Filed Under: Topic > Kommersant > Kommersant Board Game

Kommersant Board Game

[6 items]

Kommersant was part of a wave of board games released in the early 1990s as a response to the transition to market capitalism. Each aspired to a comprehensive epistemology of the new economic system that players could apply to their daily lives. Kommersant’s rules are no exception, opening with a mini-manifesto: “Our time—is a time of transition to new market relations. In particular, among the younger generation, there is a growing interest in the economy, and especially the latest developments. This game—is our effort to show, in general terms, key moments [sic] of the market, its laws and foundations.”

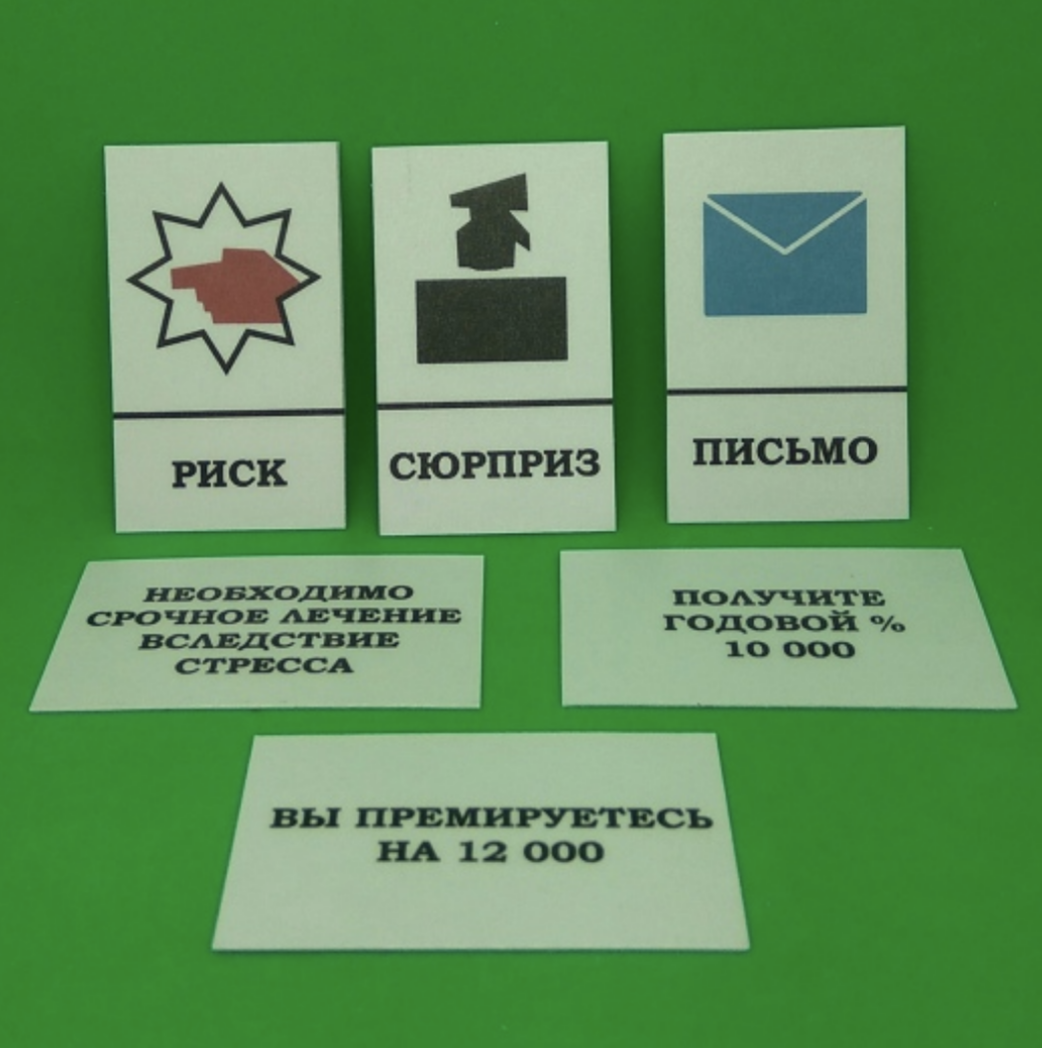

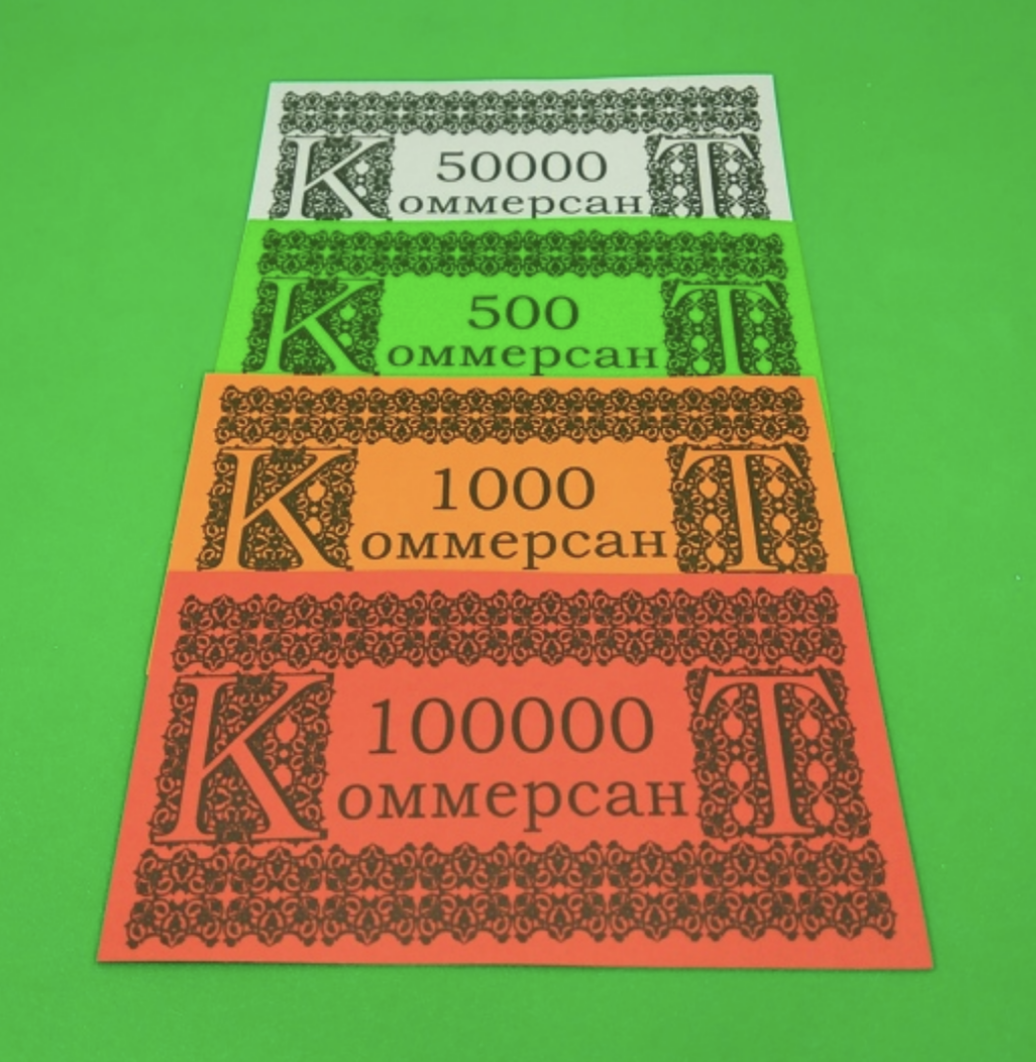

Kommersant functions as a variant of Monopoly (1935), with players investing in property, developing businesses, and drawing cards with boni and penalties. Unlike most games in the vein of Lizzie Magie’s Landlord’s Game (1904), Kommersant splits its circular track into two concentric rings, with the inner ring representing a secondary and more significant economy for investments that must be reached in-game. Within that ring, “Theaters” and “[Distribution] Bases” stand for control over the culture industry and centralized distribution—both hallmarks of the Soviet planned economy. This “inner economy” doesn’t saddle players with “fines” (the relevant space is simply absent in the inner circle) and suggests identically vast, but more authoritative domains than those available on the outer circle.

A prominent feature in Kommersant’s epistemology is the ubiquity of the “Racketeering” space in both the outer and inner circles—meaning that, incidentally, a player is even more likely to land on it. This inclusion appears to have been motivated by a desire for historical accuracy, since racketeering in the early 1990s was rampant. It is, however, problematic in terms of procedural rhetoric, since parent purchasers of the game presumably wouldn’t want their children to learn that racketeering is foundational to economics. To overcome this tension, the game designers write: “Landing on a ‘Racketeering’ space doesn’t require enforcing the rule for ‘racketeering’ and depends entirely on the wishes of the players.” The game thus offers a fantasy of control over the represented economic systems: an actor may be caught up in the impersonal winds of fate and economy, but remains in charge. The ability to reject seemingly immutable elements of this new economic world is crucial. Giving players that agency expresses the designers’ attempt to include democratic choice in their representation of contemporary society—even if it is unlikely that anyone who owned the game actually followed the directions.