Filed Under: Topic > Free Speech > The founding of the Memorial Society in the late 1980s

The founding of the Memorial Society in the late 1980s

[3 items]

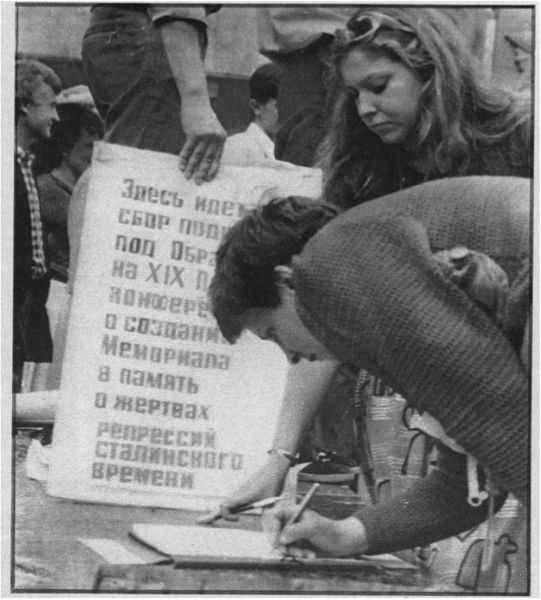

First image: Activists gather signatures for a petition demanding a monument to “victims of Stalin-era repressions” to be established in central Moscow, 1987.

Third image: A poster from a 5 March 1989 pro-Memorial demonstration in Moscow reads, “Stalinist crimes are crimes against humanity!”

The historical and documentary society Memorial began like many other perestroika-era projects: as a voluntarist effort motivated by idealism. In 1987, following an unusually well-attended meeting of the Moscow-based Democratic Perestroika club dedicated to memory of Stalinist terror, several attendees stayed behind to discuss next steps. In the words of Elena Zhemkova , a co-founder and future Executive Director of Memorial, “It became clear that, within this larger audience of 400-500, there were enough people like me who wanted something more. So, we talked and agreed that the [Stalinist] repressions were bad, and that we should all do something to ensure they don’t happen again. [And we resolved to] discuss what that ‘something’ is, to take some practical next steps.”

That same year, members of would become Memorial began gathering petitioning the Moscow city authorities for permission to establish a monument to victims of Stalinist repression (see first image above)—the future Solovetsk Stone monument in Moscow, inaugurated 30 October 1990 (see second image above). By 1989, Memorial’s activities had gathered steam: on 5 March that year, for instance, the group help a demonstration in Moscow “for the systematic de-Stalinization of Soviet society” (see third image above). Illustrious members included medievalist and gulag survivor Dmitry Likhachev and Nobel Peace Prize-winning physicist and dissident Andrei Sakharov (1921-1989). Through the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, Memorial grew in size and scope, establishing branches throughout the former Soviet bloc and carrying out expeditions, memorial efforts, and research projects.

During the period of Putin and Medvedev’s “tandemocracy” (2008-2012), however, the organization became the victim of state harassment. In 2008, police raided its St. Petersburg offices. In 2012, vandals spray painted “foreign agent” on the group’s Moscow headquarters—although it took until 2015 for the government to classify them as such officially. In 2016, the civil rights activist and historian Yury Dmitriev, head of Memorial Karelia and discoverer of a major NKVD mass execution site at Sandarmokh, was accused of disseminating child pornography, and, later, lewd acts against a minor. As of this writing in 2024, he remains in prison and is widely considered a political prisoner.

In late December 2021, Dmitriev’s prison sentence was extended to 15 years. The same day, Russia’s Supreme Court ordered the “liquidation” of Memorial, which it called a “public threat.” After being formally dismantled, Memorial and its members continued to be harassed—even as the organization won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2022. In March 2023, police raided Memorial’s Moscow offices and the homes of several leaders as part of a broader criminal case stemming from accusations that the group is “rehabilitating Nazism,” a charge carrying heavy penalties in contemporary Russia.