Filed Under: Print > Journalism > The Chechen Knot: 13 theses.

The Chechen Knot: 13 theses.

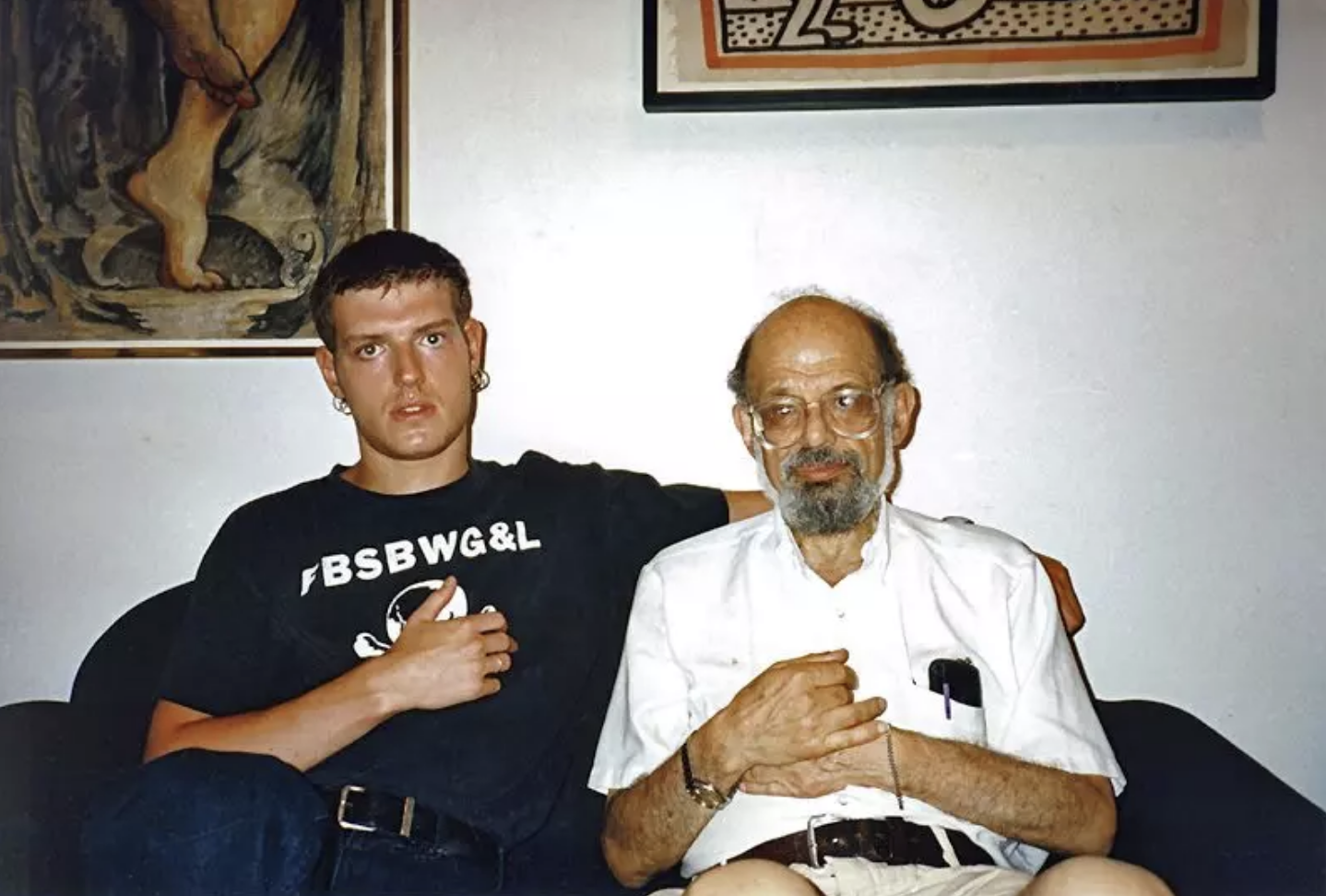

Slava Mogutin with beat poet Allen Ginsberg in 1995

THE CHECHEN KNOT: 13 THESES

1. Back to the yurts!

From numerous TV reports, we can see that the so-called Chechen Republic has a typical Soviet landscape. Russian names: café "Minutka" and others. This area became civilized thanks to Russians; conditions appeared in which one could live like a human being, not like the Chechens lived before the Russians. This is a semi-wild, barbaric nation, famous only for its barbarism and gloomy ferocity, having given the world absolutely nothing except international terrorism and drug trafficking.

