Interview with Victor Pelevin

Victor Pelevin’s epoch-defining novel Generation P appeared in 1999. It portrayed a failed poet turned ad-man, Vavilen Tatarsky, who skewers post-Soviet society as he rises through its ranks. The novel became a touchstone for critiques of 1990s-era bandit capitalism. But the novel not only critiqued the manipulations of market capitalism—it participated in them.

Ever the canny entrepreneur, Pelevin leaked chapters from the novel before its release, then acted outraged when the texts spread online. The trick worked and the book—whose cover was splashed with Coca-Cola, Nike, and Pepsi logos—became a huge bestseller. In interviews around Generation P’s release, Pelevin seemed to perform a version of himself at least in part informed by his protagonist, Tatarsky—half 90s gangster, half cynical ad-man.

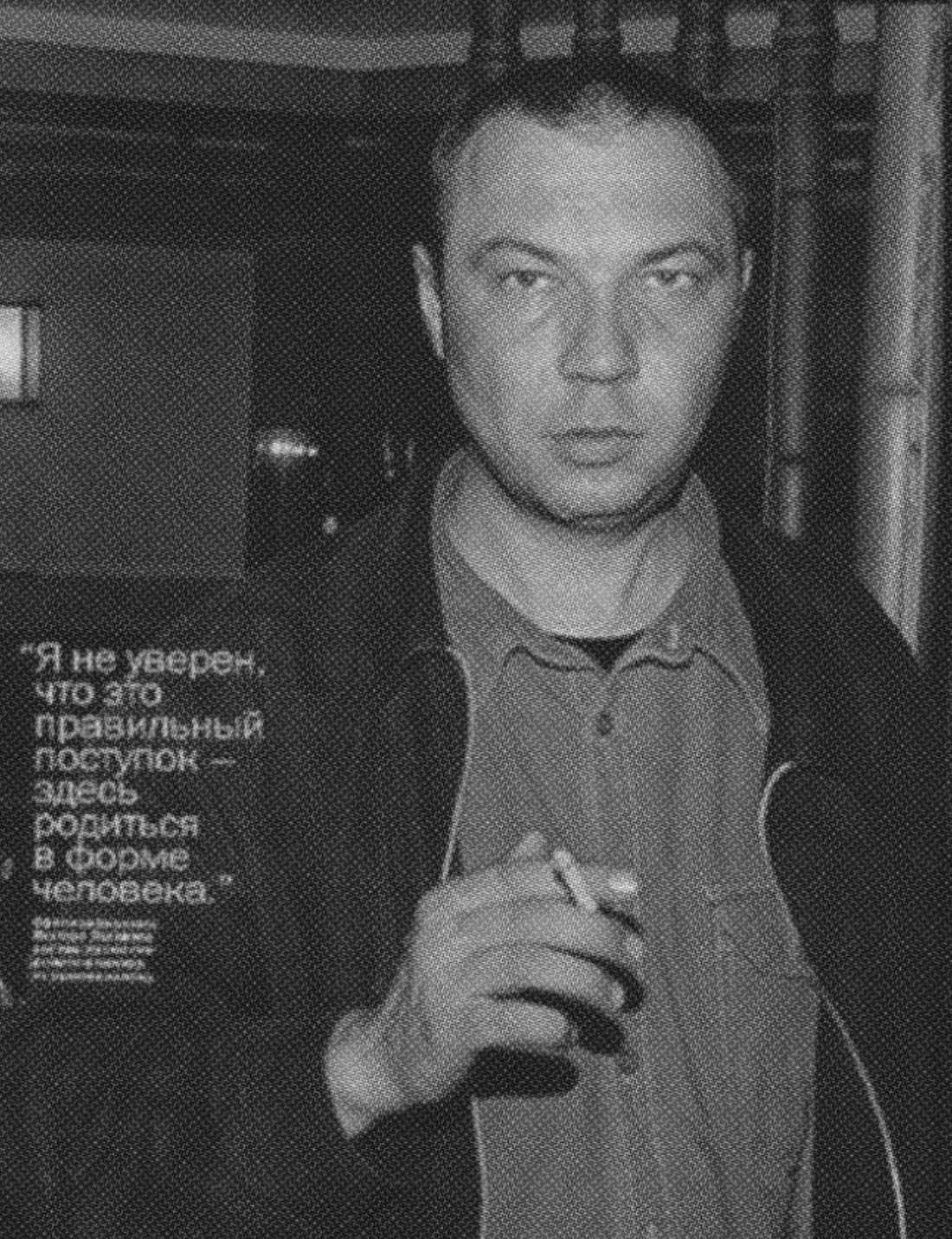

Asked about his favorite western philosophers for an interview with BOMB magazine, he cited “Rémy Martin” and “Jack Daniels,” then went on to say: “As far as I understand, thoughts are justified in two cases: when they quickly make us rich, and when they charm us with their beauty.” He often showed up late for interviews, discussed drinking or drugs, and spoke in the argot of the 1990s criminal underworld. Karina Dobrotvorskaia’s profile of the author for Vogue, for instance, began with Pelevin showing up an hour and a half late, clearly inebriated. Their conversation started pleasantly enough, but when Dobrotvorskaia turned on her recorder, Pelevin “exploded”: “Why you gotta harsh my mellow, huh? [Chto vy mne kaif lomaete, a?] This is the shame and horror of life! I was all ready to believe that a beautiful, smart girl would like me for me, that’s she’d want to just sit around and shoot the shit [pobazarit’].”

Pelevin lamented the venal (capitalist) motivations undermining any attempt at authentic communication. But he also refused to answer questions directly, laced responses with sexist come-ons, and deflated the conversation with 1990s slang borrowed from emerging gangster culture. The mixture of “gangster speech” and “abstract concepts” that Dobrotvorskaia observed in her subject certainly resonated with the novel Pelevin was promoting, but also pointed to something more substantial: a “strange and very energetic combination” of registers serving a specific purpose. Pelevin, the journalist noted, once said that “gangster lexicon” (leksika bratkov) has enormous power, and that the Russian language, “having fallen ill within [the confines of] intellectual discourse, was resurrected in the criminal milieu, revitalized through [contact with] the primordial concepts of life and death.”

