Philosophy at the Margins

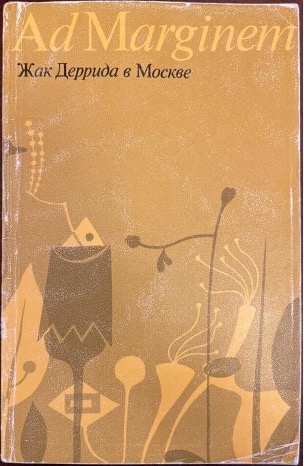

Cover of Jacques Derrida in Moscow (1993), an early volume in the Philosophy on the Margins series from Ad Marginem publishers (1992–95)

Jacques Derrida in Moscow.

Beginning in October 1992, one of the thousands of new private publishers operating in post-Soviet Russia distinguished itself by taking on an ambitious and erudite project: in its own words, an “international collection of contemporary thought.” At a time when much of the book market was moving towards genre fiction and pulp potboilers, Ad Marginem’s “Philosophy at the Margins” volumes brought together difficult and provocative theoretical texts from around the world. The series sought to “bring its reader into the circle of the most pressing questions of contemporary philosophy and cultural studies, to help overcome the increasingly obvious deficit in humanistic information, and to resurrect a fully functioning dialogue with Western philosophical thought,” according to the description printed in each volume.

Claiming to be the first “experiment in publishing an international philosophical book series” in Russia, Ad Marginem’s offerings aspired to nothing less than “uniting the efforts of domestic and Western researchers to create an international intellectual community” that would come together at seminars and conferences and eventually put out an “international journal or contemporary thought called Ad Marginem.” Although the journal never came to fruition, the head of the publishing house, Alexander Ivanov, managed to bring together a star-studded editorial board that included Susan Buck-Morss, Fredric Jameson, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Derrida, Félix Guattari, Merab Mamardashvili, and many others. Together, they put out at least 15 volumes from writers as diverse as the Marquis de Sade, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Elias Canetti, and others. The series was hugely influential in bringing contemporary continental philosophy—especially French postwar thought—to Russia and placing it in immediate, local context.

One striking example is the volume Jacques Derrida in Moscow (1993), seen above, which collects a series of fragments the philosopher wrote during, and in response to, his 1990 visit to the Russian capital. It is framed by a foreword and commentary by Russian philosopher Mikhail Ryklin, who noted that, for the first time, a text by Derrida had found its first publication in Russian. Furthermore, since there were no plans for publication in French, this translation would “function as the original”—playing with priorities and undermining the very concept of an authentic original in a manner that, according to Ryklin, might have pleased Derrida himself. Derrida’s fragments continue the play with originals and translations. Titled, in English (and riffing on the 1968 Beatles song) “Back from Moscow, in the USSR,” the notes recount—among reflections on René Étiemble, André Gide, and Walter Benjamin—an intriguing conversation with Moscow interlocutors who tell Derrida that “the best translation for perestroika, the translation that they used among themselves, is ‘deconstruction.’” A Soviet colleague, he claims, even said to him, “Deconstruction? That’s today’s USSR.”

Claiming to be the first “experiment in publishing an international philosophical book series” in Russia, Ad Marginem’s offerings aspired to nothing less than “uniting the efforts of domestic and Western researchers to create an international intellectual community” that would come together at seminars and conferences and eventually put out an “international journal or contemporary thought called Ad Marginem.” Although the journal never came to fruition, the head of the publishing house, Alexander Ivanov, managed to bring together a star-studded editorial board that included Susan Buck-Morss, Fredric Jameson, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Derrida, Félix Guattari, Merab Mamardashvili, and many others. Together, they put out at least 15 volumes from writers as diverse as the Marquis de Sade, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Georges Bataille, Elias Canetti, and others. The series was hugely influential in bringing contemporary continental philosophy—especially French postwar thought—to Russia and placing it in immediate, local context.

One striking example is the volume Jacques Derrida in Moscow (1993), seen above, which collects a series of fragments the philosopher wrote during, and in response to, his 1990 visit to the Russian capital. It is framed by a foreword and commentary by Russian philosopher Mikhail Ryklin, who noted that, for the first time, a text by Derrida had found its first publication in Russian. Furthermore, since there were no plans for publication in French, this translation would “function as the original”—playing with priorities and undermining the very concept of an authentic original in a manner that, according to Ryklin, might have pleased Derrida himself. Derrida’s fragments continue the play with originals and translations. Titled, in English (and riffing on the 1968 Beatles song) “Back from Moscow, in the USSR,” the notes recount—among reflections on René Étiemble, André Gide, and Walter Benjamin—an intriguing conversation with Moscow interlocutors who tell Derrida that “the best translation for perestroika, the translation that they used among themselves, is ‘deconstruction.’” A Soviet colleague, he claims, even said to him, “Deconstruction? That’s today’s USSR.”