It wasn't we who needed them, but they who needed us. They want to live independently from Russia? Let them relocate to their villages, kishlaks, mountain gorges and live in yurts, tents, caves, dugouts or whatever they have, and defecate where they eat! Let them! But only provided that it's not Russian territory, inhabited and developed by Russians and with Russian money, and where half the population is Russian.

2. There's no need to create an enemy. He already exists.

The Russian-Chechen conflict didn't arise today or yesterday. It's not the "Chechen mafia," which terrorized Moscow, that's responsible for the fact that Chechens were, are, and will be enemy №1 among so-called "people of Caucasian nationality" for Russians. Take Russian classics with their high morality, and there the "evil Chechen" is the enemy. Ask any Russian what feelings he experiences toward Chechens, to understand that the hatred here is not ideological or rational in nature – it's deeper, much deeper: zoological, genetic, animal. Ethnic incompatibility.

3. Propaganda isn't at zero. Propaganda is in the negative.

When Americans need to land in Haiti, strike Iraq or the positions of Bosnian Serbs, actions of this kind are always justified by interests of national and world security; any territory is easily declared a "zone of strategic interests for the USA" – and full speed ahead! The propaganda machine works at full throttle. To convince the whole world of the righteousness of your actions, you need to be supported at least by citizens of your own country.

Our talentless ideologues of "democracy" are unable to secure such support even now, when it's not about world domination (far from it, that's long been given up!), not about some abstract "strategic interests" ("survival first, luxuries later!") – but about the concrete integrity of the state.

4. The "creative intelligentsia" is an anti-Russian cesspool.

It's known that during the Vietnam War, more than unpopular among Americans, the combat spirit of American soldiers was raised by world-class stars, among whom was Marilyn Monroe. The great Marlene Dietrich performed many times for the troops of the anti-Hitler coalition on the fronts of World War II. Indeed, it would seem, especially when "the cannons speak" – "the muses" should not be silent. This is both an opportunity to show one's civic position, one's patriotism, and good publicity, which didn't hurt even such stars.

Why shouldn't Pugacheva with Kirkorov or whoever else is around go with concerts to Chechnya and support the morale of Russian soldiers? Why shouldn't artists from variety shows, theater and cinema, poets, musicians gather in such a frontline concert brigade, as in the Great Patriotic War?

However, our immoral, half-decayed "creative intelligentsia" in its eternal anti-Russian, anti-patriotic frenzy is ready to justify any crimes against Russia and against Russians. Licking authority, whatever it may be, writing denunciations, collective letters demanding to "crush the vermin" – that's fine, but demonstrating genuine patriotism they don't want and can't, and don't even bother themselves with it.

5. Moscow and Muscovites. The end of the philistine world.

In October '93, war was in the center of Moscow, a war of the anti-people government against its own people, a war supported and approved by the West, a war in which hundreds of Russians also died. The majority of Muscovites, like rats or rabbits, sat in their homes. The philistines wanted to preserve peace and quiet in their burrows and were ready to forgive any murders and crimes, as long as they weren't the victims. They were further ready to endure any reforms, any obese Gaidars on their necks, just to preserve their petty-bourgeois, philistine world.

Moreover, in moments of danger, Moscow resembles an ostrich, burying its head in the sand so as not to see anything happening around. The thick-skinned Muscovites are ready, for the sake of their own momentary well-being, to agree that Russia's borders should be reduced to the size of the Moscow region.

