Filed Under: Print > Journalism > The Unknown Diaghilev

The Unknown Diaghilev

[2 items]

The Unknown Diaghilev

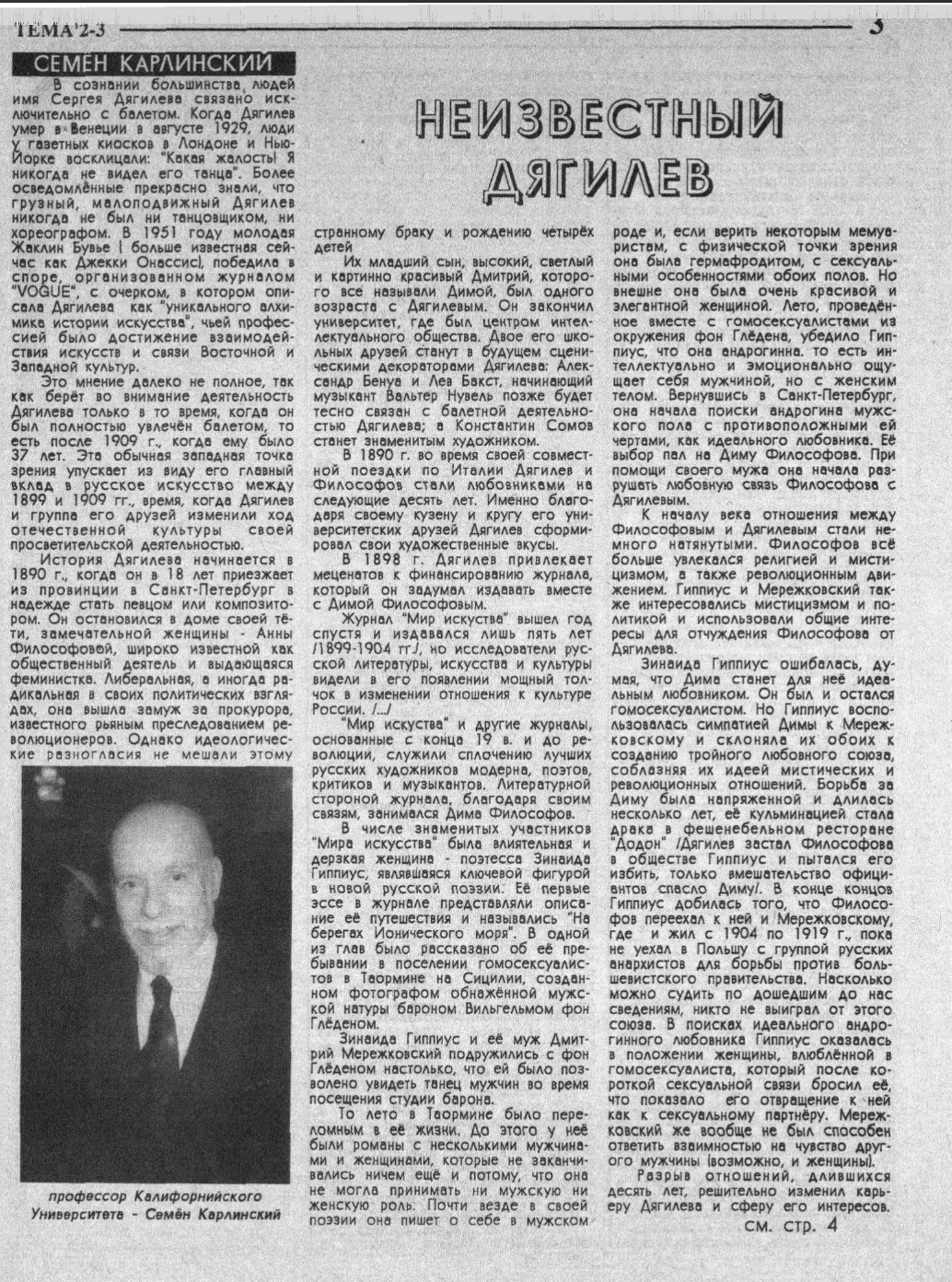

By Semyon Karlinsky, translated by Gena Stain

In the minds of most people, the name of Sergei Diaghilev is exclusively associated with ballet. When Diaghilev died in Venice in August 1929, people at newspaper kiosks in London and New York exclaimed: "What a pity! I never saw him dance!" The better informed knew perfectly well that the sickly, sedentary Diaghilev had never been either a dancer or a choreographer. In 1951, young Jacqueline Bouvier (now better known as Jacqueline Onassis) won a contest organized by "LOOK" magazine with an essay describing Diaghilev as "a unique administrator in art history," whose profession was achieving interactions between art in connection with Eastern and Western cultures.

