Filed Under: Print > Visual arts > Shaburov Sasha Christ

Shaburov Sasha Christ

[2 items]

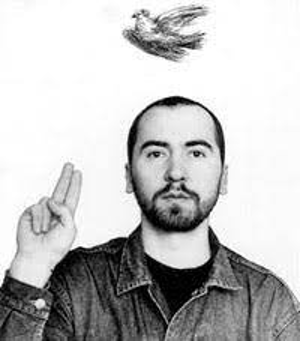

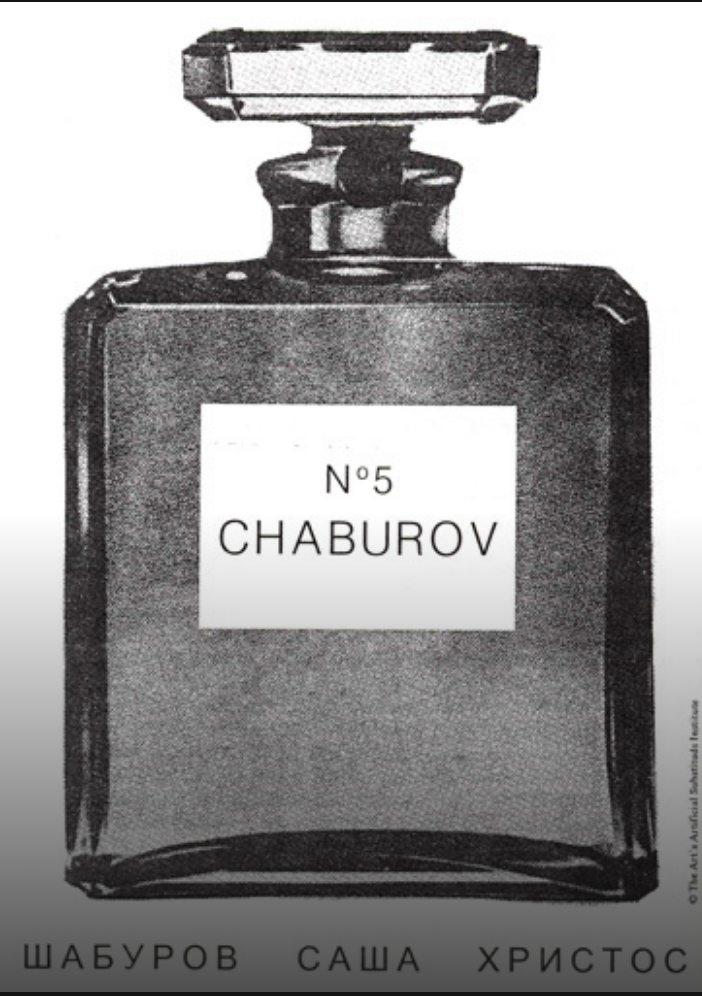

Artist Alexander Shaburov’s (1965-) project in the 1990s consisted of repeated efforts to engage and incorporate Russian daily life into “proper,” Western-style contemporary art. Shaburov Sasha Christ (1995) involved the production of thirty posters appropriating a variety of imagery, from advertising for Chanel’s No. 5 perfume to promotions for a new religious (?) cult, which he then distributed to strangers. The title of the piece plays with the wording of an omnipresent poster advertising a cult lead by self-proclaimed messiah Marina Tsvigun. Known as the Great White Brotherhood of YUSMALOS, this cult attempted to forcibly seize the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv in 1993, with members handing out leaflets calling the cult leader “Maria Devi Christ,” combining multiple divinities from both Western and Eastern religious traditions in Tsvigun’s person.

Shaburov’s posters usurp the self-glorifying mode of a 1990s-era Russian cult, or a Western perfume ad, while purposefully marking it as a sign of inadequacy. An accompanying text states that “becoming a ‘great artist’ in the provinces is possible only in the role of the ‘little person,’” with the performer forced to “[museum-ize] the minutiae of his daily life as the only unique things he possesses.” Attempts to transform the daily life and implausible ambitions of the provincial “little person” into an appropriate subject for contemporary art dominate Shaburov’s projects in the 1990s. For instance, in Filling and Fitting Teeth (1998), Shaburov applied to the George Soros Fund for an artistic grant. When he received the money, he used it to finally visit the dentist—documenting the resulting prolonged dental work as a kind of performance art. In The Ways Some Will Die (1998), Shaburov wrote out the deaths he imagined for his friends and acquaintances. He then staged a grandiose burial service and funeral for himself as a premature and ludicrous summary of the artist’s life well-lived—and a memorial to unrealized artistic projects.

Shaburov’s work responds to the changing situation for post-Soviet artists by embracing the myths of the Western art market with virulent irony and laughter. His critique plays with the marginal status of artists, especially provincial ones, in the post-Soviet world, relying on provocative appropriations and deconstructions of Western artistic clichés and archetypes to construct an artist-myth appropriate to the new epoch.