Filed Under: Material culture > Arts or design > Kletchataia sumka, Chelnoki, and Ostap Bender

Kletchataia sumka, Chelnoki, and Ostap Bender

[2 items]

The checkered bag became a ubiquitous feature of train, bus, and ferry routes after the fall of the Soviet Union, especially on routes close to international borders. Light, cheap, and virtually indestructible, these polypropylene bags became the luggage of choice for a whole new class of merchants who, only a few years earlier, would have been guilty of the Soviet crime of “speculation.” Droves of entrepreneurs crossed borders to Finland, China, Poland, or wherever something—anything—might be cheaper or easier to acquire than in Russia. With checkered bags stuffed to gills, they would return by the same bus, train, or ferry to sell their goods in the local markets that had sprung up in every city and town throughout the former Soviet Union. The bags themselves became known as Bale Bags (sumka baul) or “Chelnok” Bags (sumka chelnoka), after the slang term for these new petty merchants.

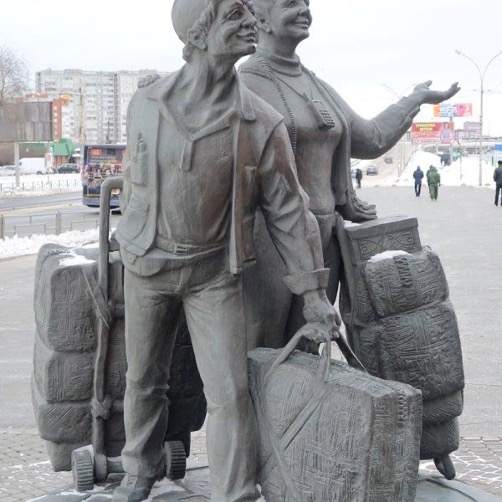

Chelnok, the diminutive of the archaic word chëln, meaning “boat,” also refers to the shuttle that is passed back and forth through the aperture or shed in loom weaving. In the 1990s, the word chelnok came to represent a petty merchant shuttling back and forth across a border, in effect weaving the sides closer together. Although the chelnoki earned more mockery than praise at the time, they did much of the heavy lifting that opened markets in the post-Soviet years. In 2009, Yekaterinburg even erected a monument to the chelnoki, which prominently features the checkered bag. The checkered bag was not just a post-Soviet Russian phenomenon, but became a commonplace object throughout the former Eastern Bloc.

Former Yugoslav author Dubravka Ugresic, for instance, suggests including it in her personal museum of state socialism: “It was just a plastic carry-all. What made it special was that it had red, white, and blue stripes. It was the cheapest piece of hand luggage on earth, a proletarian swipe at Vuitton. It zipped open and shut, but the zip always broke after a few days. […] the plastic bag with the red, white, and blue stripes made its way across East-Central Europe all the way to Russia and perhaps even farther—to India, China, America, all over the world. It is the poor man’s luggage, the luggage of petty thieves and black marketeers, of weekend wheeler-dealers, of the flea-market-and-launderette crowd, of refugees and the homeless. Oh, the jeans, the T-shirts, the coffee that traveled in those bags from Trieste to Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria […] The leather jackets and handbags and gloves leaving Istanbul and oddments leaving the Budapest Chinese market for Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia, Serbia, you name it. The plastic bags with the red, white, and blue stripes were nomads, they were refugees, they were homeless, but they were survivors, too: they rode trains with no ticket and crossed borders with no passport.”

Chelnok, the diminutive of the archaic word chëln, meaning “boat,” also refers to the shuttle that is passed back and forth through the aperture or shed in loom weaving. In the 1990s, the word chelnok came to represent a petty merchant shuttling back and forth across a border, in effect weaving the sides closer together. Although the chelnoki earned more mockery than praise at the time, they did much of the heavy lifting that opened markets in the post-Soviet years. In 2009, Yekaterinburg even erected a monument to the chelnoki, which prominently features the checkered bag. The checkered bag was not just a post-Soviet Russian phenomenon, but became a commonplace object throughout the former Eastern Bloc.

Former Yugoslav author Dubravka Ugresic, for instance, suggests including it in her personal museum of state socialism: “It was just a plastic carry-all. What made it special was that it had red, white, and blue stripes. It was the cheapest piece of hand luggage on earth, a proletarian swipe at Vuitton. It zipped open and shut, but the zip always broke after a few days. […] the plastic bag with the red, white, and blue stripes made its way across East-Central Europe all the way to Russia and perhaps even farther—to India, China, America, all over the world. It is the poor man’s luggage, the luggage of petty thieves and black marketeers, of weekend wheeler-dealers, of the flea-market-and-launderette crowd, of refugees and the homeless. Oh, the jeans, the T-shirts, the coffee that traveled in those bags from Trieste to Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria […] The leather jackets and handbags and gloves leaving Istanbul and oddments leaving the Budapest Chinese market for Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia, Serbia, you name it. The plastic bags with the red, white, and blue stripes were nomads, they were refugees, they were homeless, but they were survivors, too: they rode trains with no ticket and crossed borders with no passport.”