The Chechen war became the collapse of the philistine world. War entered every home and forced everyone to "take a stand": either you're for or against, either you're for Russia or you're against it, either you're Russian, with Russians and for Russians – or you're for them, for the Chechens. The acute sense of real danger hanging over the entire country finally awakened in the fat Moscow rabbits, rats, and ostriches their weakened national self-consciousness.

6. The war for Chechnya is a war for Russia.

Chechnya is a part of Russia; it was, is, and will be Russian territory. Everything happening in Chechnya is Russia's internal affair. However, this conflict cannot be called local. Too many want to use the situation as an opportunity to stand against Russians. It's now well-known that besides powerful Muslim support, Dudayev's cutthroats have as allies Afghan mujahideen, Ukrainian nationalists, and even a female gang of Baltic snipers, "White Tights" (apparently, their own men don't satisfy them at all). This unequivocally testifies that the war for Chechen independence is a war against Russia, uniting all her enemies. Leaders of states whose citizens participate in this war should understand that this could have the most negative consequences for them. The same goes for those who have now taken the side of "independent" Chechnya, who have taken a "pro-Chechen" position.

7. Chechnya is a threat to all Christian civilization.

The West did not protest against the shooting of the Russian parliament in October '93. The West protests now. The Christian West once again supports Muslim lawlessness. Like in Yugoslavia, where insolent from permissiveness and impunity, Bosnian Muslims burn out Christians on their own lands. The same is happening now in Chechnya, where brutalized Islamic fanatics under green banners kill, gut, rape, castrate Russian boys. Russian border guards on the Tajik-Afghan border have been declared "holy war" in retaliation for Chechnya: victims are counted in dozens.

The West, apparently, doesn't understand that the current change in the geopolitical situation in and around Russia is dangerous not only for Russia but for all Christian civilization. Where is the damned Pope looking, traveling around the world with endless tours? Does he not care about the fate of hundreds of dying Russian Christians? Or is the Vatican also already on the side of Muslims?

8. Take the "Chechen diaspora" hostage!

I was most struck by the cynicism and insolence of Chechens living in Moscow, the so-called "Chechen diaspora." Recently, our "pro-Chechen" TV has given them a lot of attention. Sometimes they make some kind of appeals, sometimes Chernomyrdin discusses with them the possibilities of peaceful settlement of the conflict! There's a war going on, uncle, a war with Chechens, a war against them, and you're asking them for advice! If they're on our side, they should address their people demanding immediate surrender of weapons and themselves; if they're against us – they shouldn't be invited to the Kremlin for meetings, not shown on TV, but taken hostage and exchanged for Russian prisoners (if only members of the "Chechen diaspora" are needed by their people at all). The same applies to representatives of the so-called "Chechen business," built on blood (of course!), on robbery and banditism, and until quite recently called the "Chechen mafia." Not a single Chechen on Russian territory should sleep peacefully until order is established there. And all "Chechen business" should be immediately nationalized.

9. The blood of Russian soldiers is the ineptitude of generals.

War is the finest hour of any soldier when the soldier knows he's a hero, when he knows whom and for what he's killing. When a soldier hears from all sides that he's a murderer and scum, when he knows he's carrying out the orders of assholes who've lost control not just of the country but of themselves, he's demoralized; from a war hero he turns into its victim.

Inept generals, cowardly staff rats, use soldiers as cannon fodder, sending conscripts to war, not professionals. The incompetent defense minister, who only has experience shooting at unarmed Russian demonstrators and at the Russian parliament itself, has disgraced the Russian army, the Russian soldier, and Russian weapons for the whole world to see. The siege of Grozny is lasting longer than the storming of Berlin! There have been several situations when completely disoriented Russian units fired at each other for hours... A landing force of 45 people was captured by locals immediately after landing... In two months of war – dozens, hundreds of examples of inept command of combat operations!

"And these are the Russians who have been scaring us all these years?!" mocks a CNN commentator.

Unprecedented corruption in the Russian army has led to Chechnya being stuffed with Russian weapons, plundered or sold "on the side." The entire current government leadership of Russia, not just the military, is involved in the sale of weapons to Chechnya. By Grachev's order, all documents related to these schemes are being removed. It seems that this time, too, no one will learn the truth, and no one will be punished for the fact that Russian boys in Chechnya are now being killed with Russian weapons.

