Filed Under: Video > Journalism > Marina Goldovskaya’s "Solovki Power" excavates painful historical memory

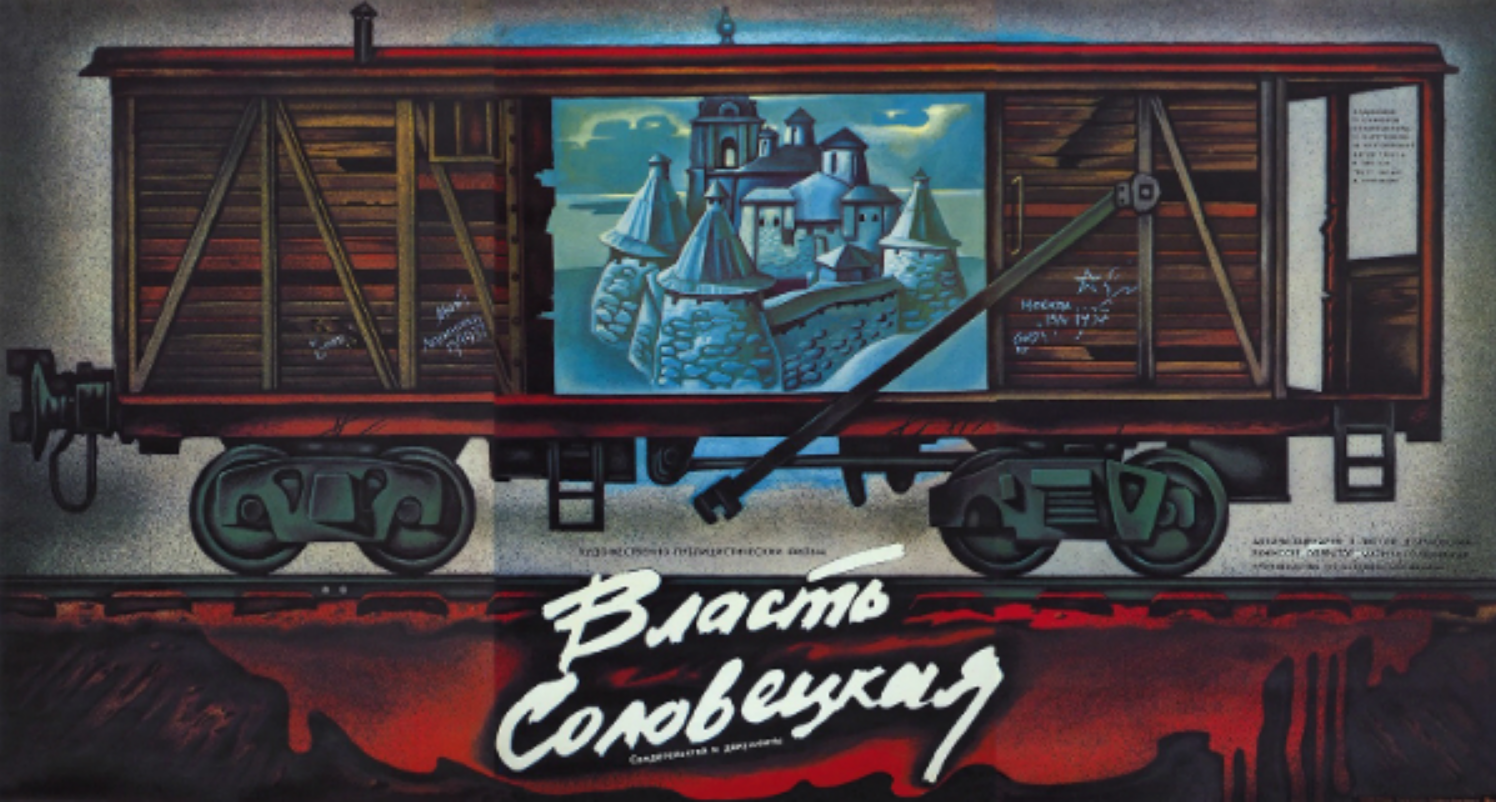

Marina Goldovskaya’s "Solovki Power" excavates painful historical memory

[2 items]

When he first announced the reform of glasnost or “openness” in 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev intended it to support the economic renaissance he envisioned for the Soviet Union. Yet the policy quickly transcended its original aim of “openness in the interests of socialism,” in Gorbachev’s phrase. Originally meant to encourage honesty about supply, production, and leadership issues the workplace, glasnost instead unleashed a torrent of memoirs, fiction publications, film releases, and topical commentary that collectively called into question the viability of the Soviet system as such. This period also saw the rise of a new kind of television that closely followed politics and performed unprecedented investigative journalism, seemingly heralding a new age of integrity in Soviet news. Besides illuminating current events, perestroika-era television helped bring to light previously suppressed elements of the Soviet past—most prominently, the history of Stalinist repressions.

