Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Citizen K.'s "Kitchen Diary" in "Komsomolskaya Pravda"

Citizen K.'s "Kitchen Diary" in "Komsomolskaya Pravda"

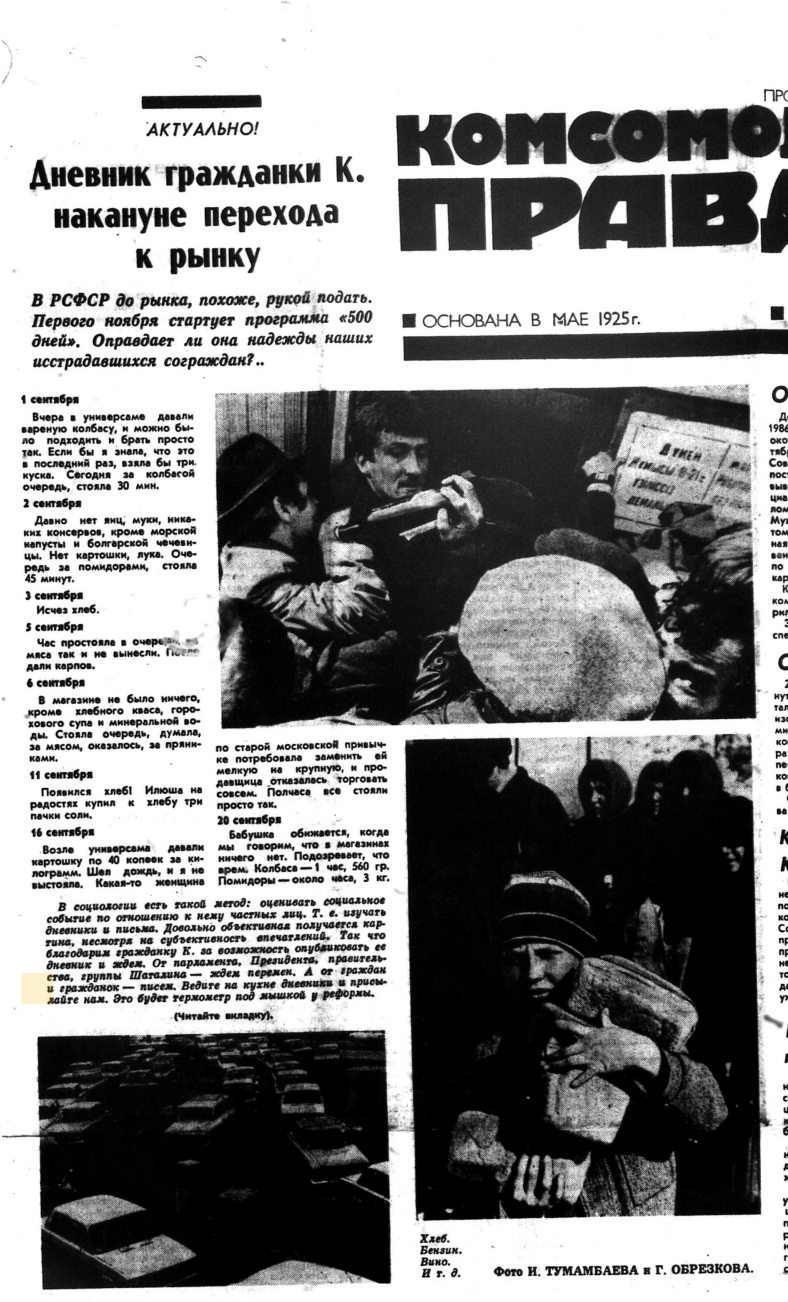

New! Diary of Citizen K. on the Eve of Transition to a Market Economy [Editor’s note:] In the RSFSR, a market economy seems just within reach. The “500 Days” program starts on November 1. Will it meet the hopes of our long-suffering fellow citizens? September 1 Yesterday at the universam (Soviet supermarket), they were giving out bologna sausage. You could just walk up and take some. If I’d known this would be the last time, I would have taken three. Today, there’s a line for sausage, and I waited for 30 minutes. September 2 There hasn’t been any eggs, flour, or canned goods for a long time, except for seaweed and Bulgarian lentils. No potatoes or onions. I stood in line for tomatoes for 45 minutes. September 3 Bread has disappeared. September 5 I stood in line for an hour, but they didn’t bring out any meat. Eventually, they handed out carp. September 6 The store had nothing except bread kvass, pea soup, and mineral water. There was a line, and I thought it was for meat, but it turned out to be for gingerbread. September 11 Bread has returned! In a fit of joy, Ilyusha bought three packets of salt to go with it. September 16 They were selling potatoes for 40 kopecks per kilogram near the universam. It was raining, so I wasn’t able to wait long enough to get any. One woman, in keeping with that old Moscow habit, demanded that her small potatoes be exchanged for larger ones. At that point, the saleswoman flat-out refused to sell anything. We’d all stood there for half an hour for nothing. September 20 Grandma gets upset when we say there’s nothing in the stores. She suspects us of lying. Sausage—1 hour wait for 560 grams. Tomatoes—about an hour for 3 kilograms. [Editor’s note]: In sociology, there’s a method of assessing a social event by the reactions of individuals to it—that is, by studying diaries and letters. This creates a fairly objective picture, despite the subjectivity of certain impressions. And so, we thank Citizen K. for allowing us to publish her diary… and now we wait. We’ll wait for change from Parliament, the President, the government, and from Shatalin’s group, but we’ll also wait for more letters from citizens. Keep diaries in your kitchens and send them to us. It will be a thermometer in the armpit of reform.

When Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022) was elected General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985, he inherited an economy that was still growing, albeit very slowly. His signature policy of perestroika, which he began promoting soon after assuming his post, aimed to improve Soviet economic capacity, but inadvertently created tougher economic times than citizens had faced in the years immediately preceding it. The only way out of the difficulties, Gorbachev’s team came to think, was to accept yet more economic challenges—which, though acute, would hopefully be short-lived.

