Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Nina Andreeva’s “I Cannot Forsake My Principles”

Nina Andreeva’s “I Cannot Forsake My Principles”

"I Cannot Forsake My Principles," by Nina Andreeva

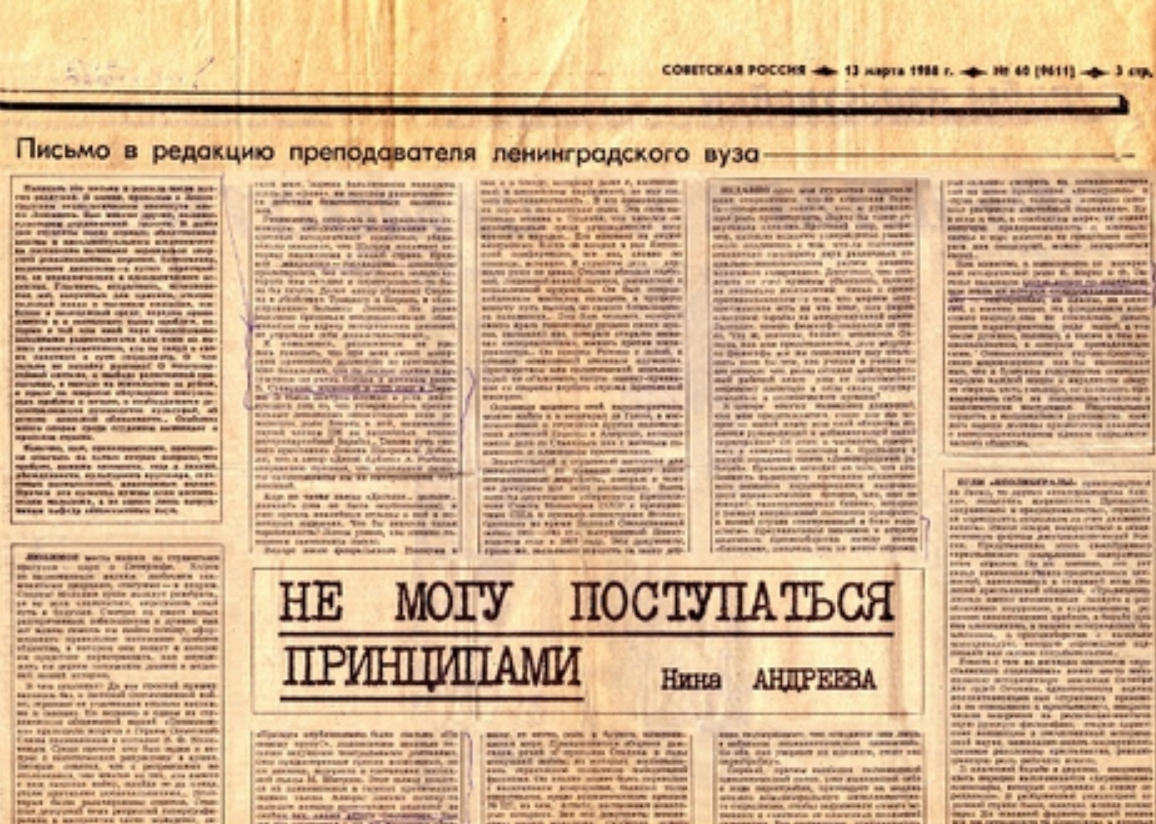

Sovetskaia Rossiia, March 13, 1988

Sovetskaia Rossiia, March 13, 1988

I decided to write this letter after lengthy deliberation. I am a chemist, and I lecture at Leningrad's Lensovet Technology Institute. Like many others, I also look after a student group. Students nowadays, following the period of social apathy and intellectual dependence, are gradually becoming charged with the energy of revolutionary changes. Naturally, discussions develop about the ways of restructuring and its economic and ideological aspects. Glasnost, openness, the disappearance of zones where criticism is taboo, and the emotion heat of mass consciousness (especially among young people) often result in the raising of problems that are , to a greater or lesser extent, "prompted" either by Western radio voices or by those of our compatriots who are shaky in their conceptions of the essence of socialism. And what a variety of topics that are being discussed! A multiparty system, freedom of religious propaganda, emigration to live abroad, the right to broad discussion of sexual problems in the press, the need to decentralize the leadership of culture, abolition of compulsory military service. There are particularly numerous arguments among students about the country's past.

