The Future of Crimea

[3 items]

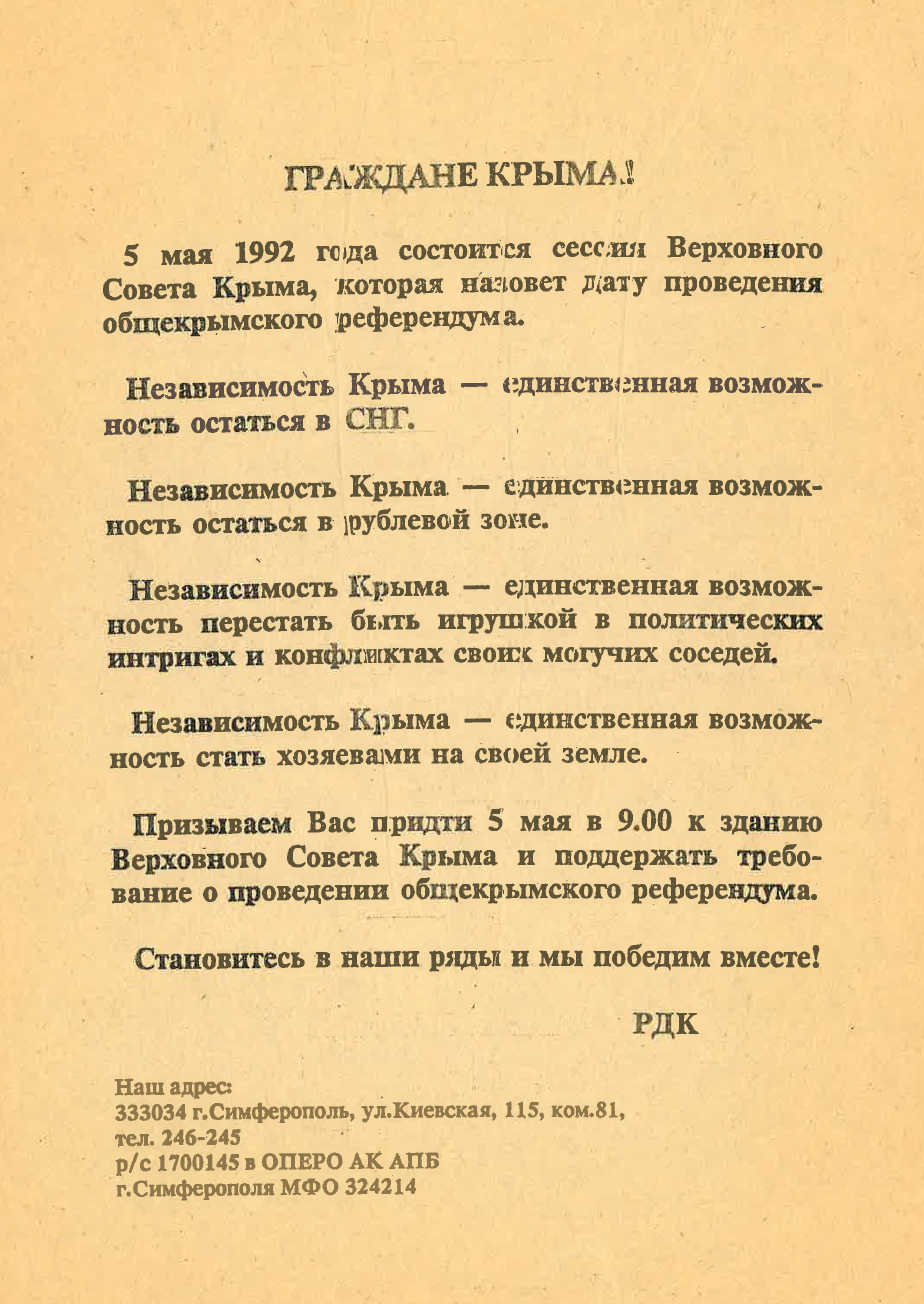

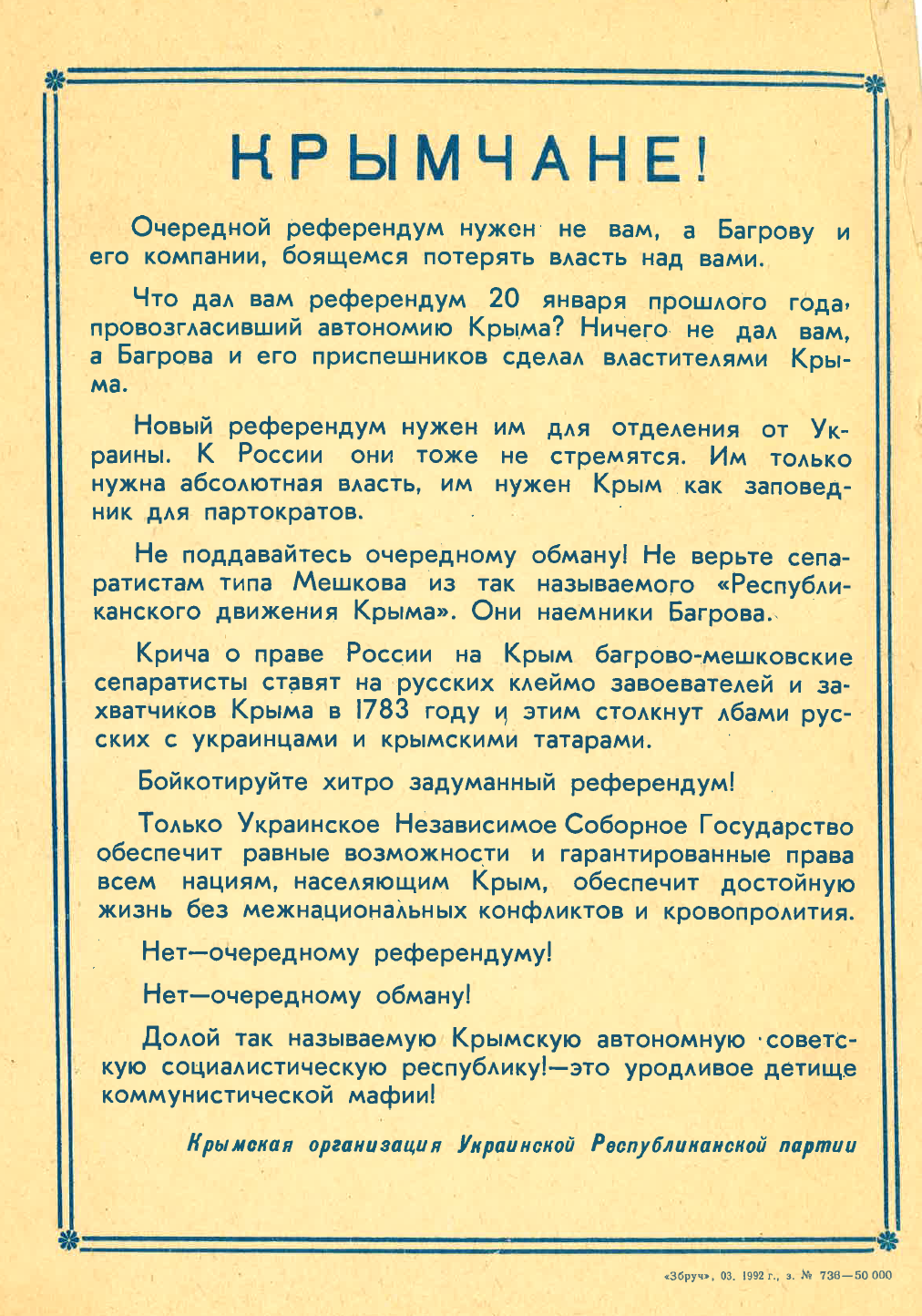

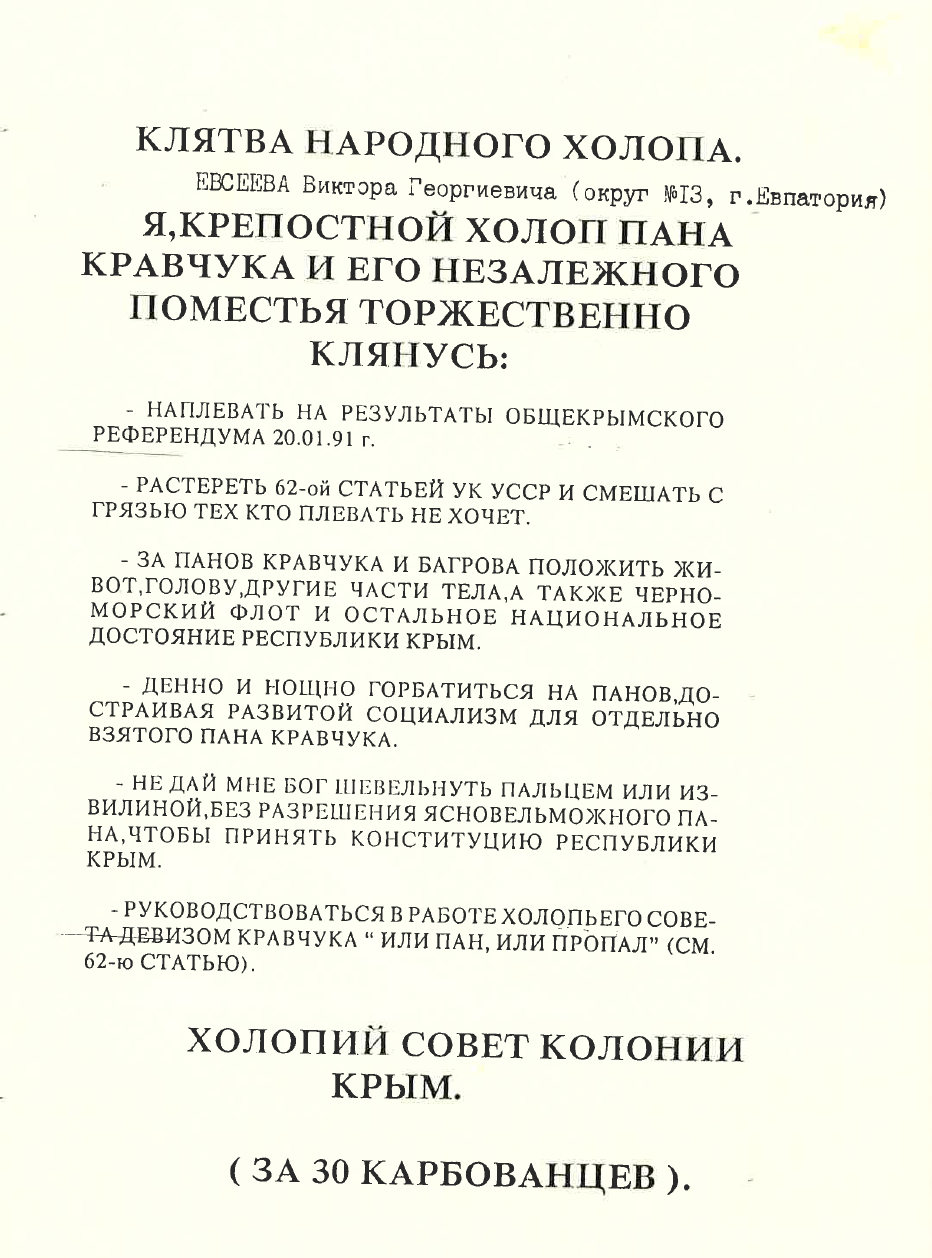

Document 1: CITIZENS OF CRIMEA! On May 5, 1992, the session of the Crimean Supreme Council will be held, where the date of the all-Crimean referendum will be announced. Crimea’s independence is the only way to remain part of the CIS. Crimea’s independence is the only way to stay within the ruble zone. Crimea’s independence is the only way to stop being a pawn in the political intrigues and conflicts of its powerful neighbors. Crimea’s independence is the only way to become masters of your own land. We urge you to come on May 5 at 9:00 AM to the building of the Supreme Council of Crimea and support the demand for an all-Crimean referendum. Join us, and together we will win! RDK [Republican Movement of Crimea] Our address: 333034, Simferopol, Kyivska St. 115, room 81 Phone: 246-245 Account: 1700145 at OPERU AK APB Simferopol, MFO 324214 Document 2: CRIMEANS! This new referendum isn’t for you; it’s for Bagrov and his cronies, who are afraid of losing their control over you. What did last year’s referendum on January 20, which declared Crimean autonomy, give you? Nothing. It only made Bagrov and his followers the rulers of Crimea. They need this new referendum to break away from Ukraine. But they aren’t looking to join Russia either. All they want is