In the fall of 1990, Gorbachev’s administration accordingly planned to implement economist Stanislav Shatalin’s (1934-1997) “500 Days” plan, which would hybridize the Soviet economy by introducing some market elements while retaining the overall framework of central planning. Ahead of implementing these changes, which proponents hoped would render the economy more robust, select Soviet press outlets worked in step with reformers to engage citizens in the process of economic hardship and transformation. In September 1990, a month before Shatalin’s plan was to be introduced, the editors of the Soviet daily Komsomolskaya pravda, which then enjoyed the largest readership in the country—that year, it set a new Guinness World Record for circulation—invited readers to document shortages and prices in their corner of the USSR through so-called “kitchen diaries,” which they were then encouraged to share as letters to the paper.

Editors published this call alongside an account by one “Citizen K.”, an example meant to provide guidance on how to keep a “kitchen diary.” K. noted how long she had to wait in line for sausage, the price of potatoes, and when bread disappeared and returned to the shelves. It is unclear if Citizen K. was a real person or if editors fabricated her diary for instructive purposes. Regardless, kitchen diaries and shortage letters became a veritable late-Soviet phenomenon, building on decades of similar letters from Soviet citizens to the state dating back at least to 1917. Perestroika-era calls for kitchen diaries, however, put a distinct spin on these citizen reports. Komsomolskaya pravda’s 29 September call for submissions termed these diaries “the thermometer under the armpit of reform,” underscoring the editors’ (and the state’s) desire for citizens to participate in the process of reform—in this case, by documenting the steep price austerity exacted for the government’s new economic initiatives.

In the fall of 1990, Gorbachev’s administration accordingly planned to implement economist Stanislav Shatalin’s (1934-1997) “500 Days” plan, which would hybridize the Soviet economy by introducing some market elements while retaining the overall framework of central planning. Ahead of implementing these changes, which proponents hoped would render the economy more robust, select Soviet press outlets worked in step with reformers to engage citizens in the process of economic hardship and transformation. In September 1990, a month before Shatalin’s plan was to be introduced, the editors of the Soviet daily Komsomolskaya pravda, which then enjoyed the largest readership in the country—that year, it set a new Guinness World Record for circulation—invited readers to document shortages and prices in their corner of the USSR through so-called “kitchen diaries,” which they were then encouraged to share as letters to the paper.

Editors published this call alongside an account by one “Citizen K.”, an example meant to provide guidance on how to keep a “kitchen diary.” K. noted how long she had to wait in line for sausage, the price of potatoes, and when bread disappeared and returned to the shelves. It is unclear if Citizen K. was a real person or if editors fabricated her diary for instructive purposes. Regardless, kitchen diaries and shortage letters became a veritable late-Soviet phenomenon, building on decades of similar letters from Soviet citizens to the state dating back at least to 1917. Perestroika-era calls for kitchen diaries, however, put a distinct spin on these citizen reports. Komsomolskaya pravda’s 29 September call for submissions termed these diaries “the thermometer under the armpit of reform,” underscoring the editors’ (and the state’s) desire for citizens to participate in the process of reform—in this case, by documenting the steep price austerity exacted for the government’s new economic initiatives.