The Vogue interview—like Pelevin’s fictional work—staged a collision of discourses and suggested the regenerative potential of such a collision. Although both Generation P and Pelevin’s performance around it were positioned, and read, as satire, they contributed to the language and practice of post-Soviet capitalism at the start of the new millennium.

Ever the canny entrepreneur, Pelevin leaked chapters from the novel before its release, then acted outraged when the texts spread online. The trick worked and the book—whose cover was splashed with Coca-Cola, Nike, and Pepsi logos—became a huge bestseller. In interviews around Generation P’s release, Pelevin seemed to perform a version of himself at least in part informed by his protagonist, Tatarsky—half 90s gangster, half cynical ad-man.

Asked about his favorite western philosophers for an interview with BOMB magazine, he cited “Rémy Martin” and “Jack Daniels,” then went on to say: “As far as I understand, thoughts are justified in two cases: when they quickly make us rich, and when they charm us with their beauty.” He often showed up late for interviews, discussed drinking or drugs, and spoke in the argot of the 1990s criminal underworld. Karina Dobrotvorskaia’s profile of the author for Vogue, for instance, began with Pelevin showing up an hour and a half late, clearly inebriated. Their conversation started pleasantly enough, but when Dobrotvorskaia turned on her recorder, Pelevin “exploded”: “Why you gotta harsh my mellow, huh? [Chto vy mne kaif lomaete, a?] This is the shame and horror of life! I was all ready to believe that a beautiful, smart girl would like me for me, that’s she’d want to just sit around and shoot the shit [pobazarit’].”

Pelevin lamented the venal (capitalist) motivations undermining any attempt at authentic communication. But he also refused to answer questions directly, laced responses with sexist come-ons, and deflated the conversation with 1990s slang borrowed from emerging gangster culture. The mixture of “gangster speech” and “abstract concepts” that Dobrotvorskaia observed in her subject certainly resonated with the novel Pelevin was promoting, but also pointed to something more substantial: a “strange and very energetic combination” of registers serving a specific purpose. Pelevin, the journalist noted, once said that “gangster lexicon” (leksika bratkov) has enormous power, and that the Russian language, “having fallen ill within [the confines of] intellectual discourse, was resurrected in the criminal milieu, revitalized through [contact with] the primordial concepts of life and death.”

The Vogue interview—like Pelevin’s fictional work—staged a collision of discourses and suggested the regenerative potential of such a collision. Although both Generation P and Pelevin’s performance around it were positioned, and read, as satire, they contributed to the language and practice of post-Soviet capitalism at the start of the new millennium.