Filed Under: Topic > Capitalism > Kommersant” video game by Vladimir Kharchenko and Rada Ltd, 1991

Kommersant” video game by Vladimir Kharchenko and Rada Ltd, 1991

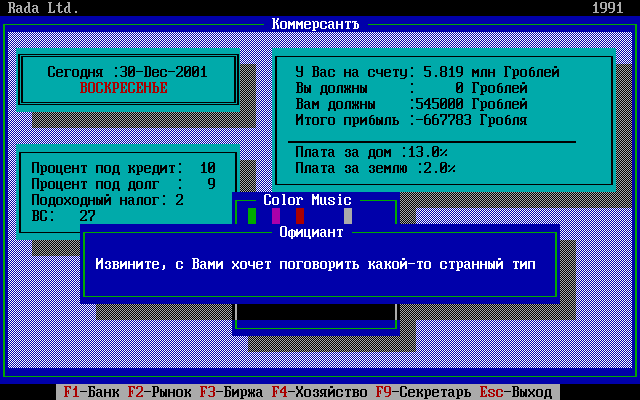

Teal boxes, clockwise from upper left: "Today: SUNDAY, 30 Dec 2001"; "Account balance: 5819 million grobles. You owe: 0 grobles. You are owed: 545000 grobles. Profit: 667783 grobles. House payment: 13.0%. Land tax: 2.0%"; "Interest rate on loan: 10%. Interest rate on debt: 9%. Income tax: 2%. VS: 27%."

Blue box: "Waiter: 'Excuse me, some weird guy wants to speak with you.'"

At bottom of screen: "F1 - Bank; F2 - Market; F3 - Stock market; F4 - Domestic economy; F9 - Secretary; Esc- Exit"

Blue box: "Waiter: 'Excuse me, some weird guy wants to speak with you.'"

At bottom of screen: "F1 - Bank; F2 - Market; F3 - Stock market; F4 - Domestic economy; F9 - Secretary; Esc- Exit"

Kommersant” is a fascinating Ukrainian political and economic computer game by a single developer, the poet Vladimir Kharchenko. It builds on the interface design of fantasy games like Oubliette (1986), where the player guided a party of adventurers through a fantasy dungeon—except that in the case of Kommersant”, the player was meant to guide a businessman through early 2000s capitalism as imagined in 1991. Set one decade in the future, in a world defined by a triumphant capitalism beset by oil crises and currency collapses, Kommersant” straddles the line between fantasy roleplay and earnest efforts at economic epistemology.

The game is unusually real-time, with events and stock prices changing continuously and forcing the player to adjust on the fly. Oubliette, by contrast, was entirely turn-based, encouraging the player to pause and think before locking in a decision. In Kommersant”, meanwhile, decisions are always panicked. Game events—currency crises, oil crises, police raids, criminal shakedowns, opportunities for criminality, and other signal elements of the perestroika era—are here imagined as normalized features of the 2000s. The result is a tense environment of financial speculation and illegal dealings. The few communities that still play Kommersant” online via emulators often create narratives by passing around a single save, with each player controlling the avatar for one year. This strategy complicates or improves the avatar’s lot, and, by extension, enriches the collective narrative.

In the original game, the player was to manipulate two currencies, money and fuel, with both treated as commodities for trade and speculation, on the one hand, and actual “things-in-the-world,” on the other. In the game, money can be physically lost, while running out of fuel can lead to the player freezing to death in their own home. The survival aspects of Kommersant” are particularly novel, while the shift of ludic economics to real-world problems makes the game an unusual commentary on the hopes and ambitions of the early post-Soviet 1990s.

The precarity of the player avatar’s survival is undercut by games within games: it is entirely possible to gamble away your fortune at the casino and horse-races that the game makes available, seeking out ruin via a spectacle of frenzied consumption. Overall, Kommersant” combines 1980s- and early-1990s-era representations of fast-paced capitalist luxury with signs of precarity, risk, violence, and volatility. The outcome is both engaging gameplay and a cutting ludic epistemology of 1990s-era economics. Notably, Vladimir Kharchenko, the creator of Kommersant”, is much better known as a video artist and poet who received several prizes for his artistic work. The game itself was distributed almost entirely for free through early 1990s pirate networks like FIDO. It is still available as freeware online here.