This view is far from complete, as it only takes into account Diaghilev's activities during the time when he was completely absorbed with ballet, that is, after 1909, when he was 37 years old. This common Western perspective overlooks his major contribution to Russian art between 1899 and 1907, a time when Diaghilev and his group of friends changed the course of national culture through their educational activities.

Diaghilev's story begins in 1890, when at 18 he arrived from the provinces to St. Petersburg hoping to become a singer or composer. He stayed at the home of his aunt, a remarkable woman named Anna Filosofova, widely known as a social activist and outstanding feminist. Liberal and sometimes radical in her political views, she had married a prosecutor known for his new persecution of revolutionaries. However, ideological differences did not interfere with this strange marriage and the birth of four children.

Their youngest son, tall, fair, and strikingly handsome Dmitry, whom everyone called Dima, was the same age as Diaghilev. He graduated from university, where he was the center of intellectual society. Two of his school friends would later become stage decorators for Diaghilev: Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst; the aspiring musician Walter Nouvel would later be closely connected with Diaghilev's ballet activities; and Konstantin Somov would become a famous artist.

In 1890, during their joint student trip to Italy, Dima Filosofov became lovers for the next ten years. It was thanks to his cousin and his circle of university friends that Diaghilev formed his artistic tastes.

In 1899, Diaghilev attracted patrons to finance a magazine, which he planned to publish together with Dima Filosofov.

The magazine "Mir Iskusstva" (World of Art) was published a year later and was published for only five years (1899-1904). According to research on Russian literature, art, and culture, its appearance marked a turning point in changing attitudes toward Russian culture. "Mir Iskusstva" and other magazines founded from the late 19th century until the revolution served to unite the best Russian modern artists, poets, critics, and musicians. The literary side of the magazine, thanks to his connections, was managed by Dima Filosofov.

Among the famous participants of "Mir Iskusstva" was a woman with a long career – the poetess Zinaida Gippius, who was a key figure in new Russian poetry. Her writings in the magazine included descriptions of her travels entitled "On the Shores of the Ionian Sea." One chapter described her stay in a homosexual settlement in Taormina, Sicily, created by Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden, a photographer of nude male figures.

Zinaida Gippius and her husband Dmitry Merezhkovsky became so friendly with von Gloeden that she was allowed to see men dancing during a visit to the baron's studio.

That summer in Taormina was a turning point in her life. Before that, she had romances with several men and women, which were not distinctive also because she could accept neither a male nor female role. Later, in her poetry, she wrote about herself in the masculine gender, and, if we are to believe some memoirists, from a physical point of view she was a hermaphrodite, with sexual characteristics of both sexes. Outwardly, she was a very beautiful and elegant woman. The summer spent in the homosexual environment of von Gloeden convinced Gippius that she emotionally, intellectually, and emotionally felt herself to be a man, but with a female body. Returning to St. Petersburg, she began searching for a male with opposite traits, as a feminine lover. Her choice fell on Dima Filosofov. With the help of her husband, she began to destroy Filosofov's love affair with Diaghilev.

By the beginning of the century, the relationship between Filosofov and Diaghilev had become very strained. Filosofov became increasingly interested in religion and mysticism, as well as the revolutionary movement. Gippius and Merezhkovsky were also interested in mysticism and politics and used common interests to alienate Filosofov from Diaghilev.

Zinaida Gippius was mistaken in thinking that Dima would become her ideal lover. He was and remained homosexual. Gippius, taking advantage of Dima's sympathy for Merezhkovsky, inclined them toward a union. The creation of a triple love union combined their ideas of mystical and revolutionary relationships. The struggle for Dima continued for several years, culminating in a fight at the fashionable restaurant "Donon." Diaghilev caught Filosofov in the embrace of Gippius and tried to beat him; only the intervention of waiters saved Dima. In the end, Gippius achieved her goal, and Filosofov moved in with her and Merezhkovsky, where he lived from 1904 to 1919, until he left for Poland with a group of Russian anarchists to fight against the Bolshevik government. As far as we can judge from the information that has reached us, no one benefited from this union. In search of the ideal androgynous lover, Gippius remained in the position of a woman in love with a homosexual, who, because of any sexual connection, abandoned her, not acknowledging his aversion to her as a sexual partner. Merezhkovsky was forced to reciprocate the feelings of another man (and possibly a woman).

