Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Love is Cruel, It Can Make You Fall for An Asshole

Love is Cruel, It Can Make You Fall for An Asshole

[3 items]

GRIMACES OF OUR LIFE

Love is cruel—you might even fall for a goat

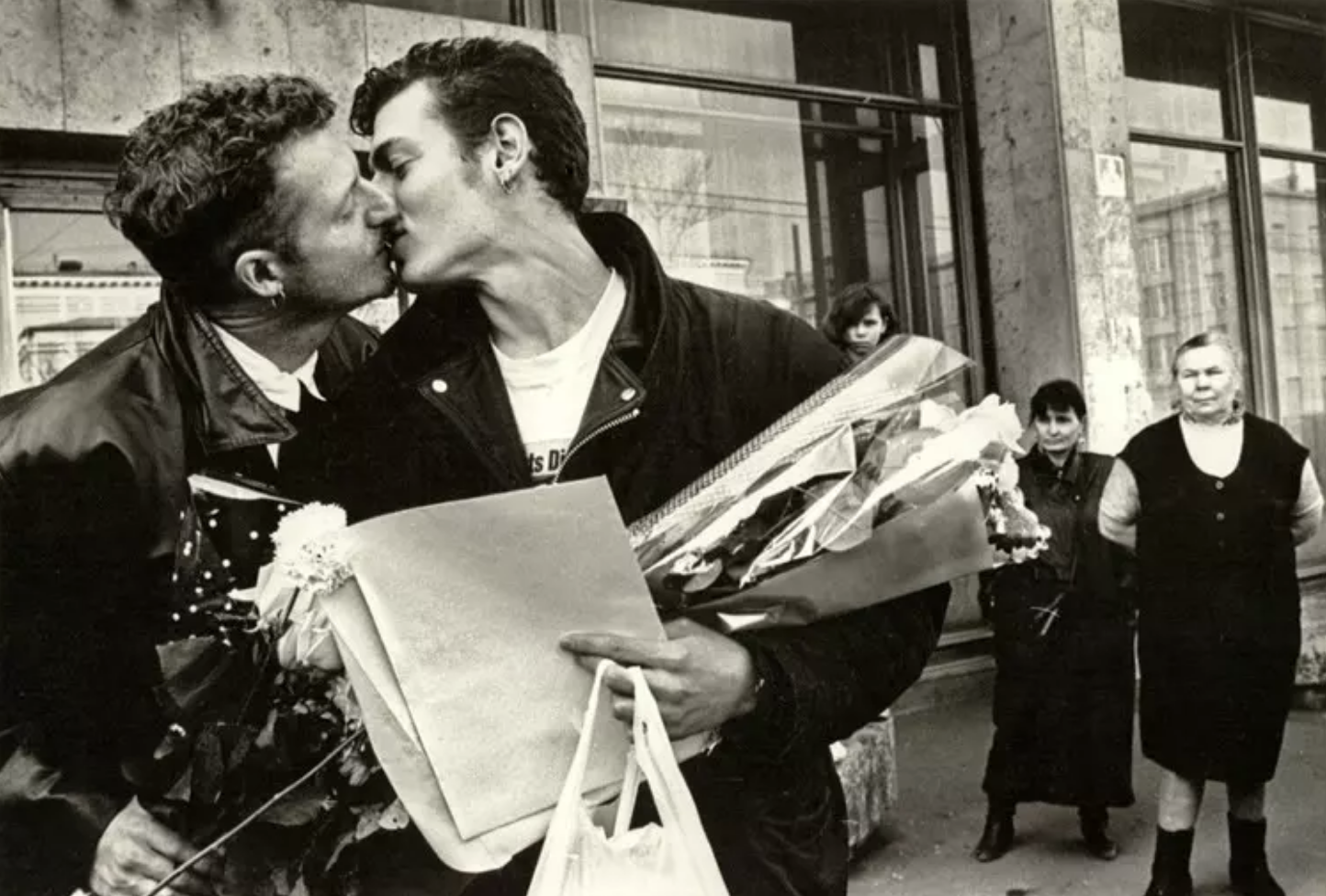

In the press release about their attempt to register their marriage, they wrote: "It's always difficult for the pioneers." And they timed their little wedding to coincide with Cosmonautics Day.

Russian journalist Yaroslav Mogutin and American artist Robert Filippini probably sincerely believe that registering their marriage truly constitutes an "artistic-political action" that will contribute to "strengthening Russian-American relations."

The Wedding Palace rejected their application. For now. But who knows what will become of our country if its leaders continue to silently facilitate the development of joint Russian/ foreign porn and drug businesses, deepen cooperation between criminals and officials, and support the creative endeavors of pedersasts and lesbians...

Alexei PERFILIEV.

This is a short, opinionated piece on the 1994 attempt by Russian gay activist, journalist, and professional épateur Yaroslav (“Slava”) Mogutin and his partner, American artist Robert Filippini, to register their marriage at a Moscow marriage registry office. This stunt, which neither participant expected to result in official recognition of their marriage, was instead designed to draw media attention to the plight of gays in Russia, and to the system’s homophobia.

The Pravda piece featured here is written from a decidedly establishment position. Its title is a Russian adage that equates to “love is blind,” or, literally, “love is cruel, it can make you fall for an asshole.” The word rendered in English as “asshole” is kozyol, meaning “goat” or, in Russian criminal slang, either a passive homosexual or an informer (“rat”). The Pravda piece extends the general meaning of the phrase—that love is a capricious and dangerous force that can cause a person to pursue romantic entanglements with people who will not treat them well or otherwise not make them happy—to mean that, in particularly “extreme” cases, a person might do something as “bizarre” as falling in love with a person of their own sex. Another overtone is that of bestiality, since, read literally, the saying’s second clause involves falling in love with a goat. The article “Gay Dawn,” published in the monthly magazine Sovershenno sekretno (Top Secret) in 1994, refers to another reaction to this same event: “So now I guess we just sit and wait for a zoophile to show up at the marriage registry office with a frog.”

Once the official press organ of the Soviet Communist Party, since 1991 Pravda has served an equivalent function for its post-Soviet successor, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. The paper’s continued loyalty to communist ideals, and its attendant suspicion of the West, even following the collapse of the Iron Curtain, may account for the article’s disdain toward the stunt’s Russo-American dimension. Indeed, its final paragraph rehearses the Soviet-era claim that the “homosexual scourge” is fundamentally Western in origin.

Mogutin and other post-Soviet LGBTQ activists often pointed to the paradoxical, patriarchal conservatism toward sexual difference among ostensibly ultra-progressive Soviet authorities. In their view, the Soviet stance on homosexuality was at least as backward as that of the USSR’s declared arch-antagonists—the fascists. Like the historical Nazis, as well as the religious fundamentalists and ultra-conservatives in the West, Soviet discourse (and its post-Soviet remnants) framed acceptance of same-sex relationships as a sign of societal degeneracy and associated same-sex relations with obscenity, illegal drug use, and other criminal behavior. In a testament to its hateful spirit, the 1994 Pravda article, alongside the neutral “lesbians,” uses the derogatory “pederast” to refer to gay men.