Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Romantics and Fascists

Romantics and Fascists

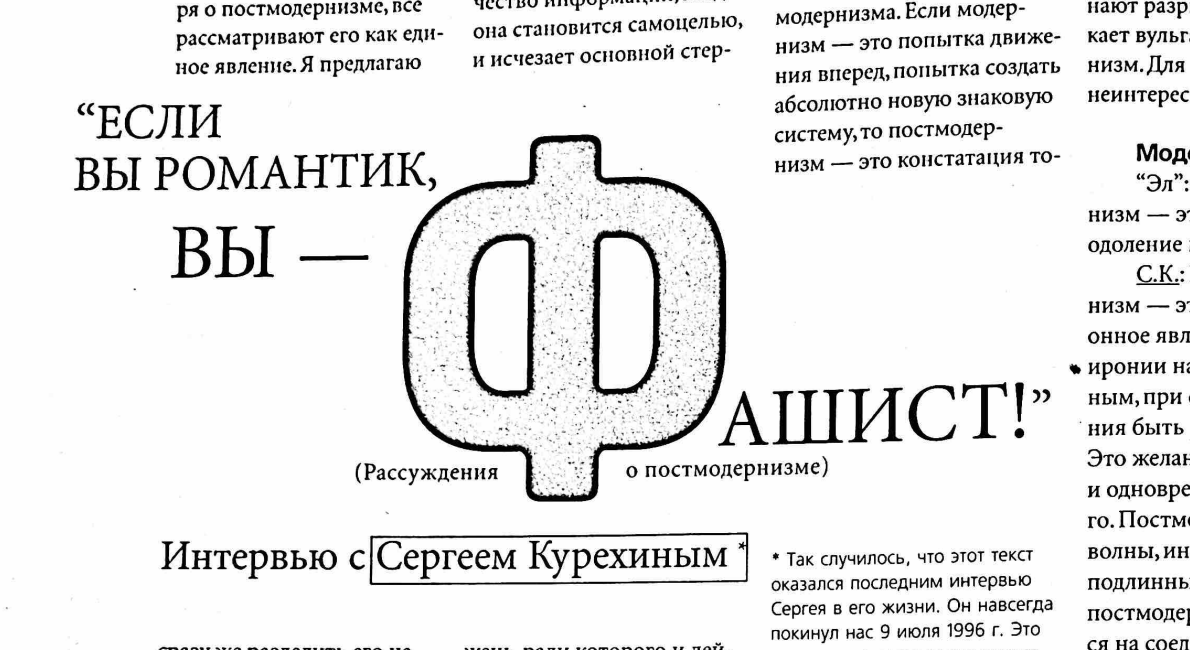

"If you're a romantic, then you're [necessarily] a fascist!"

Discourses surrounding identity and chernukha (gore) in the nascent post-Soviet mediascape reflect an underlying dialectical tension between virtual reality and manipulation, on the one hand, and the authenticity of physical experience and true belief, on the other. A perfect example of this problematics is the experimental musician and performer Sergey Kuryokhin (1954-1996), who famously argued that Lenin was a mushroom on Soviet television in the spring of 1991 and was the quintessential postmodern artist and practitioner of the specific late-Soviet form of irony known as stiob.

Kuryokhin was fascinated with totalitarian artforms, in the sense of artforms or actions that involved a radical transformation of reality. This position explains both his interest in mass manipulation and his romantic impulse toward sincerity, belief, and absolute commitment. After dabbling in musical performance, film, radio, and television, Kuryokhin decided “to experiment with radical politics,” as he put it, by joining the National Bolshevik Party, the radical organization led by Eduard Limonov (1943-2020) and Alexander Dugin (1962-). He also helped organize Dugin’s campaign for a seat in the Russian Duma in 1995.

In an interview with Dugin’s far-right publication Elementy (the interviewer was, in all likelihood, Dugin himself), Kuryokhin elaborated on the tension between belief and the postmodern commodification and “virtualization” of reality that arose after the fall of the Soviet Union. Kuryokhin conceived of belief as the antidote to virtualization. In the interview, he distinguished between a “vulgar” postmodernism and its authentic, “elitist” counterpart: “[These epigones] represent a cheap kind of postmodernism, embodied in the ultimate mass artform: television. All shows try to be sarcastic (obstebat’sia), nobody wants to talk about anything serious…It is no coincidence that the phrase ‘as if’ (kak by) is so common today—it signals that people are unable to take their own words seriously.” In contrast, an “authentic postmodernist” could “joke about the revolution while maintaining the desire to be revolutionary.” In this understanding, fascism is a radical form of romanticism or the quintessential form of militancy, precisely in the sense of total commitment to an artistic or political vision. For Kuryokhin, if one is a romantic—that is, truly committed to an aesthetic vision—one will inevitably “become a fascist.”

Kuryokhin was fascinated with totalitarian artforms, in the sense of artforms or actions that involved a radical transformation of reality. This position explains both his interest in mass manipulation and his romantic impulse toward sincerity, belief, and absolute commitment. After dabbling in musical performance, film, radio, and television, Kuryokhin decided “to experiment with radical politics,” as he put it, by joining the National Bolshevik Party, the radical organization led by Eduard Limonov (1943-2020) and Alexander Dugin (1962-). He also helped organize Dugin’s campaign for a seat in the Russian Duma in 1995.

In an interview with Dugin’s far-right publication Elementy (the interviewer was, in all likelihood, Dugin himself), Kuryokhin elaborated on the tension between belief and the postmodern commodification and “virtualization” of reality that arose after the fall of the Soviet Union. Kuryokhin conceived of belief as the antidote to virtualization. In the interview, he distinguished between a “vulgar” postmodernism and its authentic, “elitist” counterpart: “[These epigones] represent a cheap kind of postmodernism, embodied in the ultimate mass artform: television. All shows try to be sarcastic (obstebat’sia), nobody wants to talk about anything serious…It is no coincidence that the phrase ‘as if’ (kak by) is so common today—it signals that people are unable to take their own words seriously.” In contrast, an “authentic postmodernist” could “joke about the revolution while maintaining the desire to be revolutionary.” In this understanding, fascism is a radical form of romanticism or the quintessential form of militancy, precisely in the sense of total commitment to an artistic or political vision. For Kuryokhin, if one is a romantic—that is, truly committed to an aesthetic vision—one will inevitably “become a fascist.”