absolute power, and for Crimea to be their personal sanctuary for party elites. Don’t fall for this new deception! Don’t trust the separatists like Meshkov from the so-called "Republican Movement of Crimea." They are Bagrov’s hired lackeys. By shouting about Russia’s right to Crimea, these Bagrov-Meshkov separatists brand Russians as conquerors and invaders of Crimea since 1783, and they’ll set Russians, Ukrainians, and Crimean Tatars against one another. Boycott this cleverly devised referendum! Only an Independent, United, and Sovereign Ukrainian State can ensure equal opportunities and guaranteed rights for all nationalities living in Crimea, and provide a peaceful life without ethnic conflict and bloodshed. No to another referendum! No to another deception! Down with the so-called Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic! It’s the ugly offspring of the communist mafia! Crimean Organization of the Ukrainian Republican Party "Zbruch," March 1992, N. 736-50 Document 3: OATH OF THE PEOPLE'S LACKEY YEVSEEV Viktor Georgievich (district №13, Evpatoria) I, THE BOUND LACKEY OF MASTER KRAVCHUK AND HIS INDEPENDENT ESTATE, SOLEMNLY SWEAR: TO DISREGARD THE RESULTS OF THE ALL-CRIMEAN REFERENDUM OF 20.01.91. TO OBLITERATE ARTICLE 62 OF THE CRIMINAL CODE OF THE UKRAINIAN SSR AND DRAG THROUGH THE MUD THOSE WHO REFUSE TO DISREGARD IT. TO SACRIFICE MY LIFE, HEAD, AND OTHER BODY PARTS, AS WELL AS THE