Filed Under: Print > Journalism > Megapolis-Ekspress: Urban Exoticism and National Pride

Megapolis-Ekspress: Urban Exoticism and National Pride

[6 items]

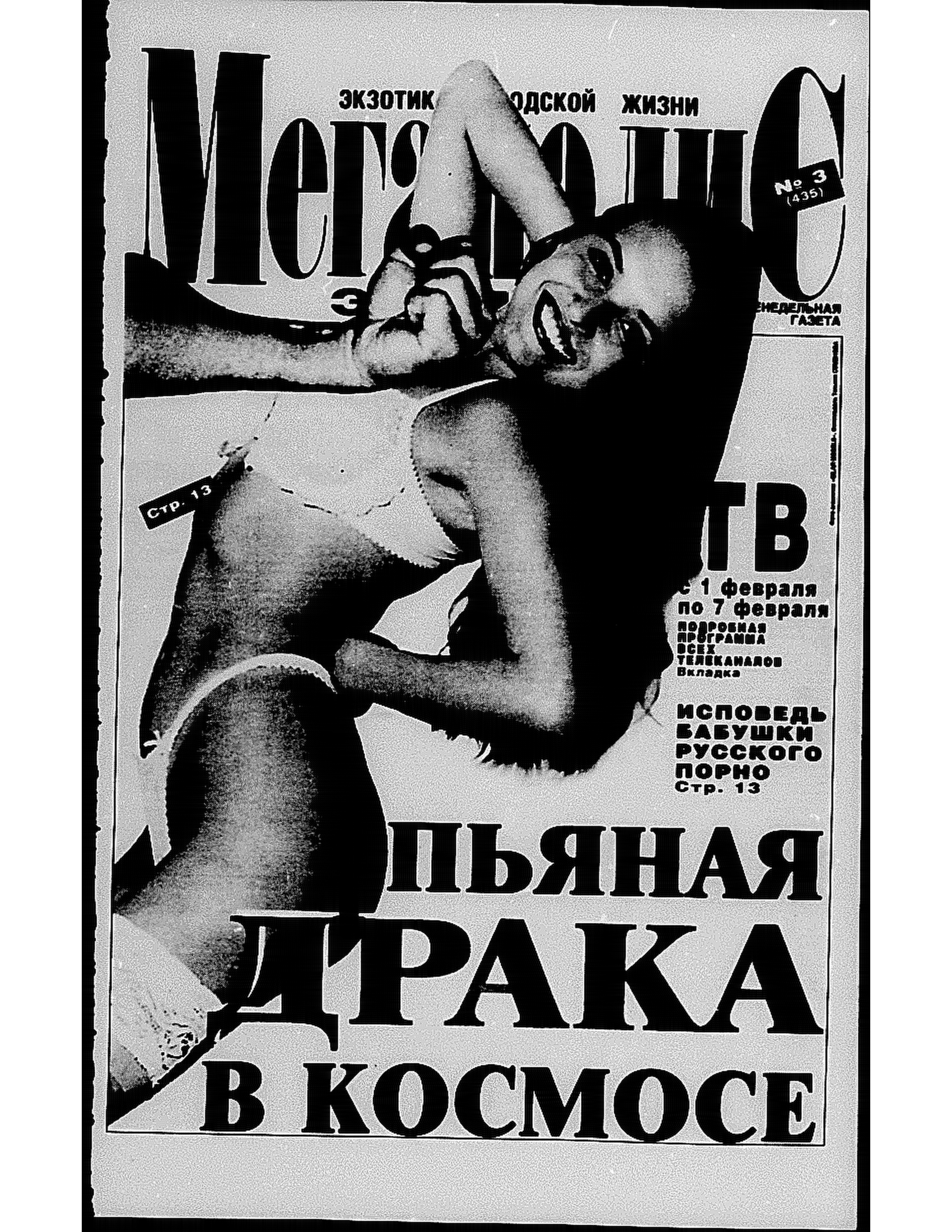

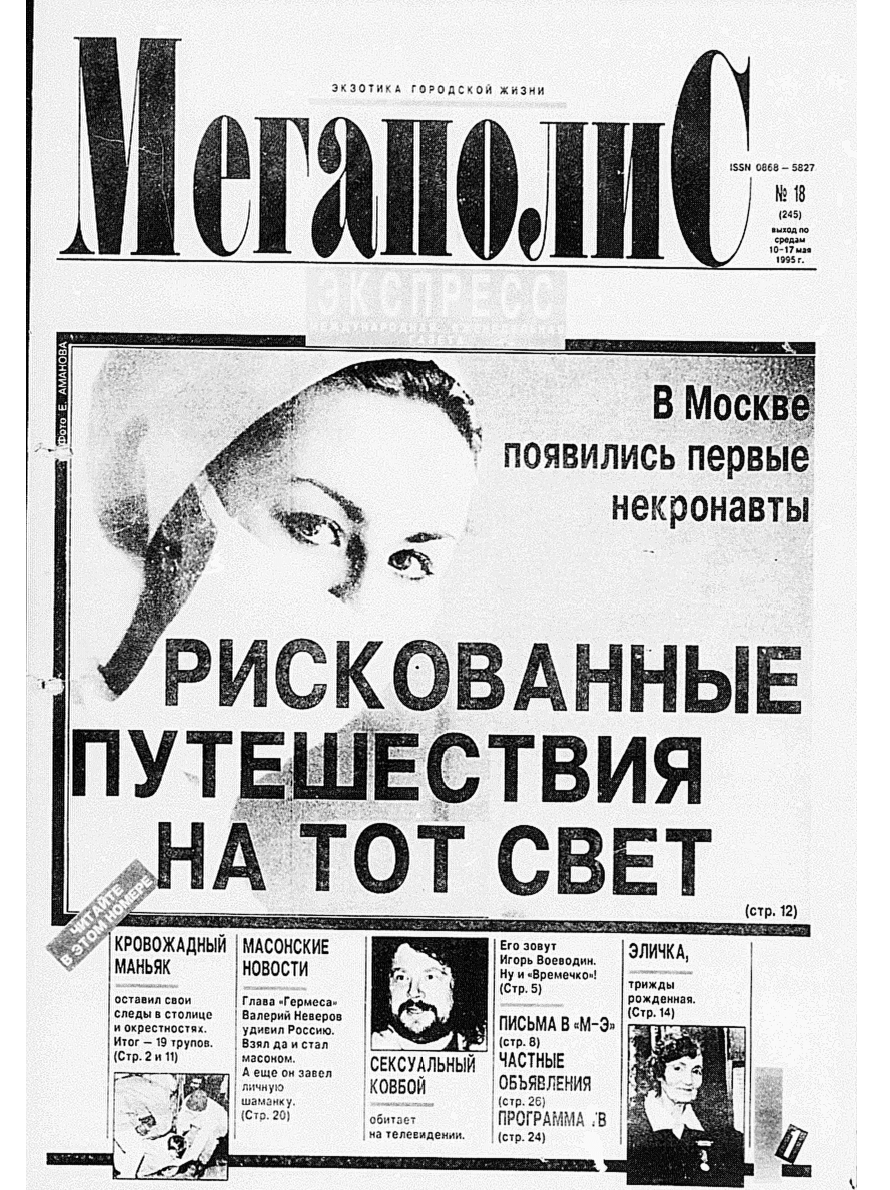

Image 1: Headline reads: "Drunken brawl in space" Image 2: Headline reads: "Santa's gone insane." Subhead: "And the Snow Maiden's pregnant." Image 3: Headline reads: "Russian scientists create a pill that allows you to earn tons of money." Image 4: Headline reads: "Save your wives from the shape-shifters!" Image 5: Headline reads: "Ten days in the witch's embrace." Subhead reads: "A visit from Nina from an unmarked grave." Image 6: Small text reads: "Moscow's first necronauts." Headline reads: "Risky travels to the afterlife."

