Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Top Secret: Investigative Journalism and True Crime During Perestroika

Top Secret: Investigative Journalism and True Crime During Perestroika

[2 items]

This first issue of the monthly magazine Sovershenno sekretno (Top Secret), the first fully independent, privately owned periodical in Soviet Russia since 1917, captures the emergent journalistic style and media discourse of the mid- to late 1980s. This style combined investigative journalism—underpinned by a yearning for transparency and truth—with sensationalism and a fascination with sex and violence. Sovershenno sekretno was the brainchild of best-selling author Yulian Semyonov (1931-1993), widely known in Russia as the creator of Stierlitz, the Soviet undercover spy working in Nazi Germany from the blockbuster Soviet TV series Seventeen Moments of Spring (1973). Semyonov also founded and directed the International Association of Crime and Political Fiction (Russian acronym: MADP), which sold Sovershenno sekretno four to six times a year alongside an almanac called Detektiv i politika (Crime Fiction and Politics).

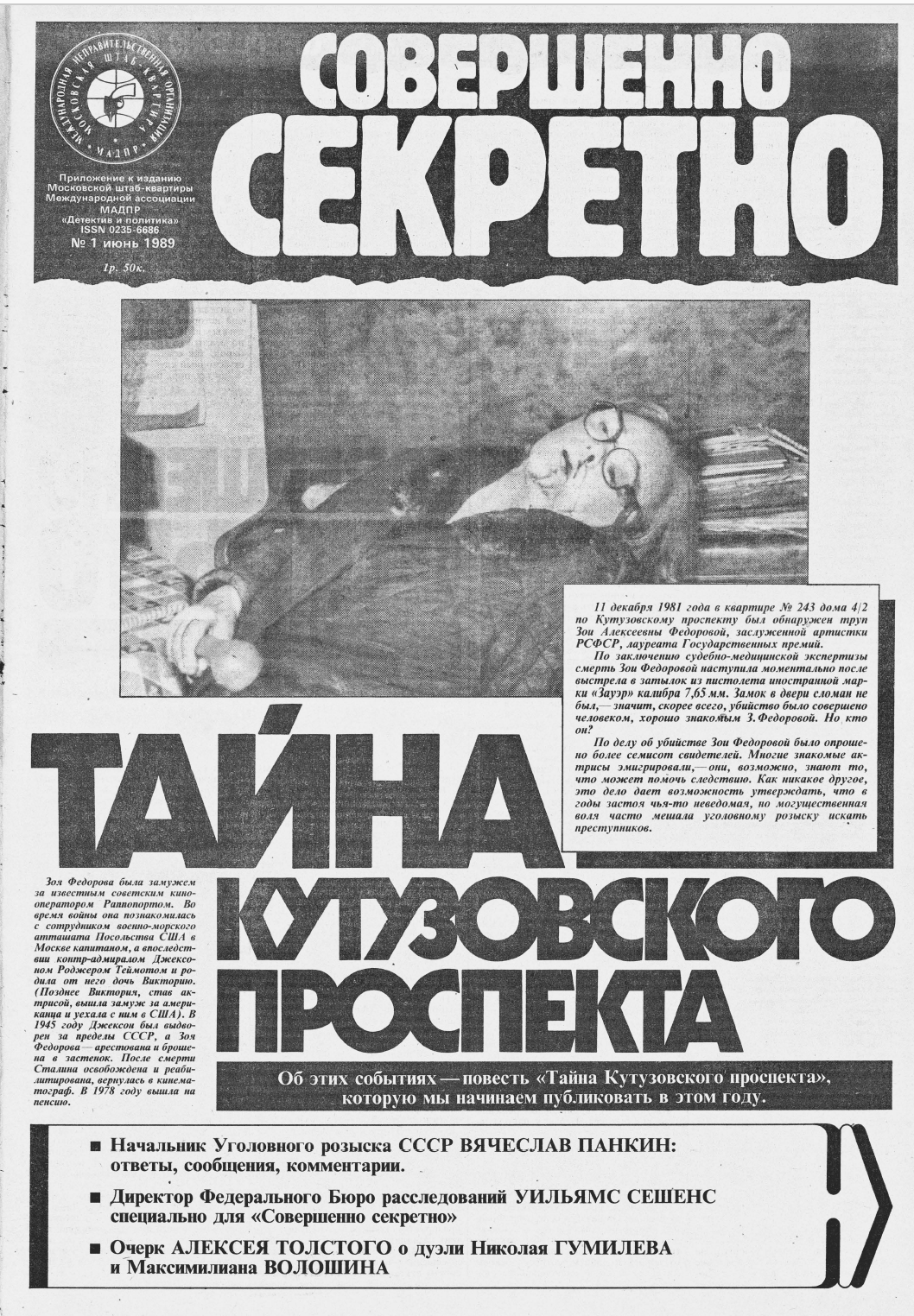

Sovershenno sekretno wasted no time in capitalizing on the shock value of violent images. The cover of its first issue, from June 1989, featured the lifeless body of Soviet actress Zoya Fyodorova (1907-1981). Found dead in her Moscow apartment on 11 December 1981, she had been killed by a single gunshot to the back of the neck, fired from a German-made Sauer pistol. The corresponding article provided a brief account of the unsolved case, but the heading promised a novella focusing on these events, The Mystery of Kutuzov Prospekt, which the magazine was planning to publish in several installments. In contrast with the grabby, entertaining, macabre headline, Semyonov’s editorial on the facing page switched, in both tone and content, to a much more poised and even-handed analysis of current events. The piece, “Fully Public” (a play on the magazine’s name, whose literal Russian meaning is “Fully Secret”), presented a curious mix of Reaganism and Leninism—in Semyonov’s idiosyncratic interpretation of each— and the “the fight against bureaucratism” that was a rallying cry of perestroika.

Sovershenno sekretno’s early issues are striking for this combination of serious reporting and in-depth political analysis with salacious stories and true-crime narratives. The magazine alternated articles about serial killers and unsolved murders with scholarly essays by prominent Russian economists and political scientists; literary and philosophical sections with previously unpublished pieces on—and by— authors like Nikolay Berdiaev and Yevgeny Zamyatin; and political commentaries about Soviet dissidents, Solidarność (Solidarity) in Poland, and the national movements throughout the Soviet bloc. Both the magazine and its literary supplement—Detektiv i politika—used the genres of crime and spy fiction, political fantasy, and sci-fi as underlying threads connecting popular entertainment with investigative journalism, reflecting larger cultural trends during perestroika. In part due to a lack of affordable alternatives, crime novels or detektivy were important forms of popular entertainment in the 1980s and 1990s. At the same time, during