Glory to the Russian soldier! Shame on the thieves in epaulets!

10. "Kowtowing to the West."

Comparing Russian and Western reports from Chechnya, one can unerringly determine where "the wind is blowing from." The West acts as a provocateur. CNN has reported since the first days of the war about many thousands of casualties among civilians and many hundreds of killed Russian soldiers. Of course, the figures are "approximate" and unconfirmed and unrefuted by anyone, but the effect is grandiose: "Russians are aggressors," "Russians are murderers," "Russians are occupiers," etc.

The professional widow Bonner, smoking "cigarettes for real men," speaks of the danger threatening the young Soviet democracy, asks for pressure to be applied. The principle of action is the same as that of her browbeaten hubby, who demanded from the West tightening of political and economic sanctions against the hated Fatherland...

Rosy-cheeked Gaidar, pursing his lips like a bow, pontificates about the threat of an authoritarian regime...

The eternally sleepy curly lamb Yavlinsky demands the immediate resignation of the president...

The fierce "pink communist" Zyuganov with a terrible face has so gotten into the role of a "pocket oppositionist" that he's already ready to fraternize with all his former sworn enemies...

No one disdains speculation on the Chechen theme; no one misses the opportunity to crawl onto the "blue screen" and earn extra political points on someone else's blood (although political points are never extra).

Under Stalin, "kowtowing to the West" warranted a prison term. Now all Russian politics is done only with a glance at the West.

11. A Nobel Prize for betrayal of the Motherland?

In such extreme situations as war, it becomes clear who's worth what. This applies primarily to politicians. Over the past two months, we've seen many political metamorphoses, much human meanness, and outright betrayals. And if there were some scale for these categories, the most significant position on it should be occupied by the "famous human rights activist" Sergei Adamovich Kovalev, who lately has been called nothing less than "the conscience of Russia, its pride."

The "torturer of frogs" (Limonov's discovery: it turns out that Kovalev in 1964 defended his candidate's dissertation on "Electrical properties of myocardial fibers of the frog's heart"!) spent more than ten years in Soviet camps. It's known that camp experience has never ennobled anyone (it seems only Solzhenitsyn thinks otherwise). It broke some, like Shalamov, who devoted all his considerable talent to the "camp theme"; for others, it became a test of spiritual and physical endurance (Sinyavsky and Daniel); for others, it opened a brilliant career in the West (the same Solzhenitsyn, Brodsky); and for others it embittered and made them enemies of their own Motherland, their own people, like Kovalev.

By his very appearance as a sniffling intellectual rat, this Sakharov's successor is capable of causing disgust in physically and mentally healthy people. And when he opens his mouth, Sakharov's intonations just burst out of him! With visible pleasure, he plays the role of Prophet, poses before numerous photo and TV cameras, affectedly squeezing out of himself words about the terrible atrocities of Russian occupiers. From all sides, he feels the warm breath of the West and the support of his "democratic" brothers. Where was this creeping "conscience and pride of Russia" in October '93? Was he re-reading Sakharov or Solzhenitsyn?

Kovalev has taken a treacherous, anti-Russian position, and if he receives the Nobel Peace Prize as a fee for his betrayal, following Sakharov and Gorbachev, this will be another proof of the West's hostility towards Russia. However, there's already more than enough of such evidence.

12. The war in Chechnya is on the conscience of the "democrats."

Having dismantled the Soviet Union, the "democrats" are joyfully ready to support any separatists, to reduce to a minimum the size of Russia, which they hate.

Dudayev was the darling of our "democrats," who closed their eyes even to the fact that Chechnya had turned into a world center of terrorism, arms trade (Russian), and drugs. The budget of this "state" was based on these three items (plus the export of Russian oil).

The "democrats" nursed and nurtured the Dudayev regime, pampered his gang. (It's enough to remember how much the frenzied democrat Novodvorskaya howled about the need to recognize Chechen independence. She still adores Dudayev; the poor woman is still seized by orgasmic convulsions at the mere mention of his name.) Armed to the teeth, Dudayev began to "get out" of the democratic harness, beginning to bite the hand that fed him so deliciously and generously.

