Filed Under: Print > Kompromat, trolling, or memory wars > The pro-Yeltsin propaganda paper “God Forbid!” subjects Communist presidential candidate Gennady Zyuganov to blistering critique

The pro-Yeltsin propaganda paper “God Forbid!” subjects Communist presidential candidate Gennady Zyuganov to blistering critique

[2 items]

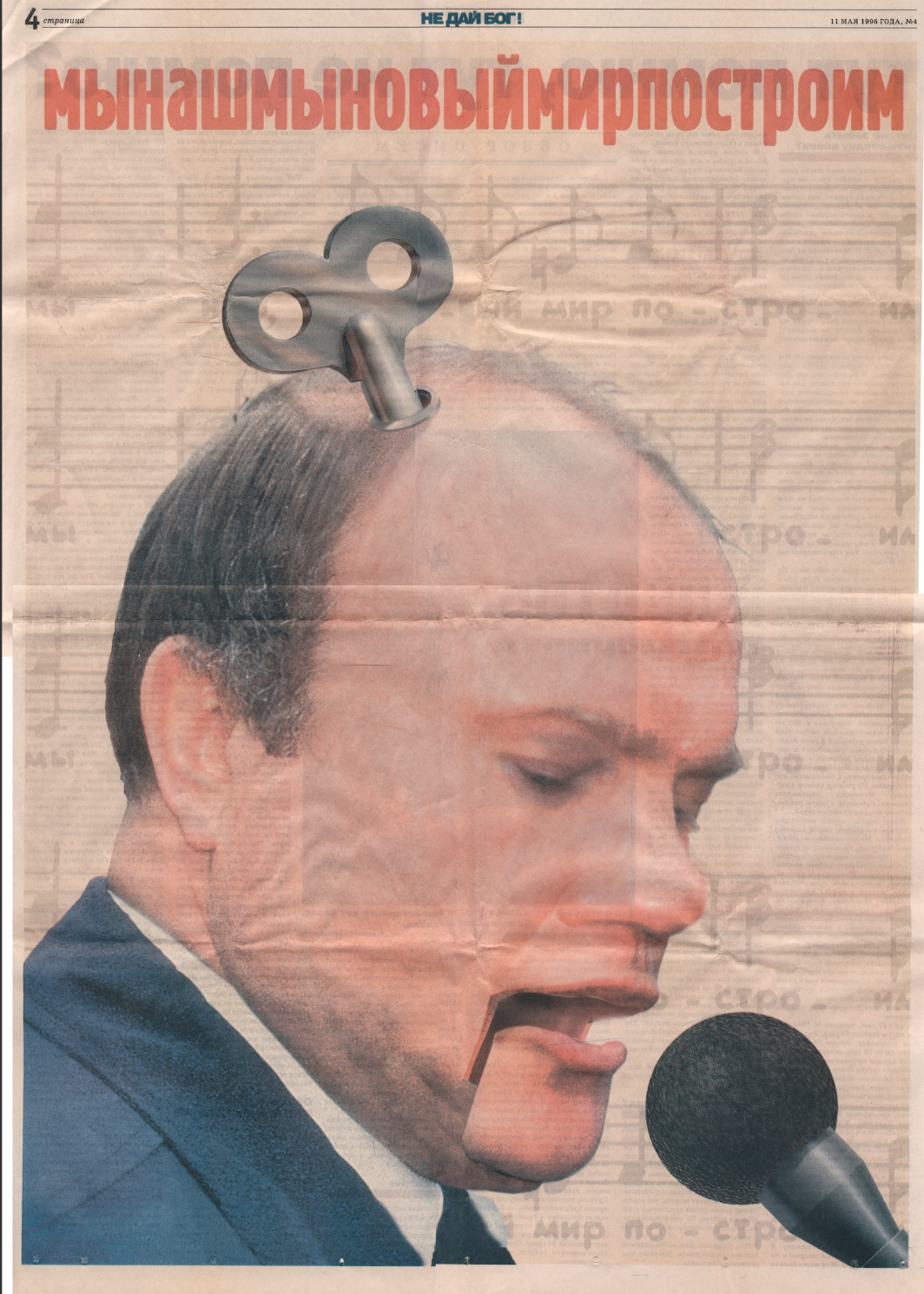

First image—Red text reads: "Theworldisabouttochangeitsfoundation [sic]"

