he was again arrested and sentenced to ten years hard labor. He was freed in 1987 under an amnesty for political prisoners under Gorbachev. That same year, he published the first issue of Glasnost.

Several factors made Glasnost: Information Bulletin an unusual and influential instantiation of the late-Soviet independent press. First, the Bulletin appeared almost regularly for three years—far longer than most self-published newspapers of the time. Second, Grigoriants was already known abroad in 1987, which likely contributed to the translation and publication of Glasnost abroad in Western Europe and the United States by the Center for Democracy in New York. Finally, in 1989, Girgoriants received the Golden Pen of Freedom Award from the World Association of Newspapers—a prize that, in addition to prestige, aimed to provide some protection to writers from hostile governments.

Glasnost: Information Bulletin struck a critical tone against the Soviet government, but, like much late-Soviet dissident activity, sought to take the Soviet government at its word—in this case, the policies of perestroika and especially glasnost.