Of course, we lecturers must answer the most controversial questions, and this demands, in addition to honesty, knowledge, conviction, broad cultural horizons, serious reflection, and considered opinions. Moreover, these qualities are needed by all educators of young people and not only by members of social science department staffs.

Petergof Park is a favorite spot for the walks I take with my students. We stroll along the snow-covered paths, enjoy looking at the famous palaces and statues, and we argue. We do argue! The young souls are eager to investigate all complexities and to map out their path in to the future. I look at my ardent young interlocutors, and I think to myself how important it is to help them to discover the truth and shape a correct perception of the problems of the society in which they live and which they will have to restructure, and how to give them a correct perception of our history, both distant and recent.

What are the misgivings? Here is a simple example: You would think that plenty has been written and said about the Great Patriotic War against the Nazi invasion and the heroism of those who fought in it. Recently, however, a student hostel in our Technology Institute organized a meeting with Hero of the Soviet Union and Colonel of the Reserve V. Molozeyev. Among other things, he was asked a question about political repressions in the army. The veteran replied that he had never come across any repressions and that many of those who fought in the war with him form its beginning to its end became high-ranking miliary leaders. Some were disappointed by this reply. Now that it has become topical, the subject of repressions has been blown out of all proportion in some young people's imaginations and overshadows any objective interpretation of the past. Examples like this are by no means isolated.

It is, of course, extremely gratifying that even "technicians" are keenly interested in theoretical problems of the social sciences. But I can neither accept nor agree with all too much of what has now appeared. Verbiage about "terrorism," "the people's political servility," "uninspired social vegetation," "our spiritual slavery," "universal fear," "dominance by boors in power" - these are often the only yarns used to weave the history of our country during the period of transition to socialism. It is, therefore, not surprising that nihilistic sentiments are intensifying among some students and that there are instances of ideological confusion, loss of political bearings, and even ideological omnivorousness. At times you even hear claims that the time has come to take Communist to task for having allegedly "dehumanized" the country's life since 1917.

The Central Committee February plenum emphasized again the insistent need to ensure that "young people are taught a class-based vision of the world and an understanding of the links between universal and class interests, including an understanding of the class essence of the changes occurring in our country." Such a vision of history and of the present is incompatible with the political anecdotes, base gossip, and controversial fantasies that one often encounters today.

I have been reading and rereading sensational articles. For example, what can you people gain (apart from disorientation) from revelations about "the counterrevolution in the USSR in the late 1920s and early 1930s" or about Stalin's "guilt" for the rise to power of fascism and Hitler in Germany? Or the public "reckoning" of the number of "Stalinists" in various generations and social groups?

We are Leningraders, and therefore we were particularly interested in watching recently the good documentary movie about Sergei Kirov [a popular Bolshevik leader in Leningrad, killed in 1934; the killing was allegedly organized by Stalin, who considered Kirov a dangerous rival and who used it as a pretext to launch repressions]. But at times the text that accompanied the film not only diverged from the movie's documentary evidence but even made it appear somewhat ambiguous. For example, the movie would show the outburst of keenness, joie de vivre, and spiritual enthusiasm of people building socialism, while the announcer's text would be about repression, about lack of information.

I am probably not the only one to have noticed that the calls by party leaders asking the "exposers" to pay attention also to the factual and real achievements at different stages of socialist construction seem, as if by command, to bring forth more and more outbursts of "exposures." Mikhail Shatrov's plays are a notable phenomenon in this - alas! - infertile field. On the day the 26th Party Congress opened, I went to see the play "Blue Horses on Red Grass." I recall the young people's excitement at the scene in which Lenin's secretary tries to empty a teapot over his head, confusing him with an unfinished clay sculpture. Asa matter of fact, some young people had arrived with prepared banners whose essence was to sling mud at our past and present. In "The Brest Peace" the playwright and director make Lenin kneel before Leon Trotsky. So much for the symbolic embodiment of the author's concept. This is further developed in the play "Onward! Onward! Onward!" A play is, of course, not a historical document. But even in a work of art, truth is guaranteed by nothing but the author's stance. Especially in the case of political theater.