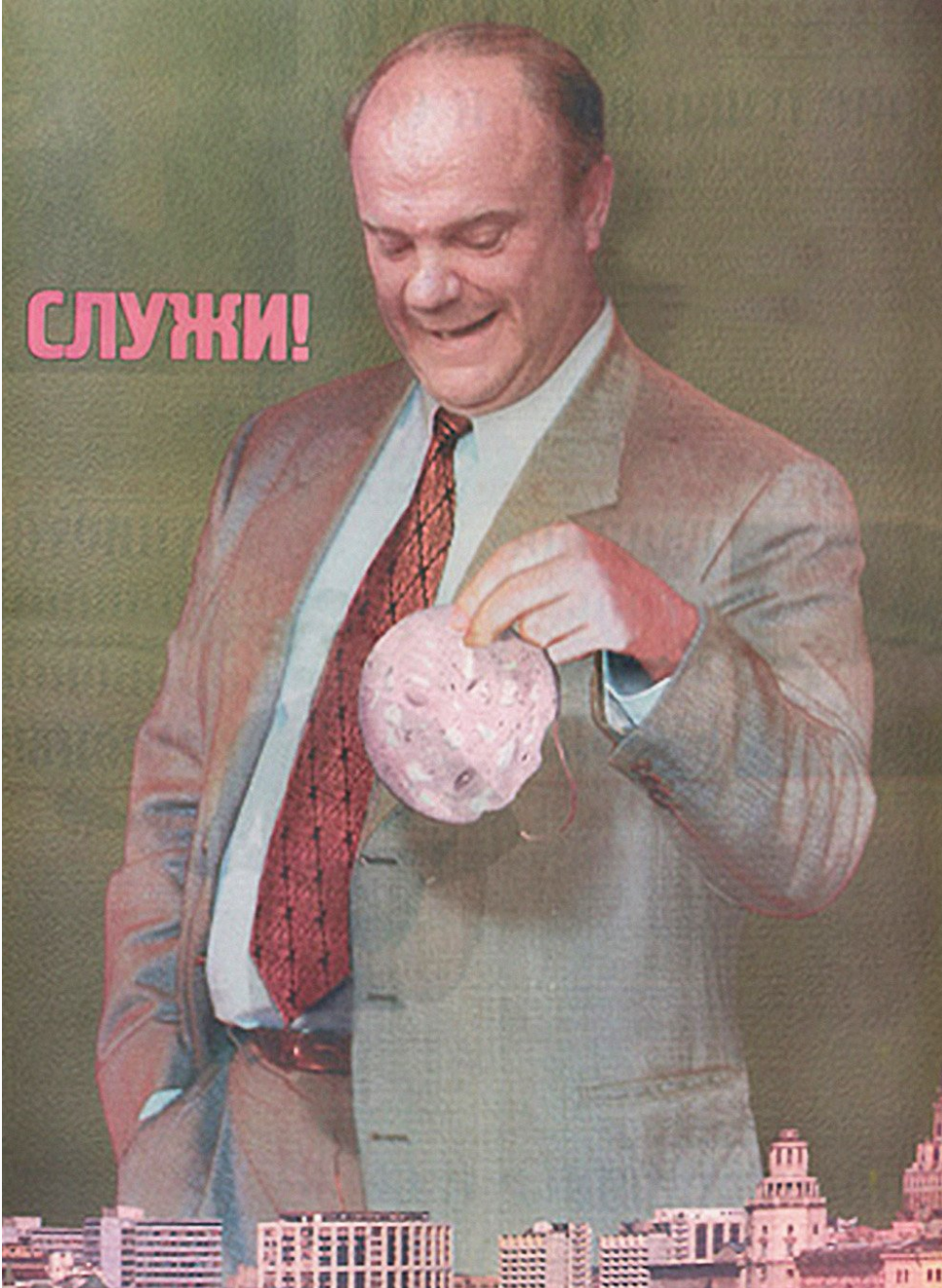

Second image—Red text reads: “Beg!”

With Yeltsin facing long odds for re-election in 1996, some of Russia’s richest men decided to put their collective thumb on the scale for the foundering candidate—who, whatever his flaws, would be better for their growing wealth than the Communist Gennady Zyuganov. Leveraging their power as newly minted media magnates, some of the members of the so-called Davos Pact—informally concluded at the Davos Economic Forum in March 1996—began flooding the Russian media environment with pro-Yeltsin propaganda.

Another effort in this vein was the short-lived “newspaper” God Forbid!, published under the aegis of the Wall Street Journal-like Kommersant daily, then owned by journalist Vladimir Yakovlev. The fearsome event to which the paper’s name referred was a possible Zyuganov victory—and in case the name God Forbid! wasn’t clear enough, the subtitle clarified that the paper was dedicated to imagining “what could happen in Russia after 16 June,” when first-round elections were scheduled to take place.

At a moment when Soviet state subsidies had ended and many outlets were struggling to stay afloat, God Forbid! exhibited uncharacteristically high production values. Subscriptions were free, its pages contained no ads, and it appeared in full color on relatively high-quality paper. These attributes were assured by God Forbid!’s $8 million budget, which journalists later traced to “shock therapy” architect Anatoly Chubais’s Private Property Fund. The paper’s tone was apocalyptic: it proclaimed that only the clinically insane would vote for Zyuganov; portrayed him as a creepy Internationale-mouthing automaton (above, from issue no. 4) or a salami-wielding dog owner (“Beg!”, above, from issue no. 6); and compared him to Adolf Hitler.

In print only from April to June 1996, God Forbid! disappeared once its 9 issues had helped win Yeltsin a second term. Its brief reappearance during the presidential elections of 2012, when it criticized the Bolotnaya Square protests, served only to underscore its function as a propaganda organ shilling for incumbent statesmen—a far cry from early-1990s dreams of a truly independent Russian media.