TaMtAm Rock Club documentary for German television (1993)

[5 items]

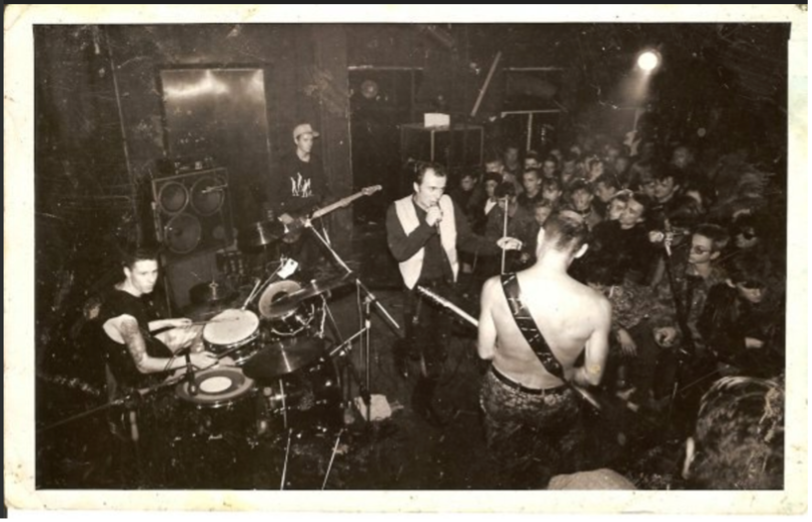

TaMtAm—the first and, until 1994, only Western-style rock club in Russia—existed from 1991 to 1996. Cellist Vsevolod (Seva) Gakkel (1953-), of the Leningrad-based band Akvarium, was inspired to establish it after visiting the famous CBGB (1973-2006) in New York City. TaMtAm, like CBGB during some of its history, specialized in punk rock, providing the budding underground punk scene in Russia with cultural legitimacy as well as a much-needed performance venue.

Some have accused Gakkel’s establishment of breeding far-right Russian nationalism among youth subcultures or, at least, providing it a physical organizational platform in the early 1990s. The documentary excerpted here, instead, testifies to the transnational nature of punk after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991. Shot for German television in 1993, the self-titled film depicted a live music industry in flux amid the breakneck privatization drives of the first post-Soviet years. The documentary lays bare evidence of the rapid inflation that would define Russian life in the early 1990s: club patrons can be seen paying for entry with 100 ruble bills; alcohol is readily available for purchase; and privately commissioned bouncers have replaced Soviet police as guardians of the peace. Like the economy and the law, the production and consumption of underground popular music changed rapidly following Soviet collapse.

The film also spotlights key figures from the underground punk scene in post-Soviet St. Petersburg. In addition to Gakkel, who appears throughout the film, the footage includes Russian rock-music historian Andrei Burlaka (1965-), who peeks into the frame to ask a performer if he is giving an interview. Also prominently featured is Andrei “The Nose” Kuzmin, lead vocalist of the seminal punk band Pupsy. In the surprisingly early year of 1991, Pupsy went on a European tour through Britain and Germany, organized by the guest vocalist Princess Katya Golitsyna, a London-born descendant of the Russian nobility, when she lived and studied in Russia.

Much of the film is comprised of a prominent display of tattoos and body art modeled by TaMtAm performers and their fans. Late-Soviet punk rock fashion choices, replete with mohawks and shaved hairstyles, show the changing self-presentation of post-Soviet youth. Meanwhile, the club’s linguistic and social makeup is also distinctly diversified compared to Soviet times courtesy of an international lineup, Russian bands performing songs in English, and Anglophone and Francophone patrons presented as club regulars. At the time the documentary was filmed, TaMtAm represented the opening of borders and the rapid obsolescence of the Iron Curtain in a new, seemingly westward-looking era of Russian history.