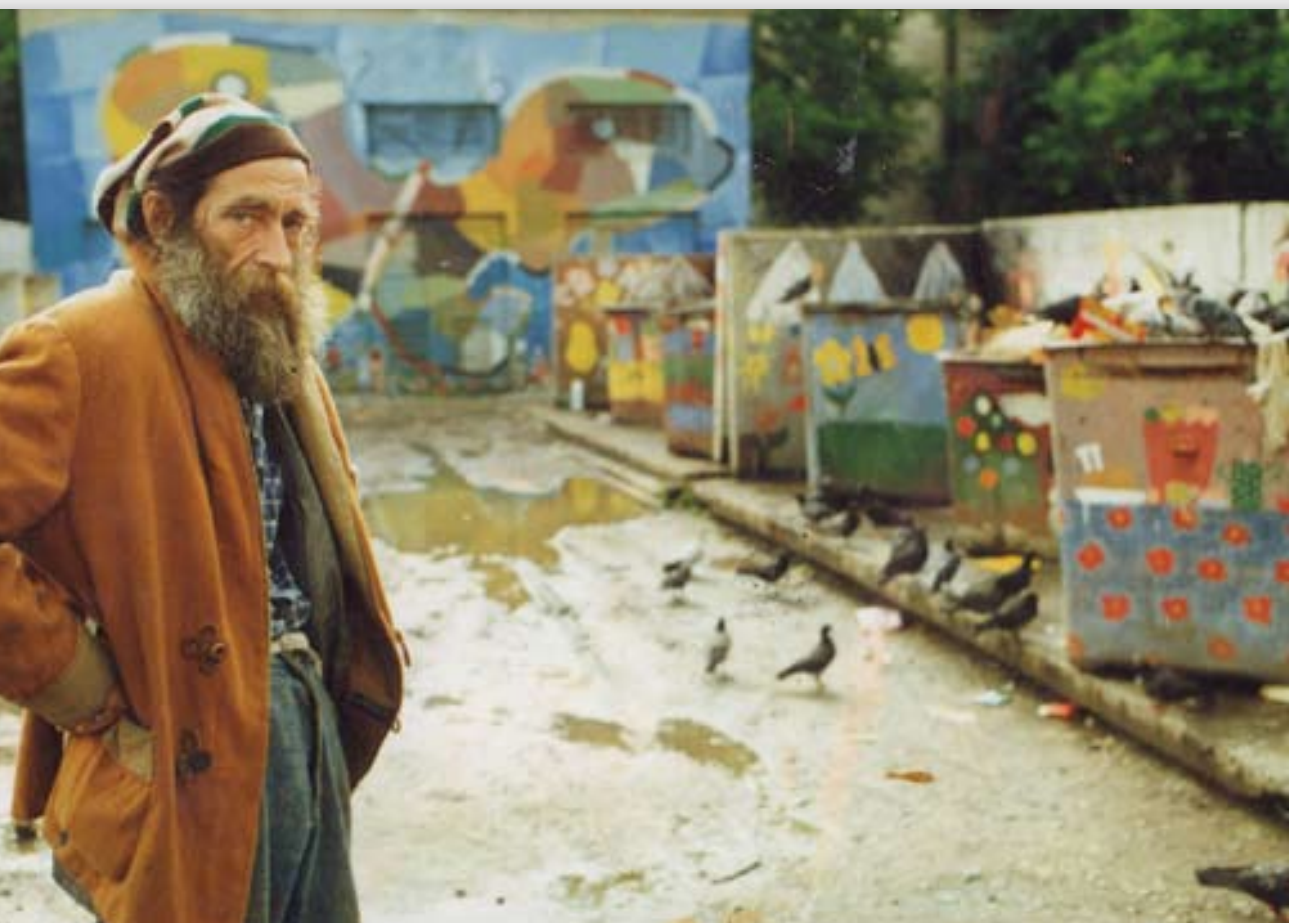

Filed Under: Performance > Political > B. U. Kashkin in front of painted rubbish bins at the Ural Electro-Technical Institute, 1993.

B. U. Kashkin in front of painted rubbish bins at the Ural Electro-Technical Institute, 1993.

B.U.Kashkin among painted trash containers from the Ural Electro-Technical Institute, 1992.

In 1992, artist B. U. Kashkin’s (1938-2005) collective initiated a series of actions called “The People’s Janitors of Russia [Narodnye dvorniki Rossii]” in which they first cleaned and decorated a public trash area; then painted the bins with murals; and, finally, held an impromptu art show and musical performance for passersby. The works use trash, and “trashed” spaces, as a basis for socially positive intervention that maintains the anarchic and engaging character of the collective’s prior public performances. The result of such actions is a beautified public space, as a site designated for ugliness and decay is instead transformed into a place of collective play and art appreciation.

These photographs document a 1992 performance titled “Let’s turn trash bins into flowers/and put those flowers round our heads,” which took place at the Ural Electro-Technical Institute. B. U. Kashkin and his group painted trash bins with flowers and staged a performance involving paintings made on found cardboard and other refuse. These were hung on the aforementioned trash bins, as well as on fences and nearby trees, alongside signs advertising an art exhibit open to the general public. The performance included the group making kebabs over a grill while B. U. Kashkin drank tea, and others live-painted and immediately displayed finished artworks to “visitors” who either came intentionally, drawn in by the posters, or were simply there to drop off their garbage.

The Institute held special significance for B. U. Kashkin, who had worked there as an electrical engineer until 1992, when he apparently demoted himself to janitor, a move that confused his contemporaries. It is also notable that the collective’s shift to trash in art comes almost immediately after the beginning of Russia’s capitalist experiment. In this context, B. U. Kashkin’s action becomes a critical response to capitalism by deploying artistic tactics that leave no marketable remainder. The works are site-specific, ephemeral, and seem to be on the margin of legality, since it is unclear if Kashkin had official clearance to paint these containers. At the same time, by beautifying an “ugly” public space, the action is socially conscious and even collectivist in spirit.

The trash bin works represent B. U. Kashkin’s commitment to an anarchist, punk-jester aesthetic and praxis combining antisocial or subversive tactics with prosocial messages and positive values. They also make apparent that the introduction of market capitalism caused B. U. Kashkin to shift strategies. Although he no longer distributed his paintings into public circulation quite as freely as before, he engaged site specificity to ensure their benefit remained available to as many people as possible.