Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Novyi Vzgliad: Violence, Political Irony, and National Pride

Novyi Vzgliad: Violence, Political Irony, and National Pride

[4 items]

Initially conceived as an extension of the popular TV show Vzgliad (View or Glance), Novyi vzgliad (New view) was founded by Evgeny Dodolev (1957-). A former correspondent of Sovershenno sekretno (Top secret), Dodolev brought aboard that publication’s penchant for combining journalistic transparency with sensationalism and political irony. In terms of sensationalism—that is, sex, violence, and true crime—Novyi vzgliad tended to one-up its predecessors with headlines like “Boobs Coated in Flour”; “The Cannibal-Lover”; “Serial Murders”; and “Uxoricides.” The biweekly magazine soon became associated with new forms of political irony and famous for the fierce debates taking place in its pages—debates that sometimes resulted in very public trials.

In accordance with its slogan of “total pluralism,” the magazine made a point of publishing completely opposite views side-by-side. An issue could feature, for instance, the Stalinist, ultranationalist essentialism of Aleksandr Prokhanov, “the nightingale of the army headquarters [solovei genshtaba]” counterbalanced by the hyper-liberal, anti-Russian essentialism of the magazine’s self-defined “main political extremist,” former dissident Valeriya Novodvorskaya (1950-2014). Two of Novyi vzgliad’s contributors in particular—the provocative émigré writer Eduard Limonov (1943-2020) and the poet, journalist, and queer multimedia artist Yaroslav (Slava) Mogutin (1974-)— discoursed on violence, sexuality, and transgression as part of a new, paradoxical conception of politics and national identity.

Mogutin, for his part, helped define Novyi vzgliad’s style as a combination of tabloid-like sensationalism and “total pluralism.” One of the first openly gay public figures in Russia, he was also among the first authors who made writing about his sexuality, and about homosexuality in general, central to his work. His public persona mixed irony and defiance, anti-intellectualism, Russian nationalism, and a fascination with youth and raw, aggressive masculinity as incarnated in hard-bodied young soldiers and lumpenproletarians. As part of a 1994 art performance, he publicly celebrated and tried to register his marriage to his male partner, the American artist Robert Filippini. That same year, Mogutin faced prosecution for a fervently pro-Russian and vehemently anti-Chechen article, “The Chechen Knot,” which he wrote in response to the First Chechen War (1994-1996). He was ultimately forced to emigrate to the United States, where he has lived ever since.