Playwright Shatrov's stance has been analyzed in detail in a well-reasoned way in reviews by historians published in Pravda and Sovetskaya Rossiya. I would like to express my own opinion. In particular, it is impossible not to agree that Shatrov deviates substantially from the accepted principles of socialist realism. In covering a most crucial period in our country's history, he absolutizes the subjective factor in social development and clearly ignores the objective laws of history as displayed in the activity of the classes and the masses. The role played by the proletarian masses and the Bolshevik party is reduced to the "background" against which the actions of irresponsible politicians unfold.

The reviewers, on the basis of the Marxist-Leninist methodology of analyzing specific historical processes, have convincingly shown that Shatrov distorts the history of socialism in our country. He objects to the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat, without whose historical contribution we would have nothing to restructure today. The author goes on to accuse Stalin of the assassinations of Trotsky and Kirov and of "isolating" Lenin while he was ill. But how can anyone possibly make biased accusations against historical figures without bothering to adduce any proof?

Unfortunately, the reviewers have failed to show that, despite all his pretensions as an author, the playwright is far from original. I got the impression that, in the logic of his assessments and arguments, he rather closely follows the line of Boris Suvarine's book published in Paris in 1935. In his play, Shatrov makes his characters say things that were said by the adversaries of Leninism about the course of the revolution, about Lenin's role in it, about the relationships between Central Committee members at different stages of inner party struggle. This is the essence of Shatrov's "fresh reading" of Lenin. Let me add that Anatoly Rybakov, author of Children of the Arbat, has frankly admitted that he borrowed some incidents from migr publications.

Without having read the play "Onward! Onward! Onward!" (it had not been published yet), I read rapturous reviews of it in some publications. What could have been the meaning of such haste? I learned later that the play was being hastily staged.

Soon after the February plenum, Pravda published a letter entitled "Coming Full Circle?" signed by eight of our leading theatrical figures. They warned against what they saw as possible delays in staging Shatrov's play. This conclusion was drawn on the basis of some critical reviews of the play in the press. For some unknown reason, the authors of the letter excluded the writers of the critical reviews from the category of those "who treasure the fatherland." How can this be reconciled with their desire for a "stormy and impassioned" discussion of our history, both distant and recent? It appears that they alone are entitled to their opinion.

In the numerous discussions now taking place on literally all questions of the social sciences, as a college lecturer I am primarily interested in the questions that have a direct effect on young people's ideological and political education, their moral health, and their social optimism. Conversing with students and deliberating with them on controversial problems, I cannot help concluding that our country has accumulated quite a few anomalies and one-sided interpretations that clearly need to be corrected. I would like to dwell on some of them in particular.

Take, for example, the question of Joseph Stalin's place in our country's history. The whole obsession with critical attacks is linked with his name, and in my opinion this obsession centers not so much on the historical individual himself as on the entire highly complex epoch of transition, an epoch linked with unprecedented feats by a whole generation of Soviet people who are today gradually withdrawing from active participation in political and social work. The industrialization, collectivization, and cultural revolution which brought our country to the ranks of the great world powers are being forcibly squeezed into the "personality cult" formula. All of this is being questioned. Matters have gone so far that persistent demands for "repentance" are being made of "Stalinists" (and this category can be taken to include anyone you like). There is rapturous praise for novels and movies that lynch the epoch of "storms and onslaught," which is presented as a "tragedy of the peoples." It is true that such attempts to place historical nihilism on a pedestal do not always work. For example, a movie showered with praise by critics can be extremely cooly received by the majority of viewers despite the unprecedented publicity hype [Andreeva is referring here to Tengiz Abuladze's anti-Stalinist film Repentance].

Let me say right away that neither I nor any members of my family were in any way involved with Stalin, his retinue, his associates, or his extollers. My father was a worker at Leningrad's port, my mother was a fitter at the Kirov plant. My elder brother also worked there. My brother, my father, and my sister died in battles aginst Hitler's forces. One of my relatives was repressed and then rehabilitated after the 20th Party Congress. I share all of the Soviet people's anger and indignation about the mass repressions that occurred in the 1930s and 1940s and with the party-state leadership of the time, which is to blame. But commonsense resolutely protests aginst the monochrome depiction of contradictory events that now domaintes in some press organs.

