Filed Under: Print > Journalism > The Rise of Public Opinion Polling

The Rise of Public Opinion Polling

[3 items]

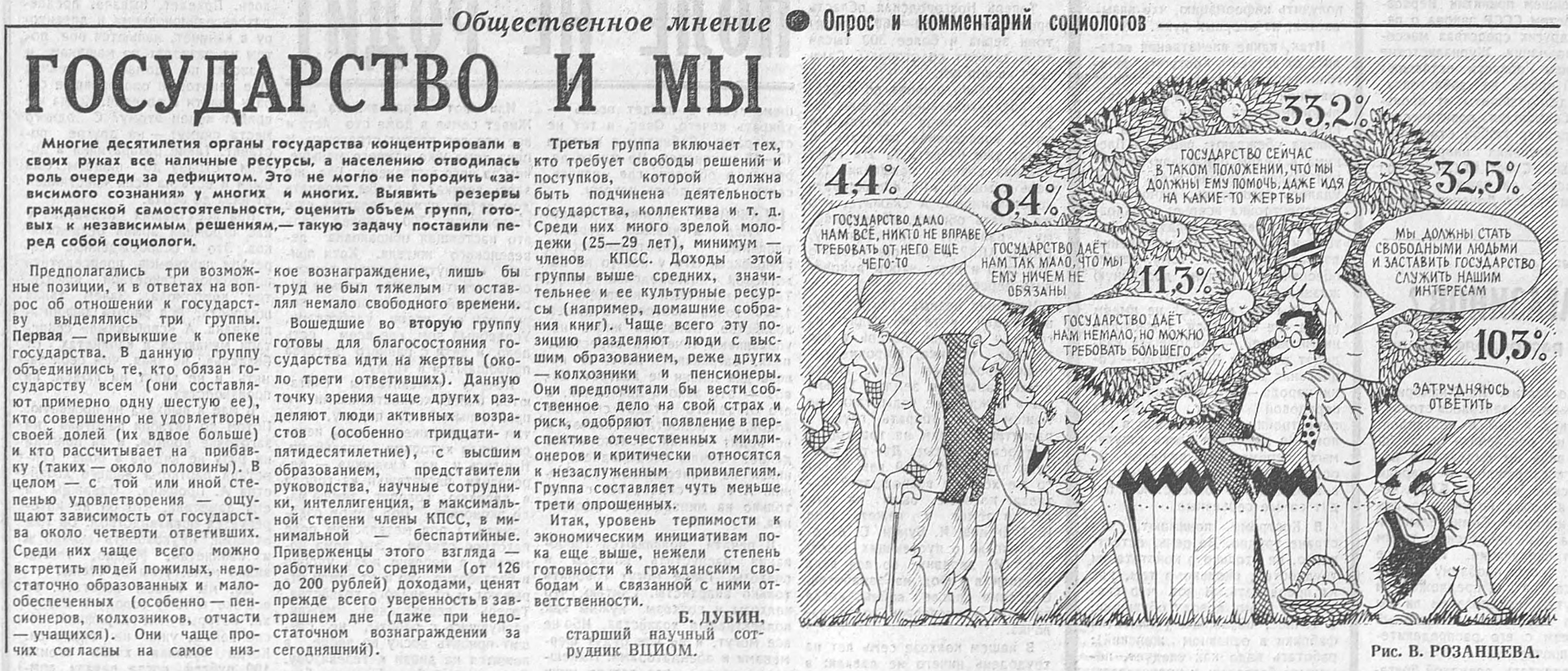

The All-Union (after 1992, All-Russian) Center for the Study of Public Opinion (Vsesoiuznyi / Vserossiiskii tsentr izucheniia obshchestvennogo mneniia or VTsIOM) was founded in 1987 as part of glasnost-era efforts to encourage openness and help the government better understand the populace. After the fall of the Soviet Union, VTsIOM became the Russian Federation’s most important polling organization, providing reliable statistics on a wide range of topics, from presidential approval ratings and consumption habits to reading preferences. It worked with regional and international organizations to develop a broad data-gathering network across the post-Soviet space in an ambitious attempt to understand the economic and social changes the country was undergoing.