BLACK SEA FLEET AND ALL OTHER NATIONAL WEALTH OF THE REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA, FOR THE SAKE OF MASTERS KRAVCHUK AND BAGROV. TO LABOR DAY AND NIGHT FOR THE MASTERS, CONTINUING TO BUILD ADVANCED SOCIALISM FOR A SINGLE MASTER, KRAVCHUK. MAY GOD FORBID ME TO LIFT A FINGER OR EVEN A BRAIN CELL WITHOUT THE PERMISSION OF MY NOBLE MASTER IN ORDER TO ADOPT THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA. TO BE GUIDED IN MY WORK AT THE LACKEY COUNCIL BY KRAVCHUK'S MOTTO: "EITHER MASTER OR LOST" (SEE ARTICLE 62). THE LACKEY COUNCIL OF THE COLONY OF CRIMEA. (FOR 30 KARBOVANTSIV).

Before the Soviet Union ended, Crimea had already declared its independence. In a January 1991 referendum, the peninsula voted to act as an independent participant in the ongoing New Union Treaty negotiations. It became the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), led by Nikolai Bagrov, separate from the Ukrainian SSR and the Russian Federation. Had negotiations been successful and the Soviet Union saved, Crimea would have been its own autonomous subject. The fate of the Crimean ASSR was decided over a series of referenda held in 1992. The documents comprising this artifact are drawn from the surrounding debates.