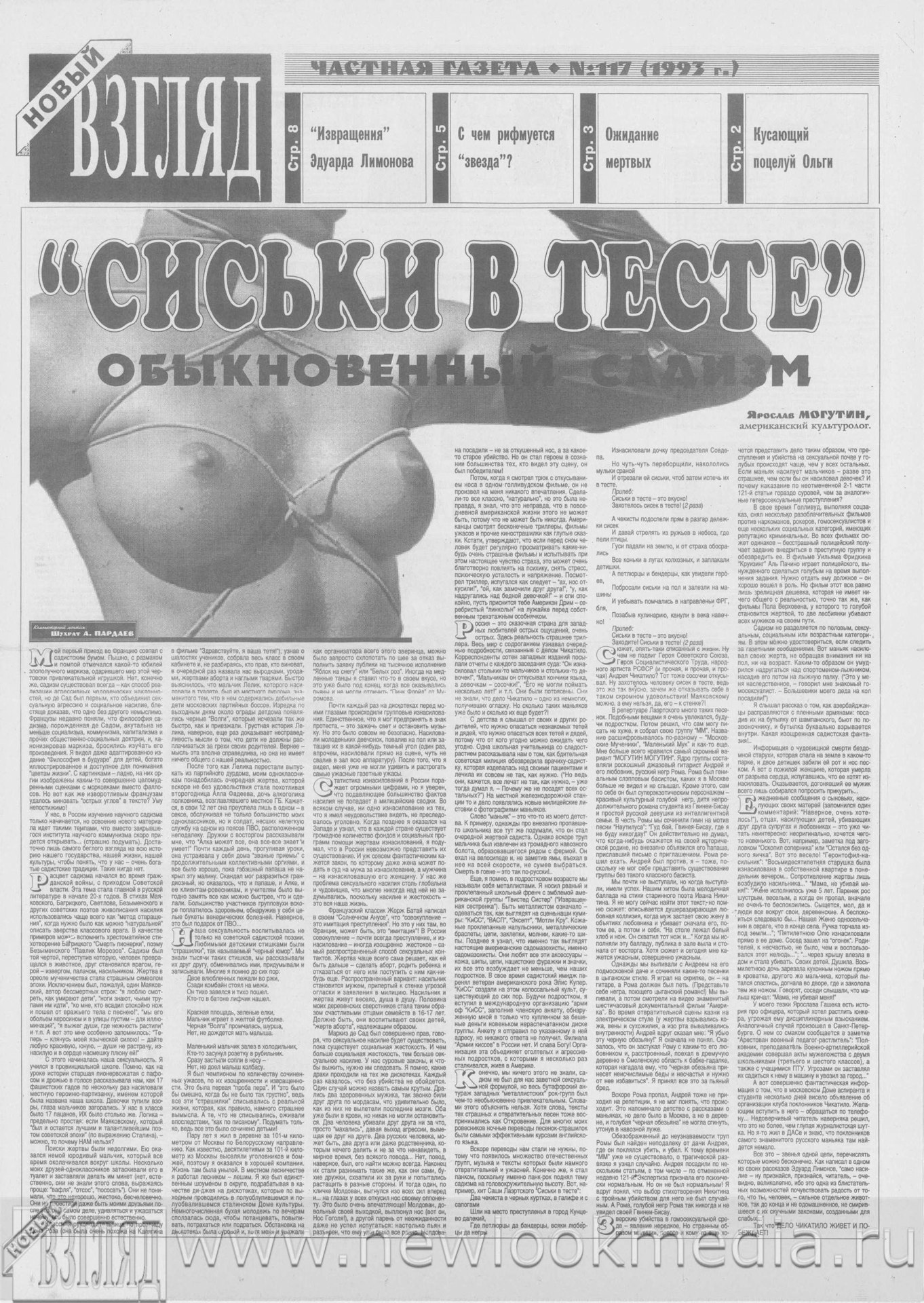

In the article selected here (images 2 and 3 above), “Boobs Coated in Flour,” Mogutin claimed that violence and sadism—in the form of rape, cannibalism, and serial killing—were essential components of Russia’s everyday life, literature, and identity and of his own generation’s relationship with sex. As he did in “The Chechen Knot,” Mogutin combined a (self-)critical attitude toward these pervasive horrors and the “lack of boundaries” they represented with ironic pride in his country’s seeming descent into barbarism. Mogutin’s piece and the style of Novyi vzgliad more generally demonstrate how early post-Soviet stiob, or parody based on overidentification, became increasingly associated with a darkly ironic politics. The result is a kind of “shimmering” political style that has since become pervasive in the Putin era among both pro-government and oppositional actors. At the same time, in Mogutin’s work, the moral unmasking (razoblachenie) that characterized perestroika-era chernukha or gore transforms into a paradoxical form of national pride—a sense of belonging and identity seemingly connected with the experience of violence itself.

In accordance with its slogan of “total pluralism,” the magazine made a point of publishing completely opposite views side-by-side. An issue could feature, for instance, the Stalinist, ultranationalist essentialism of Aleksandr Prokhanov, “the nightingale of the army headquarters [solovei genshtaba]” counterbalanced by the hyper-liberal, anti-Russian essentialism of the magazine’s self-defined “main political extremist,” former dissident Valeriya Novodvorskaya (1950-2014). Two of Novyi vzgliad’s contributors in particular—the provocative émigré writer Eduard Limonov (1943-2020) and the poet, journalist, and queer multimedia artist Yaroslav (Slava) Mogutin (1974-)— discoursed on violence, sexuality, and transgression as part of a new, paradoxical conception of politics and national identity.

Mogutin, for his part, helped define Novyi vzgliad’s style as a combination of tabloid-like sensationalism and “total pluralism.” One of the first openly gay public figures in Russia, he was also among the first authors who made writing about his sexuality, and about homosexuality in general, central to his work. His public persona mixed irony and defiance, anti-intellectualism, Russian nationalism, and a fascination with youth and raw, aggressive masculinity as incarnated in hard-bodied young soldiers and lumpenproletarians. As part of a 1994 art performance, he publicly celebrated and tried to register his marriage to his male partner, the American artist Robert Filippini. That same year, Mogutin faced prosecution for a fervently pro-Russian and vehemently anti-Chechen article, “The Chechen Knot,” which he wrote in response to the First Chechen War (1994-1996). He was ultimately forced to emigrate to the United States, where he has lived ever since.

In the article selected here (images 2 and 3 above), “Boobs Coated in Flour,” Mogutin claimed that violence and sadism—in the form of rape, cannibalism, and serial killing—were essential components of Russia’s everyday life, literature, and identity and of his own generation’s relationship with sex. As he did in “The Chechen Knot,” Mogutin combined a (self-)critical attitude toward these pervasive horrors and the “lack of boundaries” they represented with ironic pride in his country’s seeming descent into barbarism. Mogutin’s piece and the style of Novyi vzgliad more generally demonstrate how early post-Soviet stiob, or parody based on overidentification, became increasingly associated with a darkly ironic politics. The result is a kind of “shimmering” political style that has since become pervasive in the Putin era among both pro-government and oppositional actors. At the same time, in Mogutin’s work, the moral unmasking (razoblachenie) that characterized perestroika-era chernukha or gore transforms into a paradoxical form of national pride—a sense of belonging and identity seemingly connected with the experience of violence itself.