I support the party's call to uphold the honor and dignity of the trailblazers of socialism. I think that these are the party-class positions from which we must assess the historical role of all leaders of the party and the country, including Stalin. In this case, matters cannot be reduced to their "court" aspect or to abstract moralizing by persons far removed both from those stormy times and from the people who had to live and work in those times, and to work in such a fashion as to still be an inspiring example for us today.

For me, as for many people, a decisive role in my assessment of Stalin is played by the candid testimony of contemporaries who clashed directly with him on our side of the barricades as well as on the other side. It is the latter who are quite interesting. For instance, take British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who, back in 1919, was proud of his personal contribution to organizing the military intervention by fourteen foreign states against the young Soviet republic and who, exactly forty years later, used the following words to describe Stalin, one of his most formidable political opponents:

"He was an oustanding personality who left his mark on our cruel time during his lifetime. Stlain was a man of exceptional energy, erudition, and unbending willpower, harsh, tough, and ruthless in both action and conversation, and even I, brought up in the English Parliament, could not oppose him in any way....A gignatic force resounded in his words. This force was so great in Stalin that he seemed unique among the leaders of all times and all peoples. His effect on people was irresistible. Whenever he entered the Yalta conference hall, we all rose as if by command. And strangely, we all stood to attention. Stalin possessed a profound, totally unflappable, logical, and sensible wisdom. He was a past master at finding a way out of the most hopeless situation at a difficult time....He was a man who used his enemeies to destory his enemy, forcing us - whome he openly called imperialists - to fight the imperialists....He took over a Russia still using the wooden plow, and left it equipped with atomic weapons."

This assessment and admission by the loyal custodian of the British Empire cannot be attributed to either pretense or political timeserving. Long and frank conversations with young interlocutors lead us to the conlcusion that the attacks on the state of the dictatorship of the proletariat and our country's leaders at this time have not only political, ideological, and moral causes, but also a social substratum. There are quite a few people interested in expanding the bridgehead for these attacks, and they are to be found not just on the other side of our borders. Along with professional anti-Communists in the West who picked the supposedly democratic slogan "anti-Stalinism" a long time ago, the offspring of the classes overthrown by the October Revolution (by no means all of whom have managed to forget the material and social losses incurred by their forebears) are still alive and prospering. One must add to them the spiritual heirs of Dan and Martov and other adherents of Russian social democracy, the spiritual followers of Trotsky or Yagoda, and the offspring of NEP-men, basmachy, and kulaks with grudges against socialism. [Fyodor Dan and Yulii Martov were leaders of the Menshevik wing of Russian Social Democracy who opposed Lenin's policies. Genrikh Yagoda was Stalin's head of security forces during the 1930s. NEP-men were entrepreneurs who flourished under the New Economic Policy (NEP). Basmachy were members o the local resistnace to Soviet control of Central Asia during the 1930s]

I think that, no matter how controversial and complex a figure in Soviet history Stalin may be, his genuine role in the building and defense of socialism will sooner or later be given an objective and unambiguous assessment. Of course, unambiguous does not mean an assessment that is one-sided, that whitewashes, or that eclectically sums up contradictory phenomena making it possible subjectively (albeit with slight reservations) "to forgive or not forgive," "to reject or retain." Unambiguous means primarily a specific historical assessment detached from short-term consdierations which would demonstrate - according to historical results! - the dialectics of the correlation between the individual's actions and the basic laws governing society's development. In our country these laws were also linked with the answer to the question "Who will defeat whom?" in its domestic as well as international aspects. If we are to adhere to the Marxist-Leninsit methodology of historical analysis then, in Mikhail Gorbachev's words, we must primarily and vividly show how the millions of people lived, how they worked, and what they believed in, as well as the coupling of victories and failures, discoveries and errors, the bright and the tragic, the revolutionary enthusiasm of the masses and the violation of soicalist legality and even crimes at times.

I was puzzled recently by the revelation of one of my students that the class struggle is supposedly an obsolete term, just like the leading role of the proletariat. It would be alright if she were the only one to claim this. A furious argument was generated, for example, by a respected academician's recent assertion that present-day relations between states from the two different socioeconomic systems apparently lack any class content. I assume that the academician did not deem it necessary to explain why it was that, for several decades, he wrote exactly the opposite, namely, that peaceful coexistence is nothing but a form of class struggle in the international arena. It seems that the philosopher has now rejected this view. Never mind, people can change their minds. It does seem to me, however, that duty would nevertheless command a leading philosopher to explain - at least to those who have studied and are studying his books - what is happening today; does the mternational working class no longer oppose world capital as embodied in its state and political organs?

