Filed Under: Print > Journalism > "New Russians" at “Kommersant”

"New Russians" at “Kommersant”

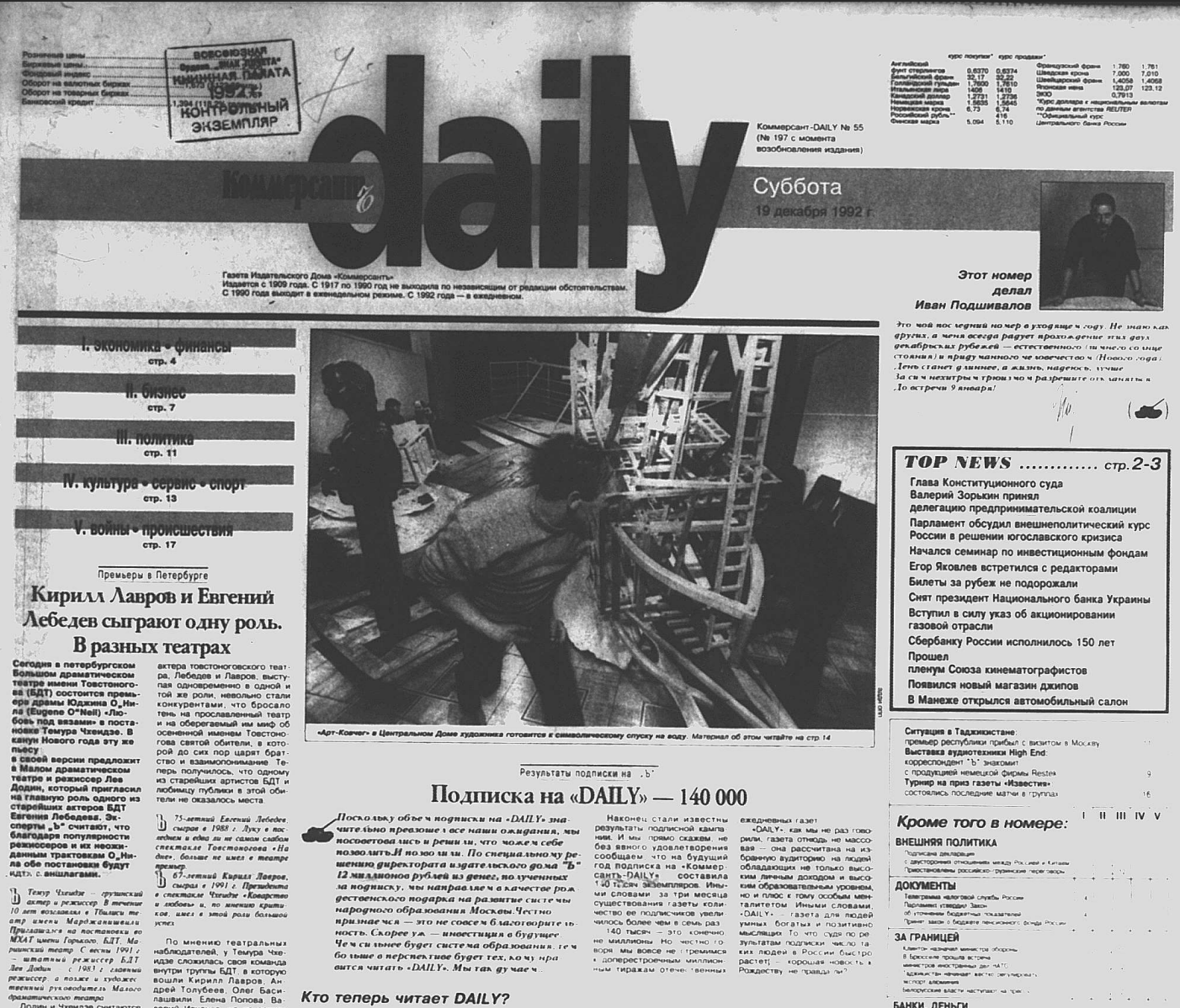

In September 1992, Russia’s first business weekly, Kommersant, inaugurated the pilot issue of Kommersant Daily— “daily” being written in Latin characters—with a “sociological” survey of their paper’s readership. The paper canvassed those who had agreed to subscribe to the Daily on the strength of an announcement in the Weekly that “emphasized the Daily’s high subscription price” of approximately 1400 rubles for six months (compared to 20 rubles for other nationally circulated newspapers at the time).