Megapolis-ekspress, one of the most popular tabloids of the 1990s, began as a typical perestroika-era magazine on politics and society, occupying the same niche as Ogoniok and Moskovskie novosti. But in 1994, it underwent a drastic change when Igor Dudinsky took over as editor-in-chief. Under Dudinsky, who, like right-wing philosopher Alexander Dugin, was a former member of postmodern writer Yuri Mamleev’s (1913-2015) metaphysical underground circle, Megapolis-ekspress transformed into the apotheosis of Western-style tabloid sensationalism.

Per its new slogan and subheading, “the exoticism of urban life,” the magazine’s stories featured cases of (self-)cannibalism, sexual encounters with werewolves, interviews with retired “babushki of Russian porn,” travels to the afterlife, brawls in space, and accounts of Santa’s alcoholic binges and sexual escapades. Like other former members of Mamleev’s circle, Dudinsky had a taste for black magic, shamanism, witchcraft, satanism, and “mystical Nazism”—and for the absurd sadism and the gratuitous violence of Lautréamont’s Songs of Maldoror (1868-9), which had inspired the Surrealist movement in the early twentieth century. Here, an article by Dudinsky from a 1995 issue of the magazine (“Nine Days in the Arms of a Witch,” fifth image above) reflects his fascination with occultism, the afterlife, and the secret codes and surreal irony of underground culture.

Although Megapolis-ekspress was a highly lucrative enterprise (at its peak, its print runs approached 1 million copies per issue), Dudinsky justified his decision to experiment with the tabloid genre through an appeal to populist patriotism. His publication’s commercial success, he explained, freed it from financial and political pressures—in contrast with arguably more serious Russian periodicals treating politics and society, which owed their existence to various oligarchs whose interests they were bound to represent. In his view, Megapolis-ekspress provided a popular, highly accessible form of entertainment. At the same time, the objects of the magazine’s grotesque irony were capitalism, consumerism, and the decadence of “the Western way of life”—with its promises of eternal youth and instant sexual gratification—to which Russians had turned after the fall of the Soviet Union. It is in this sense, according to Dudinsky, that his tabloid represented a populist, patriotic, and—despite its imitation of Western models—anti-Western project.

Per its new slogan and subheading, “the exoticism of urban life,” the magazine’s stories featured cases of (self-)cannibalism, sexual encounters with werewolves, interviews with retired “babushki of Russian porn,” travels to the afterlife, brawls in space, and accounts of Santa’s alcoholic binges and sexual escapades. Like other former members of Mamleev’s circle, Dudinsky had a taste for black magic, shamanism, witchcraft, satanism, and “mystical Nazism”—and for the absurd sadism and the gratuitous violence of Lautréamont’s Songs of Maldoror (1868-9), which had inspired the Surrealist movement in the early twentieth century. Here, an article by Dudinsky from a 1995 issue of the magazine (“Nine Days in the Arms of a Witch,” fifth image above) reflects his fascination with occultism, the afterlife, and the secret codes and surreal irony of underground culture.

Although Megapolis-ekspress was a highly lucrative enterprise (at its peak, its print runs approached 1 million copies per issue), Dudinsky justified his decision to experiment with the tabloid genre through an appeal to populist patriotism. His publication’s commercial success, he explained, freed it from financial and political pressures—in contrast with arguably more serious Russian periodicals treating politics and society, which owed their existence to various oligarchs whose interests they were bound to represent. In his view, Megapolis-ekspress provided a popular, highly accessible form of entertainment. At the same time, the objects of the magazine’s grotesque irony were capitalism, consumerism, and the decadence of “the Western way of life”—with its promises of eternal youth and instant sexual gratification—to which Russians had turned after the fall of the Soviet Union. It is in this sense, according to Dudinsky, that his tabloid represented a populist, patriotic, and—despite its imitation of Western models—anti-Western project.