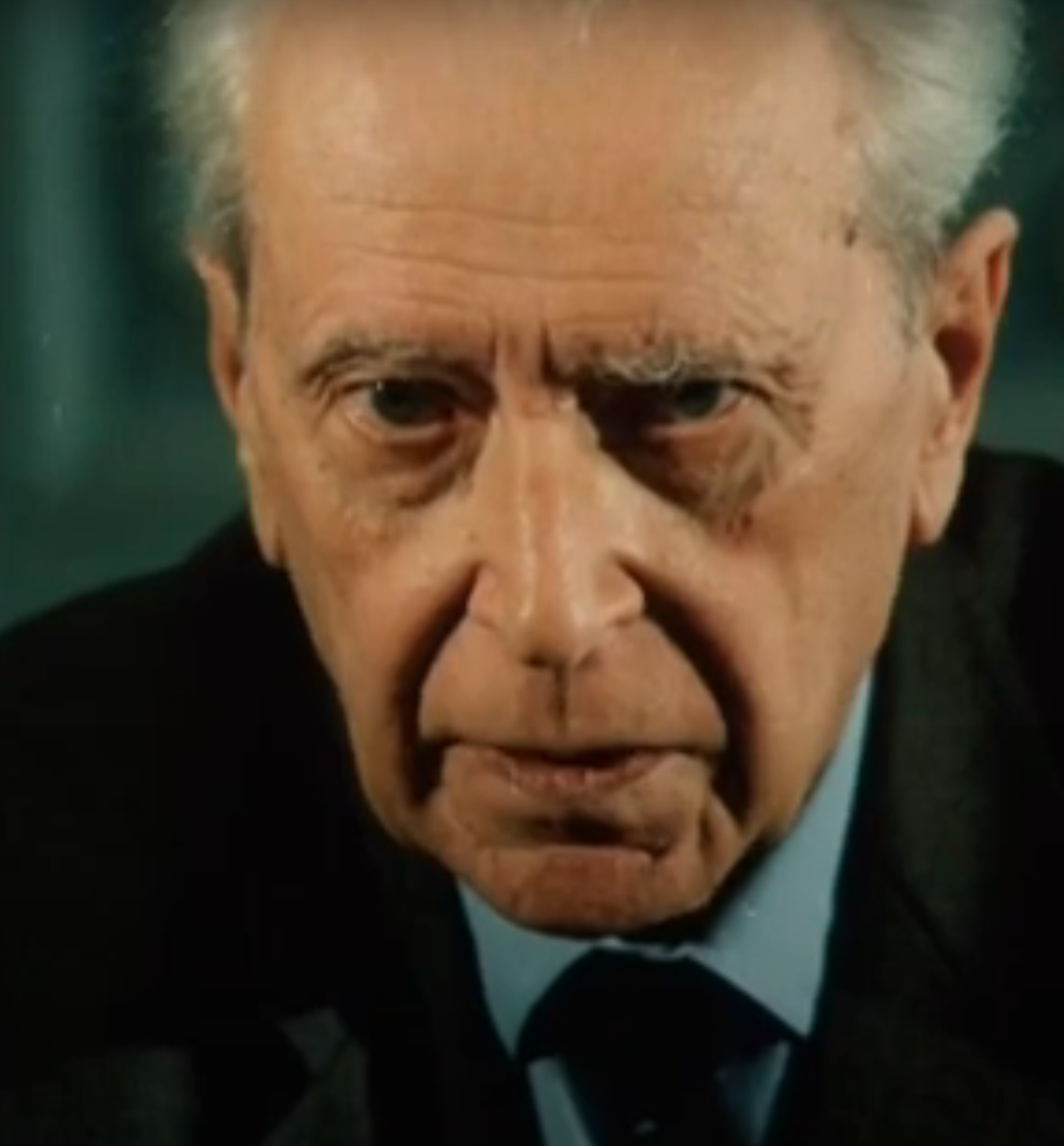

It was against this background that Marina Goldovskaya created her documentary about the oldest Soviet Gulag—founded under Lenin in 1923—located on the site of an ancient monastery on the Solovetsky Archipelago in the White Sea. Comprised of survivor testimony—especially by prominent member of the Soviet intelligentsia, the medievalist Dmitry Likhachev (seen in the second image above)—and characterized by the strong presence of Goldovskaya herself as narrator, the film treated the story of Solovki and its victims as a microcosm of Soviet existence. The film’s Russian title (Vlast’ solovetskaia) played on the close relationship between life in and outside the gulag, evoking both the phrase “Soviet power [vlast’ sovetskaia]” and a mocking rhyme long associated with the camp’s lawlessness and brutality: “Here rules not Soviet, but Solovetsk power [zdes’ vlast’ ne sovetskaia, zdes’ vlast’ solovetskaia].”

After a tortured path to release that included requests for changes from prominent Soviet officials (which Goldovskaya refused to implement), the film was finally approved for release in late 1988. As the scholar Erin Alpert writes, at the opening “in the Dom Kino film club in Moscow, the auditorium was packed. The protagonists came out on stage afterwards and received a standing ovation.” After its release to an unprecedented 300 movie theaters across the Soviet Union, the film became what Alpert calls “a memory vehicle of the glasnost era,” becoming the second most popular film of 1989 according to a fan survey conducted in the film magazine Sovetskii ekran (Soviet Screen).