The survey showed that the bottom 85% of the proactive “New Russians” who had signed up for advance copies of Kommersant Daily made less than $1800 a month, with 23% of that group making less than $600 (by the end of 1992, many would be making half of that, due to hyperinflation). According to Kommersant’s calculations, these readers were comparable to the European middle class and constituted 2%-4% of Russia’s population. “Who are they?” the survey’s authors wondered. In fact, their questionnaire meant not so much to describe as to prescribe. Readers, per Kommersant, should think of themselves as a minoritarian, successful, morally justified elite. Hence, they were called upon to answer loaded questions meant to shape “New Russian” values in the paper’s own image.

The survey’s authors concluded that Kommersant’s readership was a “vanguard group [operezhaiushahia gruppa]” that inherited pre-Soviet “merchant” and “aristocratic” estates, even as 71% of them were classified as the “second-generation intellectual” grandchildren of proletarians, themselves educated in Soviet institutions. According to the results of Kommersant’s survey, “New Russians” work hard, do not emigrate, are self-made, take risks “even if the chances [of success] do not seem good,” and do not especially value “morality [nravstvennost’],” “prosperity,” or “power over others.” Half of respondents believed that, “in the eyes of the [general] population, they are gangsters and freeloaders.” Only 2% hoped to “be seen as heroes.” Almost all stated that “Russia is gradually becoming a normal European country.”

Three months later, around Western Christmastime, Kommersant celebrated “140,000 subscriptions” to the Daily, writing that this publication “is designed not for the masses, but for a selective audience: people not only with a high income and an education, but also those with a special mentality.” That is, the Daily positioned itself as a paper for “smart, rich, positively disposed people.” Given their growing subscription numbers, the snippet concludes, “the ranks of such people are rapidly growing in Russia,” which is “good news for Christmas, is it not?”

Few outside Kommersant’s editorial offices thought of “New Russians” in positive terms. In early 1990s jokelore, the moniker referred to goons in fancy cars, while the Western press recognized “New Russians” by their raspberry-colored Armani suits, their knock-off Turkish leather, and their shady business dealings, which seemed mostly to involve “the export of natural resources, playing on the currency exchange rates, and other financial operations,” as Kommersant’s editors quoted from Newsweek on 13 February 1993. The editors responded to this uncharitable Western perception with a disdainful note: “In the view of the experts at Kommersant, this portrait of New Russians […] looks more like an unsuccessful caricature. It has as much to do with true ‘New Russians’ as the image of a fat capitalist with a cigar in his teeth does with Henry Ford.”

The survey showed that the bottom 85% of the proactive “New Russians” who had signed up for advance copies of Kommersant Daily made less than $1800 a month, with 23% of that group making less than $600 (by the end of 1992, many would be making half of that, due to hyperinflation). According to Kommersant’s calculations, these readers were comparable to the European middle class and constituted 2%-4% of Russia’s population. “Who are they?” the survey’s authors wondered. In fact, their questionnaire meant not so much to describe as to prescribe. Readers, per Kommersant, should think of themselves as a minoritarian, successful, morally justified elite. Hence, they were called upon to answer loaded questions meant to shape “New Russian” values in the paper’s own image.

The survey’s authors concluded that Kommersant’s readership was a “vanguard group [operezhaiushahia gruppa]” that inherited pre-Soviet “merchant” and “aristocratic” estates, even as 71% of them were classified as the “second-generation intellectual” grandchildren of proletarians, themselves educated in Soviet institutions. According to the results of Kommersant’s survey, “New Russians” work hard, do not emigrate, are self-made, take risks “even if the chances [of success] do not seem good,” and do not especially value “morality [nravstvennost’],” “prosperity,” or “power over others.” Half of respondents believed that, “in the eyes of the [general] population, they are gangsters and freeloaders.” Only 2% hoped to “be seen as heroes.” Almost all stated that “Russia is gradually becoming a normal European country.”

Three months later, around Western Christmastime, Kommersant celebrated “140,000 subscriptions” to the Daily, writing that this publication “is designed not for the masses, but for a selective audience: people not only with a high income and an education, but also those with a special mentality.” That is, the Daily positioned itself as a paper for “smart, rich, positively disposed people.” Given their growing subscription numbers, the snippet concludes, “the ranks of such people are rapidly growing in Russia,” which is “good news for Christmas, is it not?”

Few outside Kommersant’s editorial offices thought of “New Russians” in positive terms. In early 1990s jokelore, the moniker referred to goons in fancy cars, while the Western press recognized “New Russians” by their raspberry-colored Armani suits, their knock-off Turkish leather, and their shady business dealings, which seemed mostly to involve “the export of natural resources, playing on the currency exchange rates, and other financial operations,” as Kommersant’s editors quoted from Newsweek on 13 February 1993. The editors responded to this uncharitable Western perception with a disdainful note: “In the view of the experts at Kommersant, this portrait of New Russians […] looks more like an unsuccessful caricature. It has as much to do with true ‘New Russians’ as the image of a fat capitalist with a cigar in his teeth does with Henry Ford.”