It seems to me that many of the present debates center on the same question: Which class or stratum of society is the leading and mobilizing force of perestroika? This in particular was discussed in an interview with writer Alexander Prokhanov published by our city newspaper Leningradskii rabochii. [Prokhanov is a conservative writer who actively defends the military establishment] Prokhanov proceeds from the premise that the specific nature of the present state of social consciousness is typified by the presence of two ideological currents or, as he puts it, "alternative towers" which are trying, from different directions, to overcome the "socialism that has been built in battles'' in our country. Although he exaggerates the significance and acuteness of the duel between these two "towers," the writer is nevertheless correct in emphasizing that "they agree only on the slaughter of socialist values." But both of them, so their ideologists claim, are "for perestroika."

It is the champions of "left-wing liberal socialism" [according to Andreeva, these are writers, artists and historians strongly critical of Stalin's crimes] who shape the tendency toward falsifying the history of socialism. They try to make us believe that the country's past was nothing but mistakes and crimes, keeping silent about the greatest achievements of the past and the present. Claiming full possession of historical truth, they replace the sociopolitical criterion of society's development with scholastic ethical categories. I would very much like to know who needed to ensure, and why, that every prominent leader of the party Central Committee and the Soviet government - once they were out of office - was compromised and discredited because of actual and alleged mistakes and errors committed when solving the most complex of problems in the course of historical trailblazing? Where are the origins of this passion of ours to undermine the prestige and dignity of the leaders of the world's first socialist country?

Another peculiarity of the views held by the "1eft-wing liberals" is an overt or covert cosmopolitan tendency, some kind of non-national "internationalism." I read somewhere about an incident after the revolution when a delegation of merchants and factory owners called on Trotsky "as a Jew" at the Petrograd soviet to complain about the oppression by the Red Guards, and he declared that he was "not a Jew but an internationalist," which really puzzled the petitioners. In Trotsky's view, the idea of "nation" connoted a certain inferiority and limitation compared with the "international." This is why he, emphasizing October's "national tradition," wrote about "the national element in Lenin," claimed that the Russian people "had inherited no cultural heritage at all," and so on. We are somehow embarrassed to say that it was indeed the Russian proletariat, whom the Trotskyites treated as "backward and uncultured," who accomplished - in Lenin's words - "three Russian revolutions" and that the Slavic peoples stood in the vanguard of mankind's battle against fascism.

This, of course, is not to denigrate the historical contribution of other nations and ethnic groups. This, as it is said nowadays, is only to ensure that the full historical truth is told. When students ask me why thousands of small villages in the nonblack-soil lands and Siberia are deserted, I reply that this is part of the high price we had to pay for victory and for the postwar restoration of the national economy, just like the irretrievable loss of large numbers of monuments of Russian national culture. I am also convinced that any denigration of the importance of consciousness produces a pacifist erosion of defense and patriotic consciousness as well as a desire to categorize the slightest expressions of Great Russian national pride as manifestations of the chauvinism of a great power. Here is something else that worries me: the practice of "refusenikism" of socialism is nowadays linked with militant cosmopolitanism. ["Cosmopolites and refuseniks" are code words for Jews, who are often perceived as overtly liberal troublemakers who do not possess Russian national pride. The term "cosmopolites" was coined during the Stalin period] Unfortunately, we remember this suddenly only when its adherents plague us with their outrages in front of the Smolny or at the Kremlin walls. Moreover, we are gradually being trained to perceive the aforementioned phenomenon as some sort of almost innocent change of "place of residence" rather than as class or national betrayal by persons who (most of them) graduated from colleges and completed their postgraduate studies thanks to our own country's funds. Generally speaking, some people are inclined to look upon "refusenikism" as some sort of manifestation of "democracy" and the "rights of man," whose talents were prevented from flourishing by "stagnant socialism." And if it so happens that people over there, in the "free world," fail to appreciate bubbling entrepreneurship and "genius" and the special services are not interested in the trading of conscience, one can always return.