The founders of VTsIOM, including Tatiana Zaslavskaia, Yuri Levada, Lev Gudkov, and Boris Dubin, saw their work as an attempt to approach objective truth through broad-based statistical analysis. For them, raw data was the distilled essence of the promise of glasnost. Accordingly, over half of each issue of Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniia, VTsIOM’s main publication, is devoted to reams of raw statistical data—a gesture of perhaps futile, but radical openness. Educated in the Soviet Union, the project’s sociologists were suspicious of uncomplicated positivism and committed to core principles of Marxian analysis. These intellectual commitments persisted even through their deep reading of Western sociology and cultural theory.

The first half of Monitoring, filled with analytical essays and interpretations alongside exhaustive methodological notes, makes these allegiances plain. One essay, for instance, discusses a new poll showing an increasing number of Russian citizens identifying with the value of individual success propagated by the new capitalist economy. Instead of leaving it there, however, the essay shows how the commercial mass media propagates a simple narrative of “capitalist utopia” in which positive actions are reliably rewarded. The raw numbers are offered, but context and critique are also close at hand. Besides featuring statistics with the power to sway presidential campaigns and price regulations, each issue of the periodical thus also staged an essential conflict at the heart of post-socialist culture. On one side was a profound faith in statistics as an objective measure of an existing social truth; on the other, a suspicion of the positivism represented by those statistics, fed by years of Soviet education and by the jarring nature of post-Soviet experience.

VTsIOM’s sociologists occupied both sides of this conflict, exhibiting both faith in, and skepticism toward, statistical research. In the pages of their periodical, they worked through the conflict and produced the sociology that would be most characteristic of post-socialist culture. That sociology turned to broad-based, statistically represented public opinion as the best way to know the post-Soviet people. In doing so, it overshadowed (and often replaced in the press) qualitative feedback mechanisms, such as letters to editors and citizen-correspondents. At the same time, it brought in Western theories from sources as varied as Gallup in the U.S. to German reader-response theory in order to understand public opinion in a new way.

The founders of VTsIOM, including Tatiana Zaslavskaia, Yuri Levada, Lev Gudkov, and Boris Dubin, saw their work as an attempt to approach objective truth through broad-based statistical analysis. For them, raw data was the distilled essence of the promise of glasnost. Accordingly, over half of each issue of Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniia, VTsIOM’s main publication, is devoted to reams of raw statistical data—a gesture of perhaps futile, but radical openness. Educated in the Soviet Union, the project’s sociologists were suspicious of uncomplicated positivism and committed to core principles of Marxian analysis. These intellectual commitments persisted even through their deep reading of Western sociology and cultural theory.

The first half of Monitoring, filled with analytical essays and interpretations alongside exhaustive methodological notes, makes these allegiances plain. One essay, for instance, discusses a new poll showing an increasing number of Russian citizens identifying with the value of individual success propagated by the new capitalist economy. Instead of leaving it there, however, the essay shows how the commercial mass media propagates a simple narrative of “capitalist utopia” in which positive actions are reliably rewarded. The raw numbers are offered, but context and critique are also close at hand. Besides featuring statistics with the power to sway presidential campaigns and price regulations, each issue of the periodical thus also staged an essential conflict at the heart of post-socialist culture. On one side was a profound faith in statistics as an objective measure of an existing social truth; on the other, a suspicion of the positivism represented by those statistics, fed by years of Soviet education and by the jarring nature of post-Soviet experience.

VTsIOM’s sociologists occupied both sides of this conflict, exhibiting both faith in, and skepticism toward, statistical research. In the pages of their periodical, they worked through the conflict and produced the sociology that would be most characteristic of post-socialist culture. That sociology turned to broad-based, statistically represented public opinion as the best way to know the post-Soviet people. In doing so, it overshadowed (and often replaced in the press) qualitative feedback mechanisms, such as letters to editors and citizen-correspondents. At the same time, it brought in Western theories from sources as varied as Gallup in the U.S. to German reader-response theory in order to understand public opinion in a new way.