Filed Under: Print > Literature > "Gone with the Wind"—The post-Soviet Sequels

"Gone with the Wind"—The post-Soviet Sequels

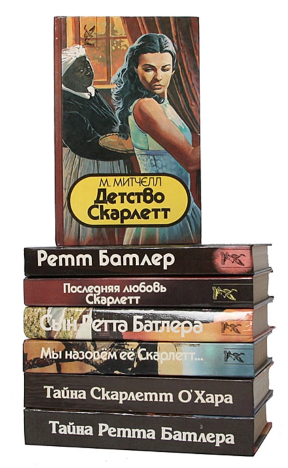

Inspired by the late-Soviet success of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936) and the more recent success of Alexandra Ripley’s Scarlett (1991; Russian translation 1992), the Minsk publisher Liesma sistems launched a series of unauthorized continuations of the Scarlett O’Hara story, written by anonymous author collectives and released under the apparently American pseudonym Dzhuliia Khilpatrik (“Julia Hillpatrick”).

The seven novels, several of which became bestsellers in Russia, represent an attempt to create a homegrown equivalent to the massively popular genre bestsellers then flooding the Russian book market. The earliest bestseller lists published in Russia made clear that, by the early 1990s, readers’ preferences had shifted away from the previously banned literature that had dominated perestroika-era publishing. In its stead came imported genre fiction by American authors like Stephen King, Danielle Steele, and James Hadley Chase. Soon, however, writers and publishers from the former Soviet Union began to deconstruct the bestseller in order to adapt it to local tastes.

Several of the most successful Russian authors of the 1990s successfully blended the bestseller conventions with local realia, creating new hybrid genres like the “woman’s detective novel” (zhenskii detektiv) of Aleksandra Marinina and Daria Dontsova—a mystery novel whose author, protagonist, and intended reader were all women—and the post-Soviet boevik or action thriller by the likes of Viktor Dotsenko, which grafted the conventions of bestsellers like Rambo (novel 1971, film version 1982) onto the crime-ridden chaos of post-Soviet Russia.

Another kind of imitative bestseller blossomed at the same time as these straightforward translations and adaptations. Collectively authored and pseudonymously published, these works were presented to the Russian reader as authentic imports. In a 1999 article called “How We Wrote a Bestseller,” the author Lev Lobarev describes being invited to participate in such a collective. The popular telenovela Simplemente Maria (Prosto Maria, 1989) had just finished its run on Russian television, and Lobarev’s group was tasked with writing a sequel called Forgive Me, Maria! (Prosti, Maria!), to be published as a “translation” from the Spanish by an “author” named Amanta Santos.

The Julia Hillpatrick books operate on a similar logic, appropriating the success of an already-popular cultural project through imitation and putative continuation. These collectively authored bestsellers honed the marketing strategies and literary aesthetics that would influence the Russian literary mainstream of the late 1990s and early 2000s, inspiring influential projects like the Erast Fandorin novels (1998-) by the pseudonymous Boris Akunin (1956-).

The seven novels, several of which became bestsellers in Russia, represent an attempt to create a homegrown equivalent to the massively popular genre bestsellers then flooding the Russian book market. The earliest bestseller lists published in Russia made clear that, by the early 1990s, readers’ preferences had shifted away from the previously banned literature that had dominated perestroika-era publishing. In its stead came imported genre fiction by American authors like Stephen King, Danielle Steele, and James Hadley Chase. Soon, however, writers and publishers from the former Soviet Union began to deconstruct the bestseller in order to adapt it to local tastes.

Several of the most successful Russian authors of the 1990s successfully blended the bestseller conventions with local realia, creating new hybrid genres like the “woman’s detective novel” (zhenskii detektiv) of Aleksandra Marinina and Daria Dontsova—a mystery novel whose author, protagonist, and intended reader were all women—and the post-Soviet boevik or action thriller by the likes of Viktor Dotsenko, which grafted the conventions of bestsellers like Rambo (novel 1971, film version 1982) onto the crime-ridden chaos of post-Soviet Russia.

Another kind of imitative bestseller blossomed at the same time as these straightforward translations and adaptations. Collectively authored and pseudonymously published, these works were presented to the Russian reader as authentic imports. In a 1999 article called “How We Wrote a Bestseller,” the author Lev Lobarev describes being invited to participate in such a collective. The popular telenovela Simplemente Maria (Prosto Maria, 1989) had just finished its run on Russian television, and Lobarev’s group was tasked with writing a sequel called Forgive Me, Maria! (Prosti, Maria!), to be published as a “translation” from the Spanish by an “author” named Amanta Santos.

The Julia Hillpatrick books operate on a similar logic, appropriating the success of an already-popular cultural project through imitation and putative continuation. These collectively authored bestsellers honed the marketing strategies and literary aesthetics that would influence the Russian literary mainstream of the late 1990s and early 2000s, inspiring influential projects like the Erast Fandorin novels (1998-) by the pseudonymous Boris Akunin (1956-).