While "neoliberals" look toward the West, the proponents of the other "alternative tower," to use Prokhanov's expression, the "protectionists and traditionalists," are striving "to overcome socialism by regression," in other words, by reverting to the social forms of presocialist Russia. The spokesmen for this variety of "peasant socialism" are fascinated by this image. ["traditionalists" and "peasant socialists" refer to Russian nationalists who identify with the Russian peasantry] In their opinion, the moral values accumulated by peasant communes in the misty fog of the centuries were lost a hundred years ago. The "traditionalists" certainly deserve credit for what they have done for the exposure of corruption, the fair solution of ecological problems, the struggle against alcoholism, the protection of historical monuments, and the opposition to dominance by mass-culture, which they correctly evaluate as consumerist media.

At the same time, the views of the ideologists of "peasant socialism" show a lack of understanding of October's historical importance for the fate of the fatherland, a one-sided assessment of collectivization as a "terrible atrocity against the peasantry," an uncritical perception of mystical religious Russian philosophy and the old czarist concepts in our historical science, and an unwillingness to perceive the postrevolutionary stratification of the peasantry and the revolutionary role of the working class. When it comes to the class struggle in the countryside, for example, excessive emphasis is often placed on the "rural" commissars who "shot middle income peasants in the back." There were, of course, all sorts of commissars at the height of the revolutionary conflagration in our vast country. But in the mainstream of our life are commissars who were shot at, commissars who had stars carved on their backs or who were burned alive. The price the "attacking class" had to pay consisted not only of the lives of commissars, chekists, rural Bolsheviks, members of the committees of poor peasantry, or the "Twenty Thousand" but also those of the first tractor drivers, rural correspondents, girl teachers, rural Komsomol members and the lives of tens of thousands of other unknown fighters for socialism. [Andreeva emphasizes the losses of the commissars (political workers of the party) and the chekists (members of the security forces)]

The education of young people is made even more complex by the fact that informal organizations and associations are being formed around the ideas of "neoliberals" and "neo-Slavophiles." Sometimes the upper hand in their leadership is gained by extremist elements capable of provocations. A politicization of these informal organizations on the basis of a by-no-means socialist pluralism has recently emerged. Leaders of these organizations often speak of "power sharing" on the basis of a "parliamentary system," "free trade unions," "autonomous publishing houses," and so on. In my view, all this leads to the conclusion that the main and cardinal issue of the debates now taking place in the country is this: whether or not to recognize the leading role of the party and the working class in socialist building and therefore in perestroika with all the ensuing theoretical and practical conclusions for politics, economics, and ideology.

It seems to me that the question of the role and position of socialist ideology is extremely acute today. The authors of timeserving articles [conservatives often accuse proreform writers of duplicity for condemning Brezhnev-era policies that they previously supported wholeheartedly] circulating under the guise of moral and spiritual "cleansing" erode the dividing lines and criteria of scientific ideology, manipulate glasnost, and foster nonsocialist pluralism, which applies the brakes on perestroika in the public conscience. This has a particularly painful effect on young people which, I repeat, is clearly sensed by us, the college lecturers, schoolteachers, and all who have to deal with young people's problems. As Mikhail Gorbachev said at the CPSU Central Committee February plenum, "our actions in the spiritual sphere - and maybe primarily and precisely there - must be guided by our Marxist-Leninist principles. Principles, comrades, must not be compromised on any pretext whatever."

This is what we stand for now, and this is what we will continue to stand for. Principles were not given to us as a gift, we have fought for them at crucial turning points in the fatherland's history.

Source: Isaac J. Tarasulo (ed.), Gorbachev and Glasnost. Viewpoints from the Soviet Press (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1989): 277-290.

On 13 March 1988, the daily newspaper Sovetskaia Rossiia published a lengthy open letter by Leningrad chemistry lecturer Nina Andreeva (1938-2020). The text received an unusual amount of space, covering the entirety of the paper’s third page. Typically, published letters were excerpted, amounting to a few lines or, at the limit, up to a quarter of a single column on a page. Further signaling the importance they attributed to her opinion, editors included an annotation of the letter, along with a photo of Andreeva surrounded by her students, on the front page.

