Filed Under: Print > Literature > Bestsellers of Moscow

Bestsellers of Moscow

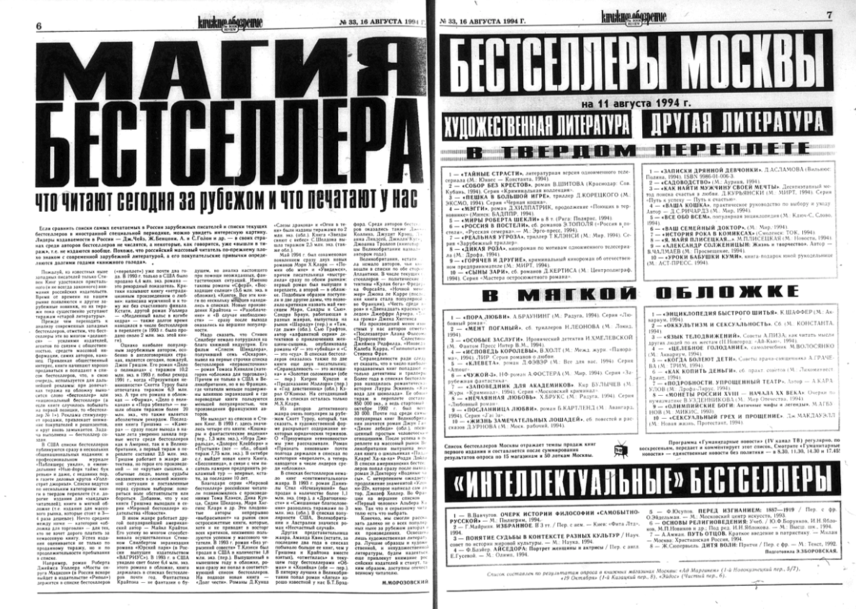

“Bestsellery Moskvy,” Knizhnoe obozrenie, no. 33 (16 Aug 1994): 6–7.

The 1990s bestseller lists published in The Book Review (Knizhnoe obozrenie), the trade periodical of Soviet and post-Soviet publishing, represent perhaps the most sustained testament to a nearly boundless faith that markets would be able to successfully regulate not only commerce, but culture as well.

The list presented here includes not only fiction and non-fiction titles, but also a category called “‘Intellectual’ Bestsellers.” The very presence of this category indicates critics’ unease with the idea of a book world reduced to little more than commercially successful products, pointing to a tension between market and intellectual values.

The term “bestseller” first appeared in The Book Review in January 1991, even before the fall of the Soviet Union, as a foreign term characteristic of mature cultural markets where supply and demand were in sync. By contrast, wrote Book Review editor Grigori Nezhurin, “Defining the bestseller in our country is a difficult task, almost hopeless,” because “too often one thing is desired for reading, another is read, a third is published, and as for what people buy, well…”

In the ensuing years, The Book Review built an apparatus for measuring reader demand that surveyed fifteen bookstores and 150 newsstands in Moscow and represented the top ten bestsellers in categories familiar to the Western consumer (but never particularly salient in Soviet-era publishing): hard- and soft-cover, fiction, and non-fiction. The bestseller lists first appeared in The Book Review on 26 November 1993, as a small notice in the bottom corner of page 2, but quickly blossomed into a full-page feature in the center of every issue.

Soon, the lists were joined by features attempting to understand or demystify the bestseller’s success with titles like “Anatomy of a Bestseller,” “The Life of a Bestseller,” or, in this artifact, “The Magic of the Bestseller.” In 1995, the facing page was given over to a weekly feature called “Formula for Success” that promised to teach Russian publishers how to reproduce the bestseller’s market effect.

These bestseller lists and the apparatus around them clearly aspire to a new, marketized culture critics and editors hoped the 1990s would bring: the enthusiastic adoption of market terminology; a statistical approach to measuring and representing the market’s apparently objective workings; and, finally, the conviction that anyone clever enough to decode the “formula for success” could manipulate the book market. The bestseller lists thus represent not only faith in markets, but also a growing polemic around market power.

The list presented here includes not only fiction and non-fiction titles, but also a category called “‘Intellectual’ Bestsellers.” The very presence of this category indicates critics’ unease with the idea of a book world reduced to little more than commercially successful products, pointing to a tension between market and intellectual values.

The term “bestseller” first appeared in The Book Review in January 1991, even before the fall of the Soviet Union, as a foreign term characteristic of mature cultural markets where supply and demand were in sync. By contrast, wrote Book Review editor Grigori Nezhurin, “Defining the bestseller in our country is a difficult task, almost hopeless,” because “too often one thing is desired for reading, another is read, a third is published, and as for what people buy, well…”

In the ensuing years, The Book Review built an apparatus for measuring reader demand that surveyed fifteen bookstores and 150 newsstands in Moscow and represented the top ten bestsellers in categories familiar to the Western consumer (but never particularly salient in Soviet-era publishing): hard- and soft-cover, fiction, and non-fiction. The bestseller lists first appeared in The Book Review on 26 November 1993, as a small notice in the bottom corner of page 2, but quickly blossomed into a full-page feature in the center of every issue.

Soon, the lists were joined by features attempting to understand or demystify the bestseller’s success with titles like “Anatomy of a Bestseller,” “The Life of a Bestseller,” or, in this artifact, “The Magic of the Bestseller.” In 1995, the facing page was given over to a weekly feature called “Formula for Success” that promised to teach Russian publishers how to reproduce the bestseller’s market effect.

These bestseller lists and the apparatus around them clearly aspire to a new, marketized culture critics and editors hoped the 1990s would bring: the enthusiastic adoption of market terminology; a statistical approach to measuring and representing the market’s apparently objective workings; and, finally, the conviction that anyone clever enough to decode the “formula for success” could manipulate the book market. The bestseller lists thus represent not only faith in markets, but also a growing polemic around market power.