One, representing the “Republican Movement of Crimea,” advocated for full independence. Another, from the “Crimean organization of the Ukrainian Republican Party,” advocated for integration into Ukraine. And the third, in biting satire, is written from the perspective of a serf or lackey swearing sardonic fealty to “Master [Leonid] Kravchuk,” independent Ukraine’s first president (1991-1994). The Republicans won the referendum, but only conditionally. The Crimean ASSR was renamed the Republic of Crimea and proclaimed self-government, but its pending constitution would have to be adopted in another referendum months later. Its independence was immediately challenged by Kyiv, leading it to amend its not-yet-approved constitution to declare itself part of Ukraine.

The peninsula’s independence raised concerns in Moscow, too, not least because it was home to the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, stationed at Sevastopol—a city that had held special federal status in the Soviet era. It reported not to the Oblast capital, Simferopol, nor to the Republican capital, Kyiv, but directly to Moscow. In April 1992, the presidents of newly independent Ukraine and Russia both signed declarations bringing the Black Sea Fleet under the Ministry of Defense in each respective country. Leonid Kravchuk’s declaration came first, on 5 April, beating Boris Yeltsin’s by only two days. A Russian-Ukrainian settlement later that year brought the Black Sea Fleet under the dual command of the two countries for a period of three years while a more permanent solution was negotiated.