The breakup of the relationship, which lasted ten years, decisively changed Diaghilev's career and sphere of interests.

He could no longer, as before, publish the magazine created by him and Filosofov. He also could not remain in St. Petersburg, where he constantly risked meeting the man he loved in the company of Gippius and Merezhkovsky, who had separated them. This was one of the reasons why he left St. Petersburg.

In 1908, Diaghilev met a man who became his next great love, and this meeting connected him with ballet for the rest of his life.

This man was, of course, Vaslav Nijinsky. At the time of his first meeting with Diaghilev, Nijinsky was a promising young dancer of the Imperial Ballet, distinguished by his extraordinarily high leap. As for his personal life, he was kept by a wealthy aristocrat, Prince Pavel Lvov, who paid his bills, wardrobe, and also lent him to old influential friends for the night. This was hateful to Nijinsky, but he did it because he loved Prince Lvov and was ready to do anything for him. For Lvov, however, Nijinsky was just one of his kept lovers, and he was looking for a pretext to get rid of the dancer. It was at this moment that Diaghilev appeared.

If for Prince Lvov Nijinsky was no more than an expensive toy, his love relationship with Diaghilev was an example of the finest features of ancient Greek love between teacher and student. During their five-year relationship, Diaghilev developed activities through which a little-known young dancer became a world celebrity, amazing everyone with the depth and power not only of his dance but also of his talented choreography, collaborating as an equal with the greatest stars of the stage and composers of the century—Claude Debussy, Richard Strauss, and Igor Stravinsky. Diaghilev placed Nijinsky at the very center of stunning production projects; with his participation, Nijinsky staged and danced in such ballets as "Petrushka" and "The Rite of Spring" by Stravinsky, "Afternoon of a Faun" by Debussy, "Daphnis and Chloe" by Ravel. Nijinsky danced with the greatest ballerinas of the time: Kschessinska, Pavlova, Karsavina.

They lived together for five years, and these were years of their joint artistic triumph. But then, while separated from Diaghilev, during a sea voyage to South America, Nijinsky unexpectedly proposed to a young Hungarian woman whom he barely knew and with whom he had exchanged no more than a few phrases. Nijinsky's bisexuality, hidden during his relationship with Diaghilev, now manifested itself. Diaghilev felt abandoned when he learned of Nijinsky's marriage. This was a repetition of the case with Filosofov, when a woman once again crossed his path and took away his lover. But he still loved Nijinsky, and when two years later they met in New York, where Nijinsky had come with his wife and daughter, Diaghilev met them with flowers.

Having found a new lover in the person of Leonid Massine, Diaghilev was ready to forgive Nijinsky and invited him to continue collaborating. But he did not appreciate Romola Nijinsky. The absolutely impractical Nijinsky entrusted his career to his wife. And she demanded that Diaghilev pay them for the time when Diaghilev and Nijinsky were lovers and shared finances, and threatened to cancel the ballet production if Nijinsky did not receive a larger fee. The situation was unbearable, and it was exacerbated by the presence in the company of two Tolstoyan religious fanatics who convinced Nijinsky that his former relationship with Diaghilev was a sin and a crime against God. This was too much for the sensitive Nijinsky, and he postponed making a decision.

The popular legend that Diaghilev exploited his lover is based on entries in Nijinsky's diary immediately after the breakup and on the vengeful memories of Romola Nijinsky, who felt acute hatred toward Diaghilev. The legend's longevity was due to both homophobia and the melodramatic tastes of society.

Leonid Massine was a 17-year-old ballet student when Diaghilev discovered him. Unlike Filosofov, who was homosexual, or the bisexual Nijinsky, Massine was heterosexual. But he was willing to become Diaghilev's lover for the sake of his career and artistic education, which, as he knew, depended on their relationship. He had no reason to regret his decision. The unknown young man that Massine had been before meeting Diaghilev became one of Europe's most famous choreographers. Seven years later, he left Diaghilev because of a relationship with a pretty English dancer.

It is interesting to note how the efforts of all three women who separated Diaghilev from his lovers turned out for them. Zinaida Gippius, having won Filosofov, came to live with a man who felt himself her prisoner and could not bring himself to touch her. Romola Pulszky, having married Nijinsky, discovered all his helplessness and was forced to take care of him for the rest of his life (for thirty years, the great dancer lived in insanity in a psychiatric hospital, where he died in 1950). Vera Clark, the English dancer who seduced Massine, was abandoned by him and withered into obscurity.

In the last decade of his life, when he was already 50 years old, Diaghilev had casual, non-committal romances with handsome young men. All these young men were unknown and artistically unformed when they appeared in his life, and each made a long and successful career in art.