Now the "little democrats" play peacemakers, although they did everything to ensure that Dudayev, insolent from impunity, provoked this conflict. Now they diligently pretend to be noble, "deliberately ignoring" Dudayev's treachery. Now they're looking for the right and the guilty in this war, although they themselves are guilty of it more than anyone else.

13. What are the "democrats" afraid of?

"Pro-democratic" media reported with sepulchral voices about the capture of the presidential palace in Grozny. The mournful intonations were evidence that the "democrats" fear the Chechen war, but even more they fear our victory. Not because of Russian blood. Far from it – how much of this blood they themselves have already drunk! They fear a national uprising among Russians. They fear that after the victory over the Chechens, Russians will finally pay attention to their non-Russian physiognomies.

Yeltsin has played the "Chechen card" too successfully to hope to continue managing him like a puppet. Chechnya has become the complete collapse of the "democratic" movement in Russia, and on its ruins...

Source: http://www.newlookmedia.ru/?p=15377 © Publishing House "New View"

It is interesting to juxtapose this article by gay activist, journalist, and professional épateur Yaroslav (“Slava”) Mogutin with a piece published a year earlier: “The View from the Other Side,” which appeared in Top Secret (Sovershenno sekretno), a monthly magazine in print since 1989. Mogutin’s 1994 piece responds to supercilious othering, abusive stereotyping, and paranoid fantasies toward a human category to which he himself belongs: gay men. Here, writing on the First Chechen War (1994-96), he indulges freely in dehumanizing Orientalism in relation to the Chechen people. The text presents a list of vicious and demeaning tropes about Chechens and reduces the nation as a whole to barbaric “headhunters” and “terrorists.” In a third article from the same period, “Homosexuality in Soviet Prisons and Camps” (1993), Mogutin had rancorously reproached a Soviet political dissident class hostile or indifferent to the system’s persecution of gay men for its inability to recognize the injustice of oppression based on sexual difference. In “The Chechen Knot,” he displays this same unwillingness to recognize the injustice of oppression based on ethnic and religious difference.

Besides trafficking in racist stereotypes, “The Chechen Knot” includes complaints about Russian society’s lack of patriotism and solidarity. Expressing the general anxiety radiating outward from Soviet collapse, Mogutin condemns the divisive factionalism of the Constitutional Crisis of 1993, which ended with President Boris Yeltsin bombing his own parliament. In the fragmented social and political reality that succeeded the seventy-year-old Soviet regime, itself the product of tsarist-era failures, Mogutin and many of his contemporaries turned to conservatism as a possible basis for social cohesion.

Some of Mogutin’s adversaries, including journalist Aelita Efimova, chose what Americans might recognize as traditional family-values conservatism, positing the nuclear family, with its sharply demarcated gender roles, as the basic constituent unit of society. Efimova and her ilk promoted the marginalization and containment, if not the active persecution, of alternative sexualities and gender expressions in the name of preserving society’s integrity. For Mogutin, the key societal binder was a sense of national identity that included a confessional (Christian) dimension. In this scheme, non-Christians and non-Russians would be relegated to the margins. The combination of LGBTQ activism and aggressive Russian nationalism was not unique to Mogutin: another prominent example of this tendency was Evgeniya Debryanskaya, a lesbian activist and wife to far-right “philosopher” Alexander Dugin.

Mogutin’s militant masculinity displays a great-Russian chauvinism that easily shades into other “isms,” including misogyny—exemplified in his assertion that female snipers must not be “getting any” from their men at home. Sociologist Laurie Essig believes that Russian legal authorities exploited the virulent ethnic prejudice in “The Chechen Knot” to prosecute their homophobic prejudice against Mogutin. He was charged with inciting racial hatred and, on the advice of his lawyers, sought asylum in the US, a country he had denounced in “The Chechen Knot” as an ignorant and arrogant critic of Russia’s military action in Chechnya.