Titled “I Cannot Forsake my Principles [Ne mogu postupat’sia printsypami],” Adnreeva’s letter argued for the preservation of Stalin’s image, legacy, and values in Soviet society, a deeply conservative opinion that resonated primarily with the old guard in the Communist Party. Other readers, both inside and outside the USSR, were scandalized, questioning whether it was possible to reform Soviet socialism at all. The publication of “I Cannot Forsake My Principles” cast the inner workings of Soviet print media into sharp relief. True, the letter was authentically written by Andreeva, who stood by her words until her death in 2020, but it was clear that it had not appeared in a premier Soviet news outlet by accident. Andreeva’s text could only have been published with permission from powerful Soviet authorities, including Chairman of the Central Committee Yegor Ligachev (1920-2021) and Sovetskaia Rossiia’s editor-in-chief, Valentin Chikin (1932-). These connections underscore the proximity of politics to print media during perestroika, popularly known as a period of “hands-off” treatment by the government—even before the ratification of the Press Law of 1990 legally severed those connections.

Andreeva’s letter also spotlighted the feedback loops among media channels, showing how an article could go “viral” in the 1980s. In part because of the enormous amount of space Sovetskaia Rossiia had devoted to the letter, other outlets across the USSR took up discussion of Andreeva’s views and emphasized the broad support these supposedly enjoyed. Television programs featured special episodes dedicated to the letter, and 932 newspapers across the USSR syndicated its publication within a few weeks. It is difficult to determine whether editors and producers spent time on Andreeva because they felt pressure to do so, or because her letter presented a convenient opportunity for conservative critics of Gorbachev’s reform to speak their minds.

Despite the limits on Soviet free speech even during glasnost, the publication of Andreeva’s letter and the intense discussion it engendered demonstrated how much Soviet readers continued to see the press as a venue for publicizing their views and holding public discussion. Soon after Andreeva’s text appeared, readers began penning responses, both critical and supportive, and sending them to newspapers on the local, regional, and national levels; to various Party organs, including the Central Committee and even Gorbachev himself; and to Andreeva, at home and at work. This massive response, with letters numbering in the tens of thousands, showed that—quite against the grain of the sentiments Andreeva expressed—a freer public sphere was beginning to form in the Soviet Union of the late 1980s.

Titled “I Cannot Forsake my Principles [Ne mogu postupat’sia printsypami],” Adnreeva’s letter argued for the preservation of Stalin’s image, legacy, and values in Soviet society, a deeply conservative opinion that resonated primarily with the old guard in the Communist Party. Other readers, both inside and outside the USSR, were scandalized, questioning whether it was possible to reform Soviet socialism at all. The publication of “I Cannot Forsake My Principles” cast the inner workings of Soviet print media into sharp relief. True, the letter was authentically written by Andreeva, who stood by her words until her death in 2020, but it was clear that it had not appeared in a premier Soviet news outlet by accident. Andreeva’s text could only have been published with permission from powerful Soviet authorities, including Chairman of the Central Committee Yegor Ligachev (1920-2021) and Sovetskaia Rossiia’s editor-in-chief, Valentin Chikin (1932-). These connections underscore the proximity of politics to print media during perestroika, popularly known as a period of “hands-off” treatment by the government—even before the ratification of the Press Law of 1990 legally severed those connections.

Andreeva’s letter also spotlighted the feedback loops among media channels, showing how an article could go “viral” in the 1980s. In part because of the enormous amount of space Sovetskaia Rossiia had devoted to the letter, other outlets across the USSR took up discussion of Andreeva’s views and emphasized the broad support these supposedly enjoyed. Television programs featured special episodes dedicated to the letter, and 932 newspapers across the USSR syndicated its publication within a few weeks. It is difficult to determine whether editors and producers spent time on Andreeva because they felt pressure to do so, or because her letter presented a convenient opportunity for conservative critics of Gorbachev’s reform to speak their minds.

Despite the limits on Soviet free speech even during glasnost, the publication of Andreeva’s letter and the intense discussion it engendered demonstrated how much Soviet readers continued to see the press as a venue for publicizing their views and holding public discussion. Soon after Andreeva’s text appeared, readers began penning responses, both critical and supportive, and sending them to newspapers on the local, regional, and national levels; to various Party organs, including the Central Committee and even Gorbachev himself; and to Andreeva, at home and at work. This massive response, with letters numbering in the tens of thousands, showed that—quite against the grain of the sentiments Andreeva expressed—a freer public sphere was beginning to form in the Soviet Union of the late 1980s.