Naturally, Sergei Diaghilev was a mentor and teacher who influenced many artists who were neither his lovers nor homosexuals—for example, Stravinsky or Balanchine, talented female dancers, women choreographers, and stage designers. But, as Igor Stravinsky complained, the backstage atmosphere of all Diaghilev's productions was uncompromisingly homosexual. This symbiosis of homosexuality and art irritated some. As a young man, Diaghilev sought out Tchaikovsky a few weeks before the great composer's death and became friends with him on the basis of their common sexual orientation. In the same way, he met Oscar Wilde in Paris in 1898.

Diaghilev's creative successes were largely achieved thanks to his relationships with the men he loved. "Mir Iskusstva," which cultural historians have described as a truly revolutionary event in the field of aesthetic perception of art, was the result of the love relationship between two cousins, Dmitry Filosofov and Sergei Diaghilev, who created this magazine and laid its aesthetic principles. Looking back at the dazzling age of Diaghilev's ballets before the First World War—brilliant production and costumes that amazed the Western world, great performers, excellent music—all this was created by Diaghilev for his beloved Nijinsky. In the period after the break with Nijinsky, the remarkable collaboration—Satie-Picasso-Massine in the ballet "Parade," etc.—was all created thanks to Diaghilev's relationship with Massine. Or Balanchine's ballets in the last years of Diaghilev's life, the greatness of which needs no proof, such as Stravinsky and Balanchine's "Apollo Musagète" or Prokofiev, Rouault, and Balanchine's "Prodigal Son"—were created for Diaghilev's young lovers—Serge Lifar and Anton Dolin.

Diaghilev is now very popular. However, few people know that it was precisely as an expression of love for men that this great dance and this great music appeared.

This article on modernist ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929) by the American scholar Simon Karlinsky (1925-2009) appeared in a 1992 issue of the magazine Tema (Theme). It represents the Russian LGBTQ community’s attempt to reconstruct a cultural and intellectual history shattered by the traumas of revolution, war, and repression. The magazine’s choice of Karlinsky as author, and Diaghilev as subject, reflects the ambient fascination with exponents of LGBTQ identities who had Russian roots, but self-actualized in the West.

Karlinsky was born in the Manchurian city of Harbin to Russian parents who had fled there after the Bolshevik Revolution. His interests in music and literature took Karlinsky from Harbin first to Western Europe, then to the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures from 1964 until his death in 2009. His controversial 1976 monograph, The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol, explored repressed homoerotic desire as a powerful force in Gogol’s oeuvre. He also wrote monographs on the famously sexually fluid Russian poets Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941) and Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945). For the publishers of Tema, Karlinsky exemplified the openly gay Russian intellectual who achieved prominence in the Western academy through scholarship centered on the influence of homosexual, sexually fluid, and/or gender fluid Russian cultural figures.

Karlinsky’s subject, Sergei Diaghilev, is remembered primarily for his work in early twentieth-century ballet. As the artistic director behind the famous Ballets Russes touring company, Diaghilev exerted enormous influence on twentieth-century dance on both sides of the Atlantic. Diaghilev was openly gay. His romantic relationships with prominent cultural figures — including art and literature critic and publisher Dmitri Filosofov (Diaghilev’s cousin), dancer Vaclav Nizhinsky, and choreographer Leonide Massine—were public knowledge. So formidable was his impact on the world of dance that heterosexual artists like Massine are said to have entered into romantic relationships with him in order to become his protégés.

Karlinsky’s article goes as far as to assert Diaghilev’s homosexual desire as a formative influence on the twentieth-century balletic canon. Diaghilev, who spent much of his life abroad and died in Venice in 1929, twelve years after the Bolshevik Revolution, here becomes an index of a cosmopolitan prerevolutionary émigré milieu where homosexual relationships occurred in plain sight. For Karlinsky, he also represents a productive Russia-West cultural encounter in which an avowedly gay impresario became a cultural ambassador from Russia to the West. It is difficult to assess the precise effect the Tema article would have had on the early-’90s LGBTQ Russian reader. Would they have felt a sense of pride and identity with Diaghilev and Karlinsky? Or would their reactions have been more complex? For someone seeking to reconnect with Russia’s suppressed LGBTQ legacy, this account of the life and loves of Diaghilev, who spent most of his career in the West, delivered by Karlinsky, a gay scholar of Russian literature and culture, born in Manchuria and writing from his well-established seat in American academe, may have evoked a compounded sense of displacement.