By 1995, Crimea’s independence, and especially the authoritarian tendencies of its leader Yuri Meshkov, became too much for Kyiv. Elected in 1994 as President of Crimea (a position Kyiv never recognized), the pro-Russian Meshkov immediately came into conflict with the Crimean parliament. The parliament quickly downgraded his position from head of state to chief executive, and Meshkov responded by disbanding parliament and declaring sole control of the peninsula. On 17 March 1995, Ukrainian special forces entered Meshkov’s residence, detained him, and sent him to Moscow. The Crimean constitution was scrapped and Kyiv appointed Anotolii Franchuk Prime Minister of what was now the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. A new constitution was adopted in 1998.

Meanwhile, in May 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership, which recognized Ukraine’s borders and territorial integrity and Kyiv’s sovereignty over all of Crimea. The following year, the Black Sea Fleet was finally divided between Russia and Ukraine. Russia ended up with 80% of the fleet, but Ukraine still controlled the territory, leasing out the naval base at Sevastopol to Russia at a rate of $100 million a year. This treaty held until irregular Russian forces invaded in February 2014 and Moscow unilaterally annexed the peninsula the next month. Although Putin’s illegal and unprovoked annexation of Crimea came as a surprise to many observers, the peninsula’s complicated history puts both Putin’s power grab and its widespread acceptance among local residents and the international community into perspective.

Debates over Crimea’s fate had been a central element in establishing the post-Soviet world order. In this light, Putin’s invasion is not about “setting right” historical “wrongs” or bringing an “ethnically Russian” region “back” under Russian control. It is about breaking the delicate balances established in the early 1990s and contesting international borders through brutal military force.

One, representing the “Republican Movement of Crimea,” advocated for full independence. Another, from the “Crimean organization of the Ukrainian Republican Party,” advocated for integration into Ukraine. And the third, in biting satire, is written from the perspective of a serf or lackey swearing sardonic fealty to “Master [Leonid] Kravchuk,” independent Ukraine’s first president (1991-1994). The Republicans won the referendum, but only conditionally. The Crimean ASSR was renamed the Republic of Crimea and proclaimed self-government, but its pending constitution would have to be adopted in another referendum months later. Its independence was immediately challenged by Kyiv, leading it to amend its not-yet-approved constitution to declare itself part of Ukraine.

The peninsula’s independence raised concerns in Moscow, too, not least because it was home to the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, stationed at Sevastopol—a city that had held special federal status in the Soviet era. It reported not to the Oblast capital, Simferopol, nor to the Republican capital, Kyiv, but directly to Moscow. In April 1992, the presidents of newly independent Ukraine and Russia both signed declarations bringing the Black Sea Fleet under the Ministry of Defense in each respective country. Leonid Kravchuk’s declaration came first, on 5 April, beating Boris Yeltsin’s by only two days. A Russian-Ukrainian settlement later that year brought the Black Sea Fleet under the dual command of the two countries for a period of three years while a more permanent solution was negotiated.

By 1995, Crimea’s independence, and especially the authoritarian tendencies of its leader Yuri Meshkov, became too much for Kyiv. Elected in 1994 as President of Crimea (a position Kyiv never recognized), the pro-Russian Meshkov immediately came into conflict with the Crimean parliament. The parliament quickly downgraded his position from head of state to chief executive, and Meshkov responded by disbanding parliament and declaring sole control of the peninsula. On 17 March 1995, Ukrainian special forces entered Meshkov’s residence, detained him, and sent him to Moscow. The Crimean constitution was scrapped and Kyiv appointed Anotolii Franchuk Prime Minister of what was now the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. A new constitution was adopted in 1998.

Meanwhile, in May 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership, which recognized Ukraine’s borders and territorial integrity and Kyiv’s sovereignty over all of Crimea. The following year, the Black Sea Fleet was finally divided between Russia and Ukraine. Russia ended up with 80% of the fleet, but Ukraine still controlled the territory, leasing out the naval base at Sevastopol to Russia at a rate of $100 million a year. This treaty held until irregular Russian forces invaded in February 2014 and Moscow unilaterally annexed the peninsula the next month. Although Putin’s illegal and unprovoked annexation of Crimea came as a surprise to many observers, the peninsula’s complicated history puts both Putin’s power grab and its widespread acceptance among local residents and the international community into perspective.

Debates over Crimea’s fate had been a central element in establishing the post-Soviet world order. In this light, Putin’s invasion is not about “setting right” historical “wrongs” or bringing an “ethnically Russian” region “back” under Russian control. It is about breaking the delicate balances established in the early 1990s and contesting international borders through brutal military force.