perestroika, violence and chernukha (gore) became implicitly associated with sincerity and truth—and with the moral mission to reveal and amend society’s darkest evils. Consequently, the era’s acute yearning for truth, transparency, and information characterizing media discourses coincided with a love of transgression and the extreme. The appearance of these new themes coincided with the emergence of a personalized, original journalistic language—often veering into irony and provocation—that diverged sharply from the flat and hypernormalized (Yurchak) language of the Soviet press.

Sovershenno sekretno wasted no time in capitalizing on the shock value of violent images. The cover of its first issue, from June 1989, featured the lifeless body of Soviet actress Zoya Fyodorova (1907-1981). Found dead in her Moscow apartment on 11 December 1981, she had been killed by a single gunshot to the back of the neck, fired from a German-made Sauer pistol. The corresponding article provided a brief account of the unsolved case, but the heading promised a novella focusing on these events, The Mystery of Kutuzov Prospekt, which the magazine was planning to publish in several installments. In contrast with the grabby, entertaining, macabre headline, Semyonov’s editorial on the facing page switched, in both tone and content, to a much more poised and even-handed analysis of current events. The piece, “Fully Public” (a play on the magazine’s name, whose literal Russian meaning is “Fully Secret”), presented a curious mix of Reaganism and Leninism—in Semyonov’s idiosyncratic interpretation of each— and the “the fight against bureaucratism” that was a rallying cry of perestroika.

Sovershenno sekretno’s early issues are striking for this combination of serious reporting and in-depth political analysis with salacious stories and true-crime narratives. The magazine alternated articles about serial killers and unsolved murders with scholarly essays by prominent Russian economists and political scientists; literary and philosophical sections with previously unpublished pieces on—and by— authors like Nikolay Berdiaev and Yevgeny Zamyatin; and political commentaries about Soviet dissidents, Solidarność (Solidarity) in Poland, and the national movements throughout the Soviet bloc. Both the magazine and its literary supplement—Detektiv i politika—used the genres of crime and spy fiction, political fantasy, and sci-fi as underlying threads connecting popular entertainment with investigative journalism, reflecting larger cultural trends during perestroika. In part due to a lack of affordable alternatives, crime novels or detektivy were important forms of popular entertainment in the 1980s and 1990s. At the same time, during perestroika, violence and chernukha (gore) became implicitly associated with sincerity and truth—and with the moral mission to reveal and amend society’s darkest evils. Consequently, the era’s acute yearning for truth, transparency, and information characterizing media discourses coincided with a love of transgression and the extreme. The appearance of these new themes coincided with the emergence of a personalized, original journalistic language—often veering into irony and provocation—that diverged sharply from the flat and hypernormalized (Yurchak) language of the Soviet press.